The documentary filmmaker Ken Burns was raised in a small, 2-bedroom home in Ann Arbor, Michigan. A recent article[i] describes his personal journey, which began with a traumatic childhood:

Ken was 11 and his brother, Ric, was 10, when their mother was on her deathbed. Their father, Robert Kyle Burns Jr., an anthropologist, was mentally ill.

As his mother’s cancer metastasized, Ken overheard conversations — his mother pleading with relatives, asking for someone, anyone, to take her boys in the event of her death. “I remember being scared — scared all the time,” he said.

With their mother in the hospital, the boys were left to wait at home for the inevitable. On the night of April 28, 1965, Ken went to bed with one of the worst stomachaches he had ever had — his body registering what none of the adults would speak about.

The pain disappeared suddenly. The phone rang. His mother was gone.

Following his mother’s death, his father would disappear “for hours and then days at a time” and sometimes be gone for months.

There is a saying I learned when I was at Hospice of Santa Barbara: “Pain that is not transformed is often transferred” — meaning if we don’t’ find a way to channel personal hurt and anguish into something positive, we can end up inflicting that pain on ourselves or others. In his grief and confusion, Burns found such a path:

The filmmaker remembers the exact moment when he decided what he wanted to do with his life: He had never seen his father cry — not in all the years his mother had fought an excruciating illness, not even at the funeral — until one night after her death. His family was in the living room in front of their black-and-white TV, watching a movie, and suddenly his father began weeping.

“I just understood that nothing gave him any safe harbor — nothing,” Ken Burns said, except the film, which had created the space for a bereaved widower to express the fraught emotions he had suppressed.

Burns began creating historical films that would present the past as something much more personal than just a series of facts. Through stories, letters, photographs, and music, he has been able to bring real people to life, whether the topic is baseball, music (jazz and country), war (World War 2 and Vietnam) or any other topic.

The article ends with this:

Years ago, a psychologist finally gave him an answer to the meaning of his work. “Look what you do for a living — you wake the dead,” the psychologist told him.

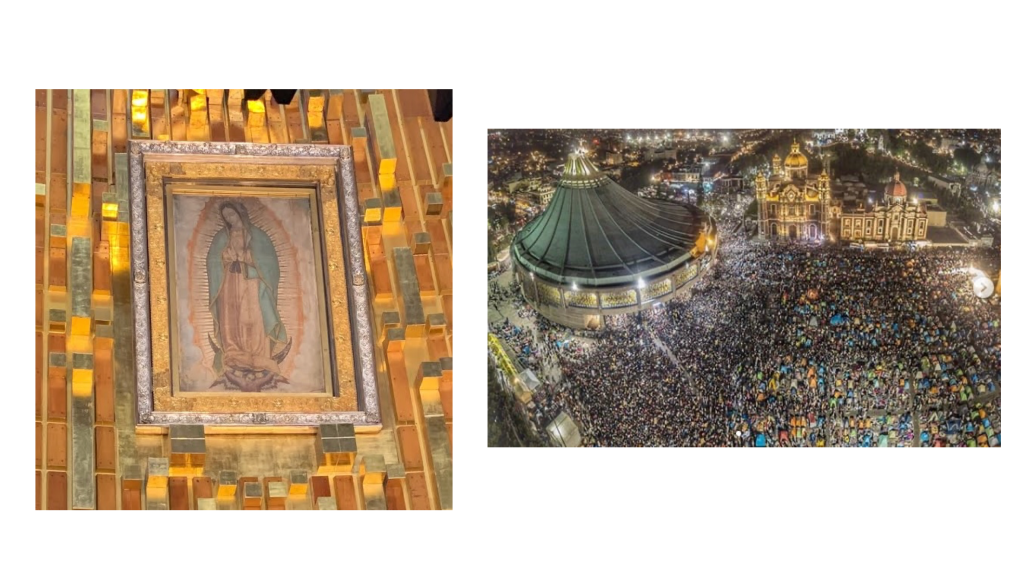

When I finished the article, I realized much of my life has been about “waking the dead.” I’ve been reading history and biographies since grammar school, constantly looking for how real people endured hardship and crises. I love listening to music that can seem to bring the composer’s lived experience accross time and directly into my heart and mind. I gaze at works of art hoping to time-travel into someone else’s world and imagination. I turn to the great spiritual traditions to listen to their wisdom and insights. I never thought of it as “waking the dead” but maybe that’s what I’m seeking – and not just to “wake” them but to be in a living and learning relationship with them.

Some years ago, I heard the writer, activist and defender of rural values Wendell Berry speak at UCSB as part of a series on environmental poets. In the question-and-answer period, someone asked if, given his dedication to family farms, gardening should be a required subject in high school. Berry paused for a minute, then said, “No, students should read Homer and the Bible, because they need to know they problems they are facing are not new.” Our world has changed a great deal in terms of technology and science, but the challenges of being a responsible and resilient human being have not. I’m grateful for those who can wake the dead so we can learn from them.

“As a baby, Ken Burns appeared in this photo showing his mother spoon feeding him.” (NY Times)

[i] “The Land That Allowed Ken Burns to Raise the Dead,” New York Times, Nov 27, 2024

Lead image: “Burns in the mid-1970s, just as he was starting to create his film studio” (from the Times article.)