One early spring afternoon years ago, I was making the three-hour drive on Interstate 90 from Seattle to our home in central Washington. The highway passes through Snoqualmie Pass in the Cascade Mountains. There had been plenty of snow that winter and there were only a few cars on the road as light flurries were falling. I was alone. I heard a loud crashing noise. On the right side of the road ahead of me I watched a large snow-covered branch fall to the ground from a tall pine tree . As I continued driving, I wondered how much weight it must take to break that branch off from the trunk of its tree. How many snowflakes were required to make that happen? Did just one last snowflake tip the balance?

As I continued driving, I wondered if prayers might be like snowflakes. Individually, they are virtually weightless. But can they accumulate over time to make something tangible and unexpected happen?

There have been many theories over the centuries about how prayer might actually “work.” There are many spiritual traditions encouraging people to pray. Many people share stories of how prayer has led to some remarkable outcomes.

At the same time, many people can remember times when what they prayed for did not come to be. Much has been written trying to understand “unanswered prayer.”

I have had colleagues in the medical profession recount experiences when they were working with families and individuals who were facing serious health challenges who put all their faith in prayer, sometimes to the exclusion of good science. If the malady did not disappear, the family was faced not only with the loss of a loved one but questioning their faith as well.

I no longer expect to come up with a definitive answer to what prayer is and just how it “works.” But some stories come to mind. I’m going to share one this week and more in a future posting.

When I arrived to serve my congregation in Goleta, one man who became a friend and mentor was Hank Weaver. Hank had recently retired after ten years at UCSB in the Education Abroad Program. He was a faithful Mennonite and a lifetime pacifist. Hank was a warm, engaging and brilliant man who walked with a slight limp. I soon learned his story. Just two years before, he had been diagnosed with a serious form of cancer in his lower spine. The initial prognosis indicated he might not have long to live. He decided to learn as much as he could about what he could do. He had a PhD in chemistry and, as a dedicated scientist, worked carefully with his oncologist to begin the chemotherapy.

At this time, people were beginning to use visualization as part of cancer treatment; the idea is you use your imagination in meditatation to visualize the chemo overcoming the cancer. Hank was told one common example was to imagine cancer cells as small fish swimming in your bloodstream, and the chemo is a shark eating them up one by one. Hank thought about it and said that wouldn’t work for him due to his belief in nonviolence. He developed an alternative. He imagined a catfish swimming through his bloodstream, bottom feeding on things his body no longer wanted.

Hank asked anyone who was willing to pray for his healing to do so, and many did. One particularly dedicated member (in church speak, a “prayer warrior”) told me she had created an image in her mind of Hank entering the sanctuary fully healed, and many times prayerfully held that image in her mind and soul. Hank also did all the right things in terms of diet and physical activity.

Months passed. Slowly, the cancer began to disappear. Eventually it went into remission. The damage to his spine meant that his walk would always be impaired, but that was a small price to pay for the outcome. (He did tell me one benefit of his impairment was the handicapped placard he had now had for his car – he began to get invitations from friends asking to go with him to Dodger games to take advantage of his hard-earned status for a premium parking place.)

Hank ended up self-publishing a book about his experience, Confronting the Big C. Eventually he and his wife moved to Indiana where he served as interim President of Goshen College before retiring. Hank had experienced a remarkable healing, and he believed it was the combination of good science and open-minded spirituality that led to his outcome. He lived twenty-five more years until dying at the age of 93.

I believe Hank would say there are no guaranteed outcomes in this life. None of us are getting out of here alive, and death will eventually take every one of us. But when facing serious challenges, we can choose to gather and employ all the best resources to increase our chances for a desired outcome. We may never know how all these different forces – medical, spiritual, social, emotional – might interact with each other. Some effects we can see and measure. But others, like prayer, may involve forces that are small and subtle. But that doesn’t mean they can’t make things happen.

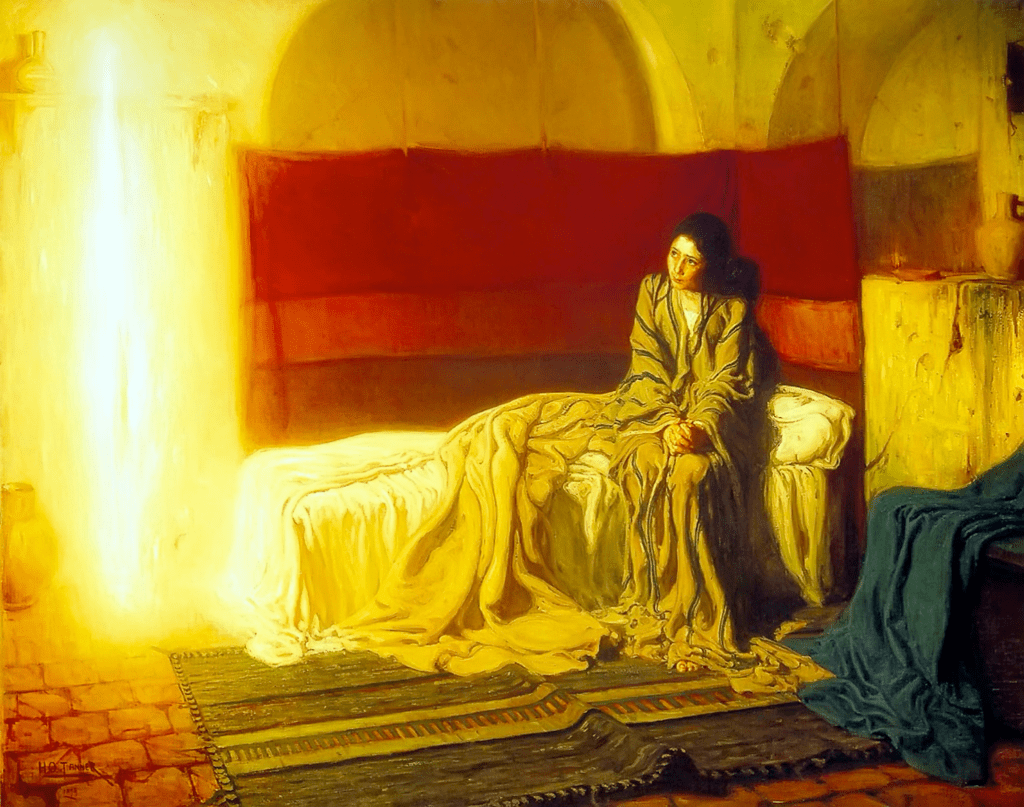

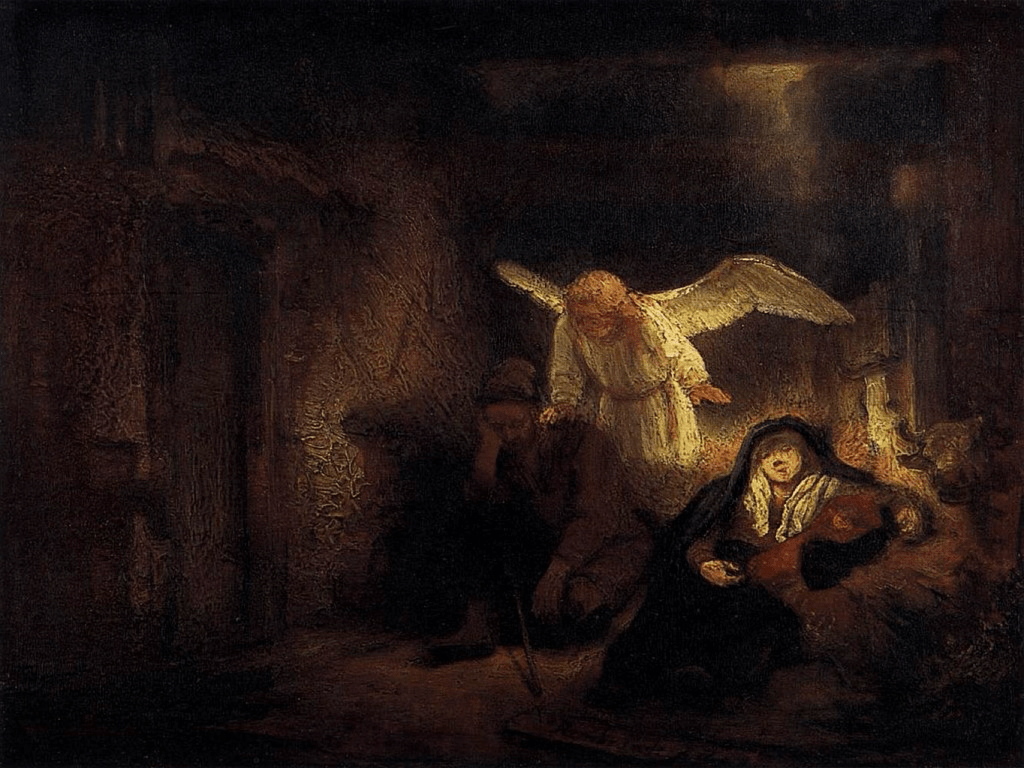

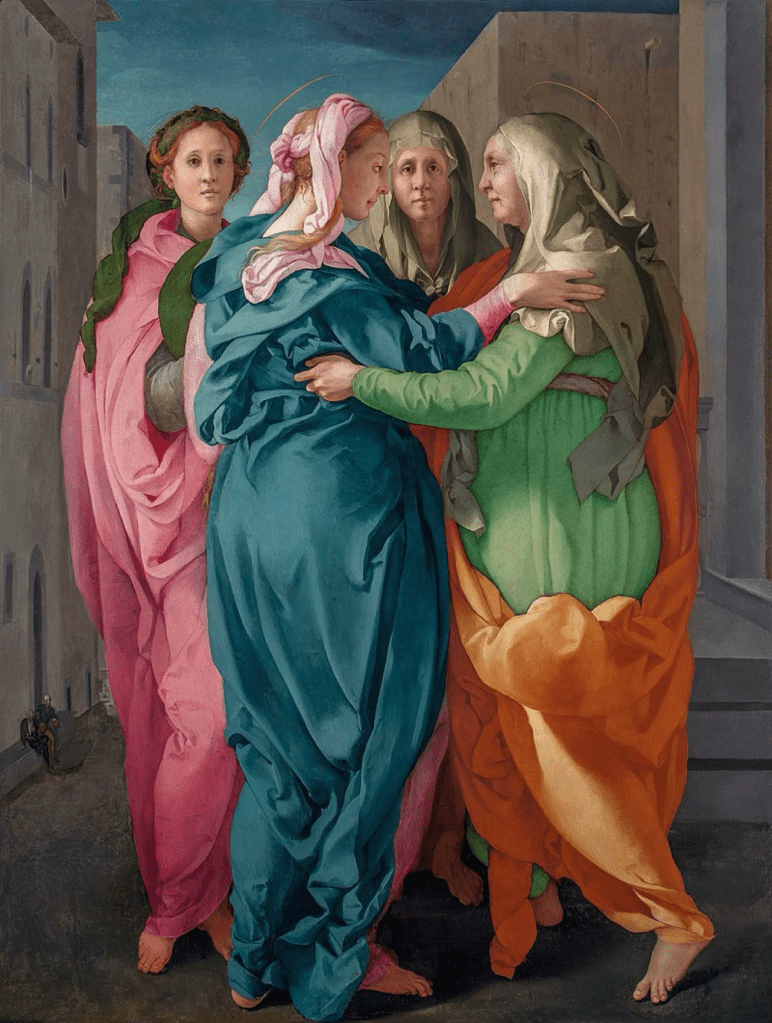

Image: Fineartamerica, Tera Fraley