For centuries, a “mystic” was someone who had a rare and unique spiritual experience, different from what most of us would ever know.

This is reflected in the word itself: The term mystic is derived from the Greek noun “mystes,” which originally designated an initiate of a secret cult or mystery religion. In Classical Greece and during the Hellenistic Age, the rites of the mystery religions were largely or wholly secret. The term” mystes” is itself derived from the verb “myein” (“to close,” especially the eyes or mouth) and signified a person who kept a secret.[i]

But in recent years, the term “everyday mystic” has come into use. Here’s one description:

An “everyday mystic” is someone who seeks or experiences spiritual depth and transcendence within ordinary daily life, rather than through withdrawal from the world or extreme ascetic practices.

The concept suggests that mystical experience—that sense of connection to something greater, moments of profound awareness, or spiritual insight—doesn’t require monasteries, retreats, or renouncing worldly responsibilities. Instead, everyday mystics find the sacred in mundane activities: washing dishes, walking to work, caring for children, or sitting in traffic.[ii]

I have known quite a few “everyday mystics.” They don’t try to be different or better than anyone else — they are simply doing something they feel called to do and, in the process, find a deep connection beyond and within themselves. They don’t do it for money, or to prove their worth, or to puff up their ego.

Some examples came to my mind:

- A physical therapist who told me there were times working with patients when his mind would become quiet and he would feel as if light was passing through him to the person he was treating.

- Farmers, gardeners and hikers who sense a silent and limitless bond with the earth and the mysterious processes which underly all life.

- Musicians who feel as if the music is playing through them.

- Grandparents when they behold their grandchildren. They had loved their own children from the moment each child was born, but so much of parenting is about being a manager, behavior coach and the one person responsible for everything to do with the child. But then a grandchild appears and seeing them evokes a sense of pure wonder.

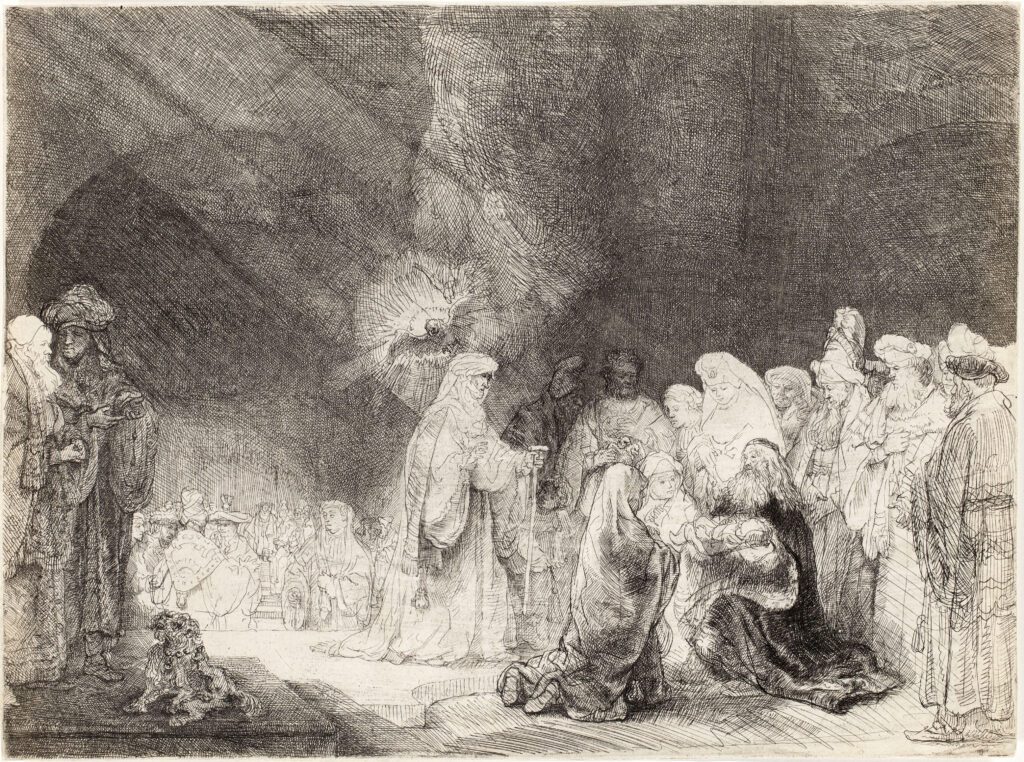

- Artists who get immersed in their process and end up creating something far beyond what they could have imagined when they started and don’t know how it happened.

- Mechanics who have an innate sense of what is wrong with a car and how to fix it with the least cost and effort, working in harmony with all the moving parts instead of simply using their will to fix something that is wrong.

- A young man who told me he was pitching for his college team and for a few innings the ball seemed to go exactly where he intended every time. The experience passed and he never had it again. He could not explain how it happened but has never forgotten what it felt like.

- Golfers who watch a ball rise and fall through the air with a grace and purpose that feels as if something more is present than a little ball being struck.

- Ocean swimmers who love the mystery of being on the surface of the limitless sea, and who feel deeply at home in salt water—perhaps sensing an unbroken thread of experience going back to our pre-human ancestors as well as our personal life as it began in the womb.

- People who know they are dying and “descend into the heart,” losing their fear and becoming open and observant towards everything around them.

Richard Rohr said, “For me, “mysticism” simply means experiential knowledge of spiritual things, as opposed to book knowledge, secondhand knowledge, or even church knowledge.”[iii]

Huston Smith said, “Most mystics do not want to read religious wisdom; they want to be it. A postcard of a beautiful lake is not a beautiful lake, and Sufis may be defined as those who dance in the lake.”[iv]

We can always be grateful when such moments come to us.

[i] https://www.britannica.com/topic/mysticism

[ii] https://claude.ai/chat/468625b2-74aa-4984-ba6e-8eb7f17a257a

[iii] https://cac.org/daily-meditations/sidewalk-spirituality/

[iv] Huston Smith, Jeffery Paine (2012). “The Huston Smith Reader,” p.93, Univ of California Press

Lead Image: “Ocean Swimmer In Thick Fog Near Reykjaice,” storyblocks.com