I’ve been ruminating over these words for fourteen years:

Τhe nuns taught us there are two ways through life-

the way of nature… and the way of grace.

You have to choose which one you’ll follow.

Grace doesn’t try to please itself.

Accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked.

Accepts insults and injuries.

Nature only wants to please itself…

– Get others to please it too.

Likes to lord it over them…

To have its own way.

It finds reasons to be unhappy…

when all the world is shining around it,

when love is smiling through all things.

Τhey taught us that no one who loves the way of grace

ever comes to a bad end.

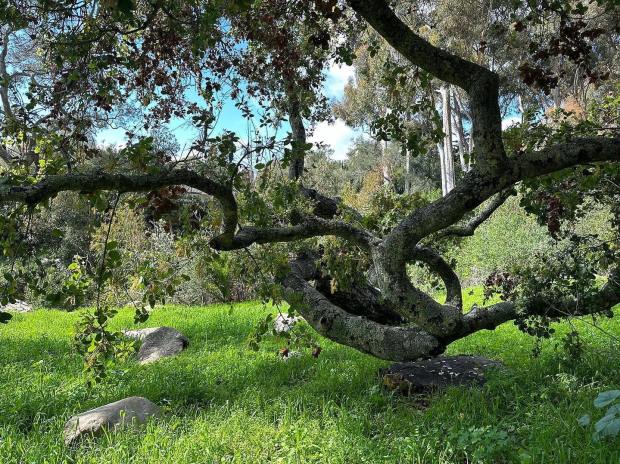

We hear this in the voice the mother of the O’Brien family (Jessica Chastain) at the opening of The Tree of Life. As she recites the first six lines, we see dream-like images of her with her young sons in 1950s suburban Texas. At the line, “Nature only wants to please itself…” the camera shifts to the father (played by Brad Pitt) at their dinner table. After several viewings, I realized the shift in focus suggests the mother embodies the grace the nuns talked about while the father embodies “the way of nature.”

“The way of grace:” self-less, tolerant, forgiving. The “way of nature:” self-centered, willful, domineering. Those living “the way of grace” experience a world shining with love; those living the way of nature are blind to all that shines, and instead “finds reasons to be unhappy.”

From the beginning of my spiritual awakening in my twenties, I wanted to “live in the way of grace.”

As a pastor, living “in the way of grace” felt like the ideal job requirement. I strived to lift that up and live that out with the people I was serving. It brought me joy.

As time has passed, I am less certain one can always live in the way of grace.

As Malick uses the phrase “way of nature,” it feels selfish, insensitive, and destructive. But we can think of it another way. I am going to interpret it as our biological and evolutionary history. We carry primal instincts within us that recognize our need to survive. We can draw on a stubborn stamina that enables us to endure hard times with grit and determination. If we lose at something and it hurts, we may resolve to recover instead of giving up. Winning and accomplishing a goal feels good. We find ourselves in a position of power and appreciate what that offers – not only for ourselves, but for others. Are these moments we want to run from?

I once organized and participated in an Earth Day retreat at the La Casa de Maria Retreat Center. We had invited a local trail guide to lead a tour of our property. He had an interest in both the natural world and ways we can listen to our ancestors. Our group took an hour to make a slow walk around the 26-acre property, stopping along the way.

We came to the organic garden and paused. He reminded us human beings have been farming for several thousand years. He asked us to close our eyes and visualize our own ancestors farming and what their life was like. Most of my ancestors came from Scandinavia. I found myself traveling back in time, watching them work in the cold climate and bare soil.

We came alongside the San Ysidro Creek. Before agriculture, our ancestors were hunters and gatherers. We closed our eyes and imagined their life. I realized my ancestors survived by learning to fish the North Sea and hunt elk. A hard life.

Living “the way of nature” involves cunning and a strong will. That can get messy when it demeans other people. But those instincts in themselves are not bad.

In 2008 I transitioned from parish work to leading nonprofit organizations. I discovered I could not be, in the eyes of everyone, always “full of grace.” Sometimes I had to make unpopular decisions. We had to let some people go, and as they left they didn’t feel like “love was smiling through all things.” But these actions had to be done. Looking back, I don’t regret them. It was part of my job.

The spiritual life is not an unending experience of grace and beauty. Jesus was more a lion than a lamb. Many of his conversations comforted, healed and renewed. But other times he confronted people with their self-righteousness, and they walked away dejected or angry. He told people what they needed to hear.

Trying to be gracious every moment doesn’t guarantee ideal outcomes. Sometimes things just go badly. But we do the best we can.

Is it true — “…there are two ways through life – the way of nature… and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you’ll follow?” I’m not so sure it’s that simple. I believe there is a third way, one which draws on both nature and grace. There are times when we need instincts for survival that nature has given us so we can protect ourselves and others and do the right thing. But that doesn’t exclude “the way of grace.” Grace is always worth striving for, and when it emerges it comes with a radiant awareness.

Images: The Tree of Life, Terrence Mallick

Last October I wrote another post inspired by Tree of Life: Where Were We?