Over the years, I’ve grown in appreciation for the different ways artists imagine and portray traditional stories. The Advent and Christmas season is a great example. Here are a few of the works I have come to treasure over the years.

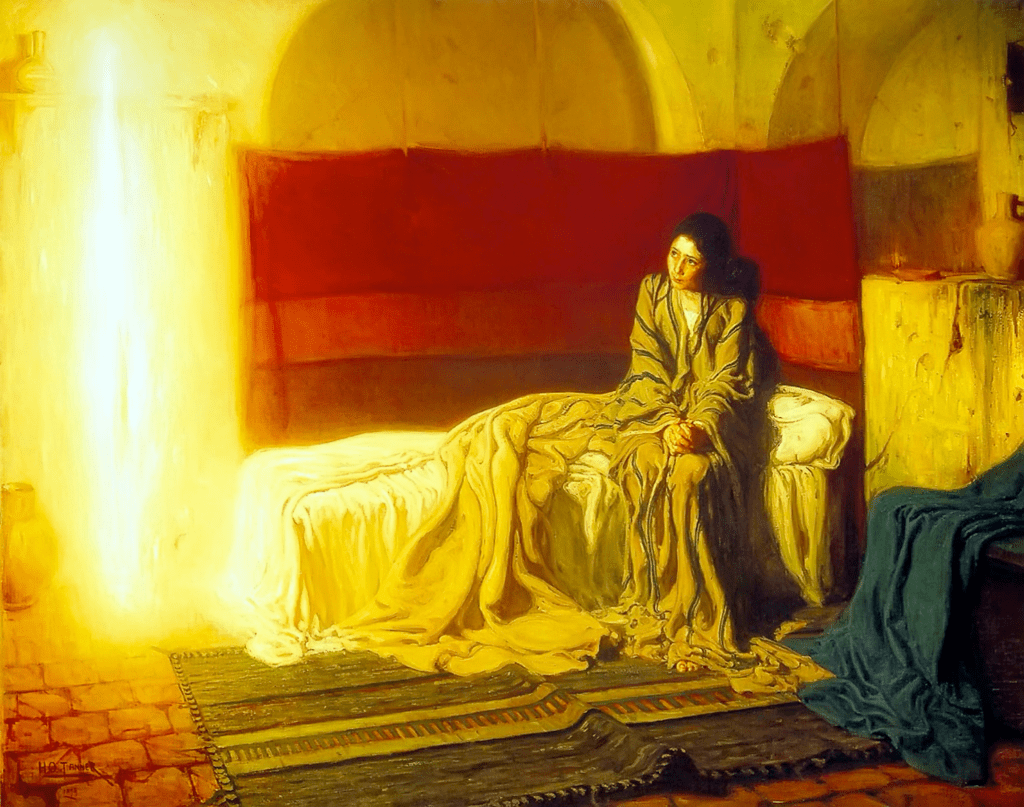

The Angel Visits Mary

A young peasant girl named Mary receives a surprise visit from the angel Gabriel, who announces she has been chosen to bear a child with a divine destiny. In 1485, Botticelli imagined it this way:

…the incoming of the divine Spirit seems to almost be knocking the angel over as it travels towards Mary.

In 1898, the English painter Tanner imagined it this way:

…the “angel” appears as a shaft of pure light; Mary seems to be contemplating what she is experiencing.

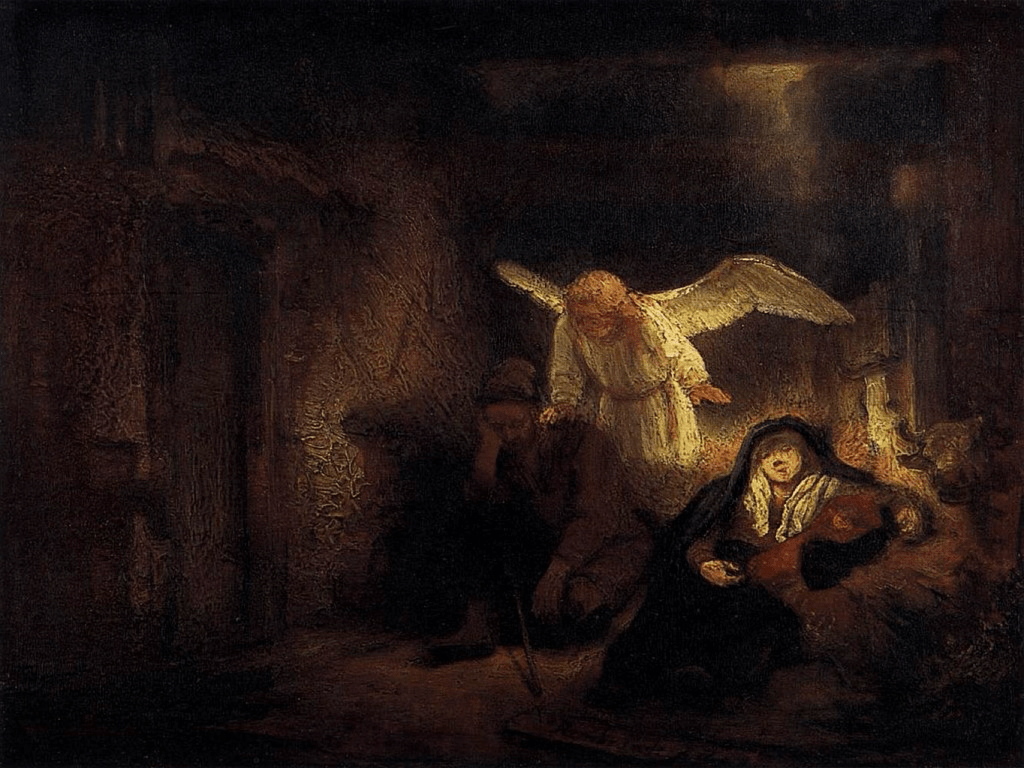

Joseph’s Dreams

Mary was engaged to Joseph, and when he discovers she is pregnant, he decides to break the engagement. But an angel appears in a dream and changes his mind.

In 1645, the French painter Georges de La Tour imagined it this way:

Joseph has fallen asleep in a chair while reading, and the unseen messenger is near him with an unseen candel illuminating the space between them as the dream is transmitted.

After the child is born, the family must flee due to threats from the government. In the process, Jospeph is twice more guided by dreams. In 1645, Rembrandt imagined one of those times this way:

…the angel is in the room with Mary and Joseph as they sleep. The angel extends the left hand to Mary while touching Joseph’s shoulder to impart the dream.

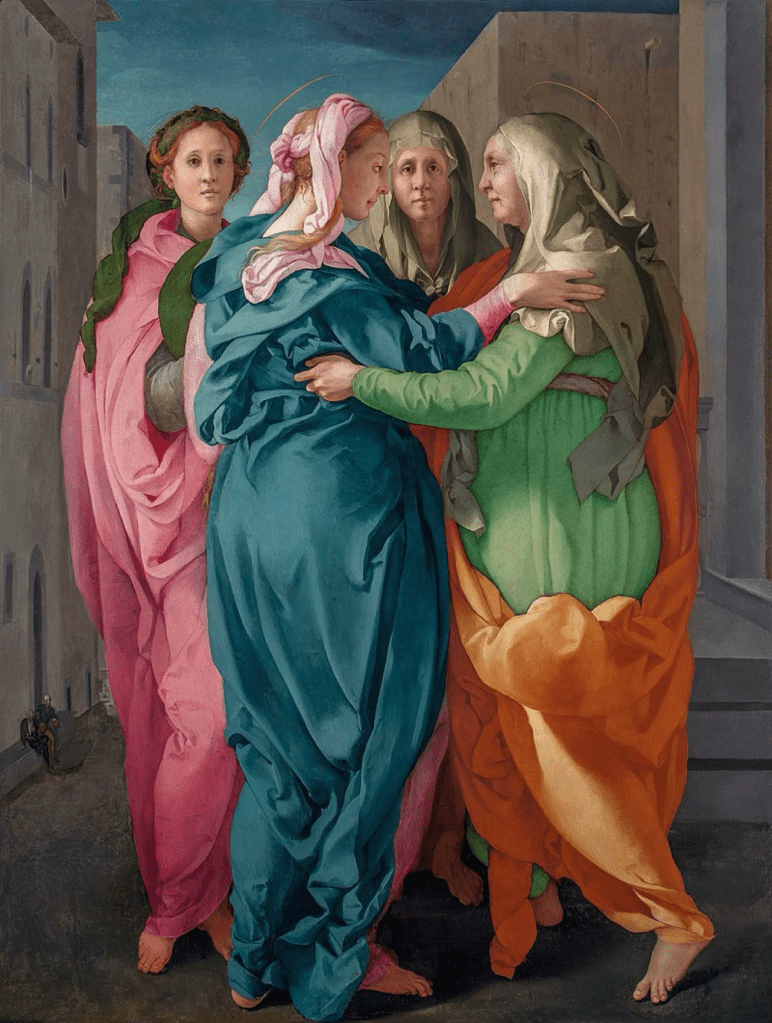

“The Visitation” — Mary Visits Her Older Cousin Elizabeth

In this episode, the newly pregnant Mary travels south to visit her older cousin Elizabeth, whom the angel Gabriel had told her has also become pregnant. When Mary arrives and greets Elizabeth, the baby in Elizabeth’s womb senses Mary’s presence and “leaps” in response; the women share an intimate moment of mutual knowing.

In 1440, the sculptor Luca Della Robia created this scene:

…here’s a close-up of the two women looking into each other’s eyes:

In 1530, the Italian painter Pontormo envisioned it this way:

…this image also merits a close-up of the faces as they behold each other:

That woman between the two of them who is looking at us — what does she want us to understand? No one knows for sure. I was excited to view this in person recently when it was at the Getty Museum a few years ago.

The Birth of the Child

In 1500, Botticelli created this scene, which he called “Mystic Nativity:”

…the manger is in the center of the picture…Joseph is asleep…Mary and the child are gazing at each other…while above, below, and around them, angels dance in celebration.

In 1646, Rembrandt created this contrasting version:

Simple, earthy, quiet, intimate.

And in 1865, the pioneering British photographer Julia Margaret Cameron created a “Nativity” scene in her studio using working class people as her models:

Great spiritual stories can contain a “surplus of meaning” – there is not just one way they can be interpreted or portrayed. Just as scientists use math to reveal important truths, artists engage our imagination. Our souls welcome this. Imagination allows us to see beyond the surface of life into the mysteries and wonder which surround us.

Merry Christmas, dear readers!

Lead image: “L’Annuncio” (The Annunciation), Salvado Dali, 1967