Fr. Virgil Cordano was a legend here in Santa Barbara. He served as priest at the Mission for more than 50 years and was loved by people all over town for his warmth, wit, intelligence and community leadership. People would ask him if wanted to be Pope. “I would for 15 minutes,” he’d say. “I’d make all the changes that need to be made, then resign. That job is too difficult.”

On May 8, we heard the announcement that the job was offered to Bob Prevost from the south side of Chicago. He accepted and is now Pope Leo XIV,

There’s a lot to like about Bob.

Places a Premium on Friendship As a young man, he chose the small Augustinian order. “Being an Augustinian means being pretty open,” Father Moral Antón said, adding that, compared to other orders, theirs does not have “very rigid norms.” “It’s about eternal friendship, friends, wanting to walk with friends and find truth with friends,” he said. “Wanting to live in the world, to live life — but with friends, with people who love you, with whom you love…It is not always something you find,” he added, “but, well, that’s the ideal.”[i]

Does His Own Dishes: When he was a bishop in Chicago, he’d drop by the priests’ residence for dinner. When the meal was done, he would take his own dishes to the kitchen to wash them. He continued that practice even when he was a cardinal in Rome. “As a cardinal, he continued to live in an apartment near the Vatican by himself, forgoing the usual nuns who help. He shopped and cooked for himself, and lunched with the young priests, busing their plates.”[ii]

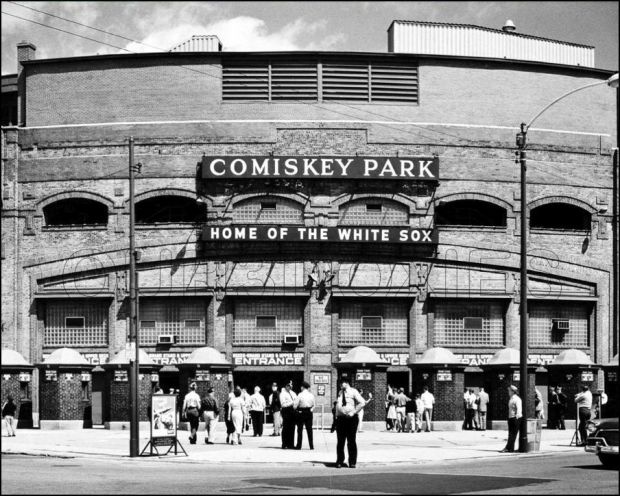

He’s a Baseball Fan. Chicago’s baseball loyalties are famously divided between the two teams that have been there since the 1800s: the Cubs on the north side, and the White Sox on the south. Bob grew up on the south side and is therefore a White Sox fan. This is not about choosing a team because you want to be associated with a winner. (Since 1917, the White Sox have won one World Series championship while the New York Yankees have won 27.) Bob is a White Sox fan because he is loyal to his neighborhood.

He Likes Road Trips He is known as someone who would turn down the option of flying to destinations in favor of driving, often by himself. “As bishop in Chiclayo, he drove 12 hours down to the capital, Lima, to meet Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin, an old friend from the United States. “I have this image of him covered with dust in a beat-up baseball cap,” Cardinal Tobin said.”[iii]

He’s a Global Citizen Bob speaks English, Italian and Spanish. He’s lived with the poor in Peru and traveled in Africa and Asia. He’s an American by birth but sees himself as serving all the people on the planet.

He Has the Courage to Face Complicated Issues Bob’s predecessor and friend, Pope Francis, took a leadership role focused on the challenge of climate change; he listened to experts from many disciplines and produced a terrific ecological encyclical, Laudato Si. Pope Leo IV is making a similar focus:

…. In his inagural address to the College of Cardinals, he said the church would address the risks that artificial intelligence poses to “human dignity, justice and labor.” And in his first speech to journalists, he cited the “immense potential” of A.I. while warning that it requires responsibility “to ensure that it can be used for the good of all.”

While it is far too early to say how Pope Leo will use his platform to address these concerns or whether he can have much effect, his focus on artificial intelligence shows he is a church leader who grasps the gravity of this modern issue.”[iv]

I appreciate these comments from one of his long-time colleagues: Father Banks said he texted his old boss after Francis died. “I think you’d make a great pope,” he said he wrote, “but I hope for your sake you’re not elected. The cardinal responded, Father Banks said, writing, “‘I’m an American, I can’t be elected.’” He still promptly responds to friends. The pope sometimes signs messages Leo XIV — sometimes Bob.[v]

I don’t envy all the challenges Pope Leo XIV faces. But I’m grateful the world can see a gifted, compassionate leader from America who wants to make a difference for the entire human family.

I like Bob. I wish him well.

[i] “The Small, Tight-Knit Religious Order That Molded Pope Leo XIV,” NY Times, May 13,2025

[ii] New York Times, May 9, 2025

[iii] “Long Drives and Short Homilies: How Father Bob Became Pope Leo,” NYTimes, May 17, 2025

[iv] “Top Priority for Pope Leo: Warn the World of the A.I. Threat,” NYTimes, May 15, 2025

[v] “Long Drives and Short Homilies: How Father Bob Became Pope Leo,” NYTimes, May 17, 2025

Lead image: “Then-Bishop Robert Prevost, now Pope Leo XIV, stands in floodwaters in the Chiclayo Diocese in the aftermath of heavy rains in northwestern Peru in March 2023, in this screenshot from a video by Caritas Chiclayo” (NCR screengrab/Caritas Chiclayo)