“Generative A.I. took over my life. For one week, it told me what to eat, what to wear and what to do with my kids. It chose my haircut and what color to paint my office. It told my husband that it was OK to go golfing, in a lovey-dovey text that he immediately knew I had not written.” This is the opening of “I Took a ‘Decision Holiday’ and Put A.I. in Charge of My Life,” from a recent article in the “Business” section of the New York Times[i]. The author, Kashmir Hill, is a working mom with a husband and two young daughters. She decided to conduct an experiment by engaging more than 20 different A.I. bots to get advice on more than 100 decisions she faced in a week. Here are some highlights:

- After giving one chatbot details about her family, it gave her not only a detailed menu plan for the week but also a shopping list for everything she would need in a matter of seconds. As she prepared meals, she could ask for cooking advice, like how to poach an egg. The bot’s voice was casual, warm, friendly and patient.

- She was given a daily schedule for her week that balanced work, personal care, and family time.

- She took photos of a room she wanted to paint and color swatches at Lowe’s, then let a bot help her choose the ideal color.

- “Halfway through the week, I found myself in a J. Crew dressing room because A.I. hated my clothes. I had uploaded photos of my wardrobe to StyleDNA. Based on a scan of my face, it had determined my style and optimal color palette. Most of what I owned, including some of my favorite items, were not a good match for me, according to the A.I. stylist. The app fixated on two garments — a pair of light denim shorts and a fluorescent orange exercise shirt — encouraging me to incorporate them into almost every outfit. She tried them on and shared the recommendations with some friends. They thought she looked like a boring mannequin.

- She wrote a personal greeting and made a video recording reading of it so a bot could use her image and voice to compose new messages to friends and family, as well as social media. But when it digested one of my articles for a TikTok video, the script was wooden and some of my movements were exaggerated in a creepy way. When I used my avatar to send a loving, A.I.-composed message to my mom, she was horrified. “You seemed so phony!!! I thought you were mad at me!!” she replied.’

- She also had the bot create an invitation to her mother-in-law that didn’t go over well: “The messages A.I. composed on my behalf were overly effusive. Even when they reflected my own thoughts and desires, they came across as inauthentic to others, such as when I let A.I. craft the message to my mother-in-law letting her know she was welcome to come over to our house. “I was really delighted by your response and I felt so loved,” she told me, “and then it struck me that it might be A.I.”

At the end of the week, she concluded that the bots had been very helpful in organizing tasks, diagnosing a child’s illnesses, showing her how to clean the grout in her shower, and researching possible vacation destinations. “That efficiency allowed me to spend more time with my daughters, whom I found even more charming than usual. Their creativity and spontaneous dance performances stood in sharp contrast to algorithmic systems that, for all their wonder, often offered generic, unsurprising responses.” She said she “was happy to take back control of my life.”

My thoughts…

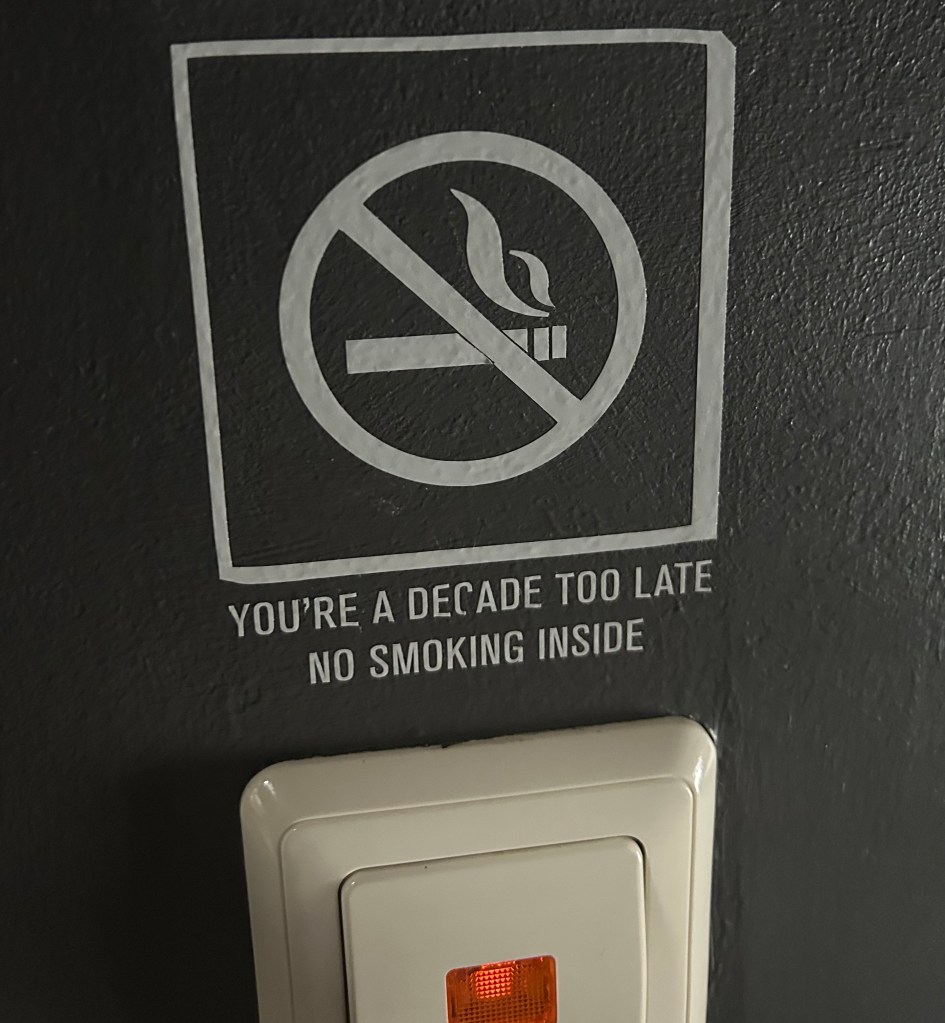

In recent years, digital devices, the internet and Smartphones have changed the way we live and learn. AI bots are accelerating this process rapidly, charming and amazing us along the way. They are being constantly refined and improved. We will be offered more and more opportunities to get what we want out of life in ways that we cannot now imagine. The author found them useful in many ways.

But if we allow ourselves to become increasing dependent on them, we are setting ourselves up for disillusionment. When the power grid goes out or when our digital systems fail or are hacked, we will be left with just each other and our own wits. Other people, including family members, are not being “improved” by technological advances day after day. They may not always act the way we want. They will make mistakes, show up late, and have ideas we don’t agree with. But they are real beings who have imagination and genuine feelings.

Human effort matters to us, and anything secretly crafted, or decided, by machines feels like a deception. Let’s treasure a handwritten note, a homemade pie, the sound of authentic human voices singing, and hand-made decorations. The coming holidays are not a time to give thanks for AI or to celebrate the birth of a bot. They are about human community and the fleeting moments of life.

[i] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/11/01/technology/generative-ai-decisions-experiment.html

Image: dreamstime.com