Over the years, I’ve done a variety of presentations exploring the way Rembrandt portrays Biblical scenes. Time and again, I’ve been fascinated by the surprising ways he imagines and creates visual details. One example is his apparent fondness for dogs.

We can start with “The Hundred Guilder Print.” This work captures in one scene the various encounters Jesus has with a crowd of people as described in Matthew 19. Here’s the print:

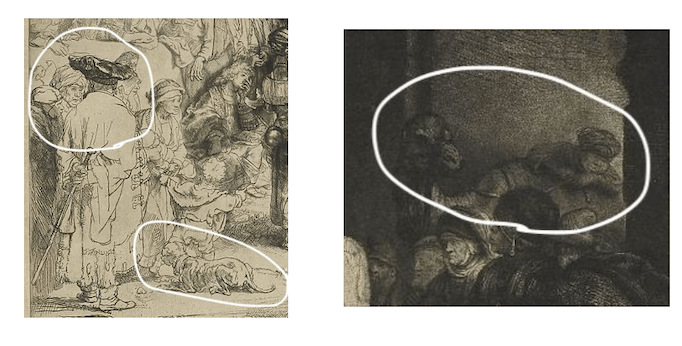

If we read the text carefully and study the scene, we see how he includes all the important characters: people who are hoping to be healed, scholars who like to debate fine points of law, mothers bringing children to receive his blessing, etc. Near the bottom left, we find something not mentioned in the text:

When I’ve seen dogs positioned like this, it is usually because they have determined they are near a spot where food scraps are likely to fall. This is certainly not mentioned in the story – it’s something Rembrandt decided to add.

Here is his portrayal of “The Good Samaritan:”

In the story, a Samaritan sees a stranger who has been beaten and robbed, and no one is stopping to help. But the Samaritan binds his wounds, puts him on his horse, takes him to an inn, and arranges for the man’s lodging and care. All that is in the story. But in the lower right corner, we see an unexpected sight:

Suffice it to say, when we see dogs in this posture, we can guess what they are doing. This is not a detail noted in any translations I am familiar with.

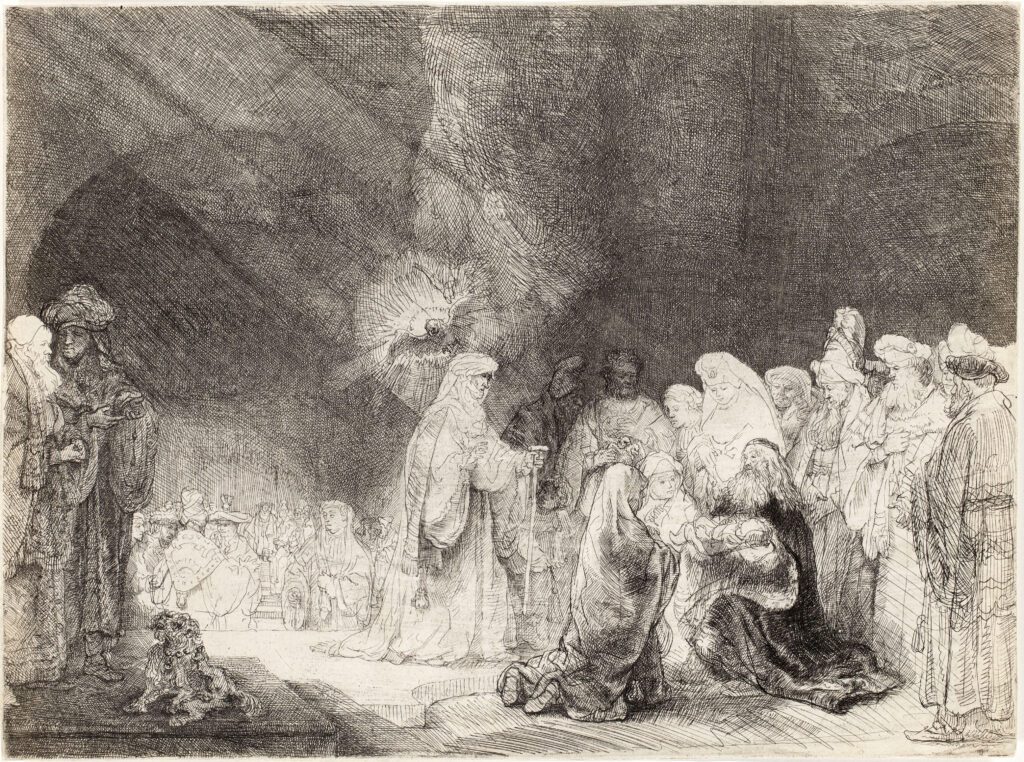

He doesn’t limit canines to outdoor scenes. In “The Presentation in the Temple,” Joseph and Mary bring their 8-day old infant to be dedicated. Two elders, Simeon and Anna, express joy upon seeing the child. Divine light streams down from the upper left highlighting the sacred moment:

And there, in the bottom left corner, we see one of our four-legged friends:

This dog is scratching his left ear with his back foot.

I have not found any articles explaining why Rembrandt inserts oridnary dogs into scenes that portray profound spiritual experiences. But my guess is he understood great spiritual moments in life don’t occur in situations where everything is perfectly staged, as if designed by Martha Stewart. They happen in nitty-gritty, down-to-earth settings where ordinary human beings experience something profound. And what is more down-to-earth than the presence of a dog in the midst of a human gathering doing what dogs do?

I have had memorable spiritual experiences in stunning cathedrals and in sanctuaries filled with glorious music. But I have also had them in hospital rooms next to bedpans and beeping monitors, dusty home building sites in the barrios of Tijuana, and while changing irrigation lines in an alfalfa field. And, like many people, I have had experiences with a dog when I feel a deep bond of knowing and caring for each other in a way that’s hard to explain. It’s all part of life, and there’s no limit to the ways and settings in which the Spirit can appear. Rembrandt shows us what that looks like.

Lead Image: “Sleeping Puppy,” Rembrandt, 1640; Victoria and Albert Museum