Last month, two long-time columnists of the New York Times, David Brooks and Thomas Friedman, were interviewed about how they are viewing the world we are living in. One of the comments caught my attention:

Friedman: … Let me start with what is a bedrock thing in my identity, and I think it’s in yours, too. For me, the two most powerful emotions driving human beings are one: humiliation and dignity. The quest for dignity and the revulsion of humiliation.That’s why I changed my business card back in 2015 from “New York Times Foreign Affairs Columnist” to “New York Times Humiliation and Dignity Columnist.” I felt that’s really what I was covering, whether it’s about China or Russia or Palestinians or anything else…”[i]

Brooks and Friedman continued discussing how this idea applied to politics, and it’s an impressive discussion. Leaving world affairs to them, I decided to see how this perspective might also illuminate everyday experiences.

I can start with something as trivial as being aware of the kind of car we drive.

Some years ago, I was invited to an event at “The Ritz-Carlton Bacara,” a 5-star luxury hotel here in Santa Barbara. I had been there before and remembered they had valet parking. I was driving a used Prius at the time, and my ego started thinking about how most other cars would be Porsches, Bentleys, Mercedes Benz and Land Rovers. I thought, “People will see my car and know I’m not a person of high status.” I decided not to care.

I thought of pets. If you have a dog or cat, the animal is not at all concerned with your social status. In their eyes, you have a full measure of dignity and deserve every ounce of their devotion. What’s not to love?

As we age, we can become disabled, dependent and frail. It’s not who we used to be, and we never thought this would be us. When we go out in public, it’s easy to feel humiliated. How meaningful it is when people interact with us in a way that recognizes our inherent dignity.

In my own career, I’ve attended many memorial services which are instructive and inspiring events. We often hear why the person being honored made a difference in the lives of others. A common theme is how they treated people – family members, employees, friends and strangers – with care and honor.

At their best, spiritual traditions affirm every person’s dignity.

In the Hebrew Bible, we read that human beings are created “in the image of God.”

Jesus was notorious for associating with people who were looked down upon – prostitutes, tax collectors, people with diseases and troubling spirits. He spoke to them with respect and broke bread with them. In those encounters, they began to release what society had said about them and instead discover their inherent worth. His form of execution was meant by Roman culture to be the ultimate display of humiliation. But instead, it became a paradoxical display of how divine love transcends the dehumanizing forces of life, conferring eternal dignity in the process.

In The Autobiography of Malcom X, the author describes his first visit as a Muslim to Mecca for the great hajj pilgrimage. Every person – no matter their race or social status in their home country– put on identical robes and joined the masses circling the Kabba and praying. After a lifetime of discrimination and humiliation as a black man in America, for the first time in his life he felt he was truly an equal: “There were tens of thousands of pilgrims, from all over the world. They were of all colors, from blue-eyed blonds to black-skinned Africans. But we were all participating in the same ritual, displaying a spirit of unity and brotherhood that my experiences in America had led me to believe never could exist between the white and non-white.”[ii] The experience changed Malcom’s life. From then on, he saw the common humanity of all people.

In human affairs, politics and everyday life, there are forces at work which are used to humiliate other people. How powerful it is to reject those forces and instead affirm the dignity of others. This is what America’s best leaders have done. This is what Dr. King stood for. This is what our spiritual traditions call us to do.

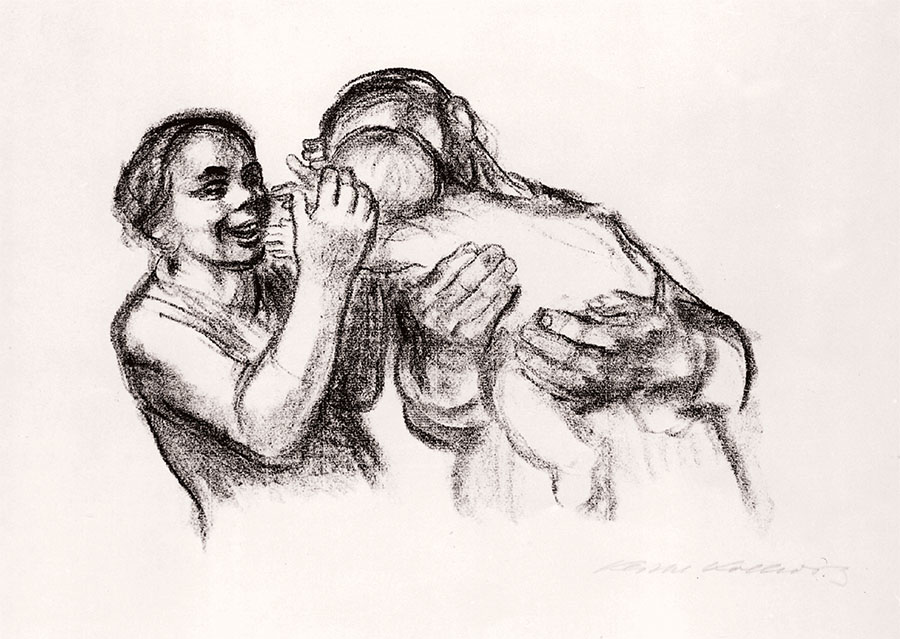

Image: “Mother and Child,” Kathe Kollwitz, Kollwitz Museum, Berlin

[i] “Thomas L. Friedman Says We’re in a New Epoch. David Brooks Has Questions. Two columnists debate this strange moment.” New York Times, Dec. 12, 2025

[ii] “Letter from Mecca,” Malcom X, April 1964; https://malcolm-x.org/docs/let_mecca.htm