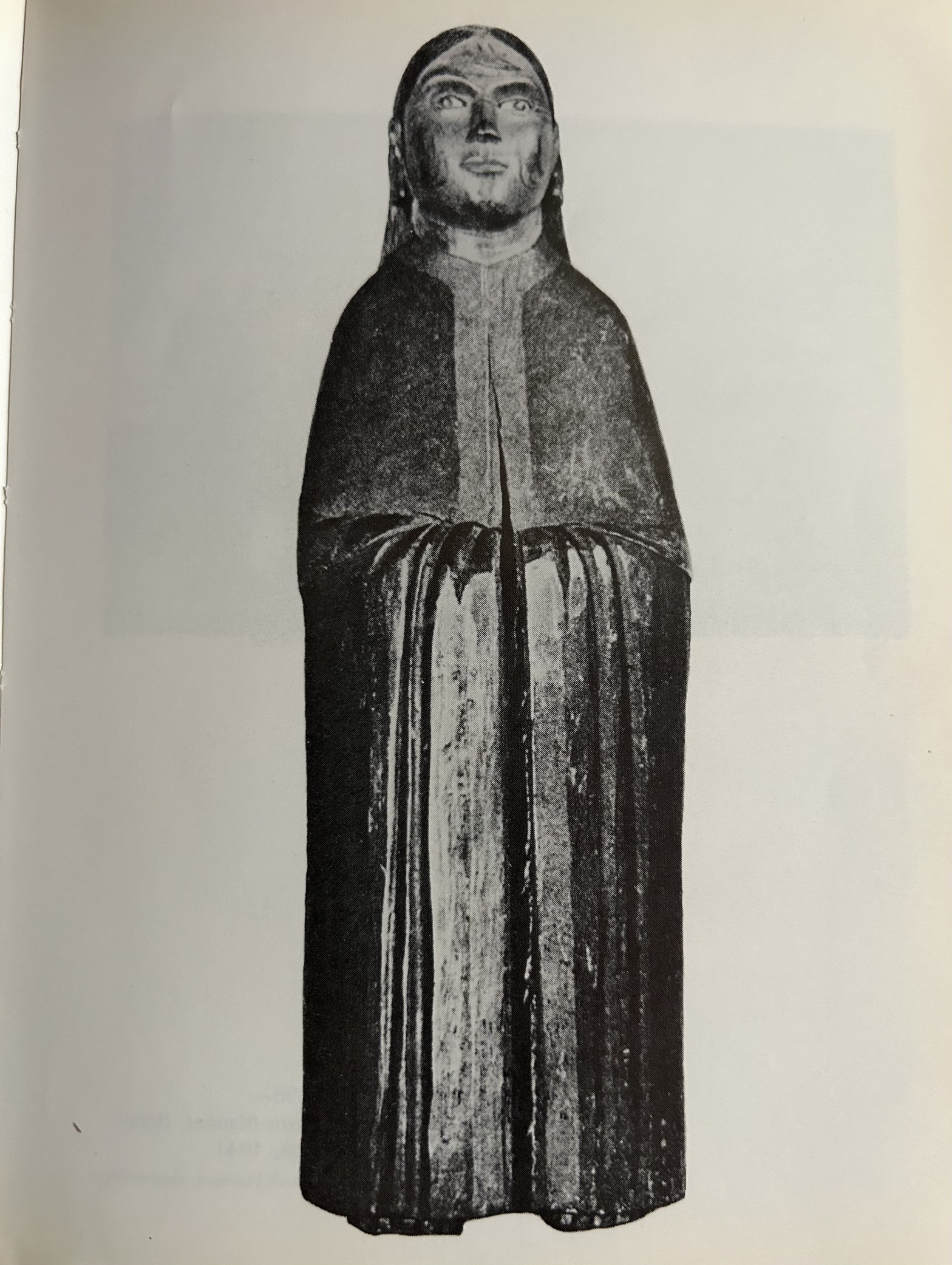

Some years ago, a friend brought this back from India as a gift, and it’s been sitting on my bookshelf ever since:

The hand gesture is based on a famous story in the life of the Buddha:

In one of Buddhism’s iconic images, Gautama Buddha sits in meditation with his left palm upright on his lap, while his right hand touches the earth. Demonic forces have tried to unseat him, because their king, Mara, claims that place under the bodhi tree. As they proclaim their leader’s powers, Mara demands that Gautama produce a witness to confirm his spiritual awakening. The Buddha simply touches the earth with his right hand, and the Earth itself immediately responds: “I am your witness.” Mara and his minions vanish. The morning star appears in the sky. This moment of supreme enlightenment is the central experience from which the whole of the Buddhist tradition unfolds.[i]

He is not just thinking about the earth and what it means, he’s physically connecting himself to the earth. The action symbolizes that the spiritual teachings are not lofty ideas, but literally “grounded” in real life.

This past week, one of Richard Rohr’s daily meditations noted the legacy of Brother Lawrence. Here’s an excerpt:

In the mid-17th century, a man named Nicolas Herman joined the Carmelite monastery in Paris, France. Wounded from fighting in the European Thirty Years’ war, and suffering a sustained leg injury, he took the monastic name “Brother Lawrence of the Resurrection.” He worked in the monastery kitchen and eventually became the head cook. Amid the chaos of food preparation and the clanging of pots and pans, Brother Lawrence began to practice a simple method of prayer that helped him return to an awareness of Divine presence. He called it the practice of the presence of God and described it as “the most sacred, the most robust, the easiest, and the most effective form of prayer.” Brother Lawrence’s method of prayer is so simple that it might seem misleading. It is to cultivate and hand over one’s awareness to God in every moment, in whatever we are doing. Brother Lawrence recommends that newcomers to the prayer use a phrase to recollect their intention toward the Divine presence, such as “‘My God, I am all yours,’ or ‘God of love, I love you with all my heart,’ or ‘Love, create in me a new heart,’ or any other phrases love produces on the spot.”” [ii]

Brother Lawerence summarized what he learned in the little book, The Practice of the Presence of God. I first read it early in my spiritual journey, and have — in my best moments — often remembered it when doing the dishes. Instead of thinking, “This is such a bother – I’m going to finish this job as quickly as possible,” I try to take a Brother Lawerence attitude: “I’m going to slow down and be aware of the tangible experience of this chore: feel each dish in my hand as I pick it up, notice the warmth of the water, appreciate stacking the dishes in the rack one by one, be grateful in these moments of being alive…” I tend to be easily distracted and lost in thought, but doing household chores in the spirit of Brother Lawerence can be a satisfying practice.

Recognizing the way in which daily tasks can “ground us” is a fundamental teaching in the Benedictine monastic tradition, summarized in the phrase “ora et labora.” Every day, a monk spends time in prayer (“ora”) but also manual labor (“labora”); labora can mean cooking and cleaning, working in the garden or, in some pious communities, carefully brewing beer.[iii]

When I was working at La Casa de Maria retreat center, one of our most popular offerings was led by Cynthia Bourgeult, an Episcopal priest and writer. Each person who came to the 5-day retreat could expect regular lectures by Cynthia, times of chanting and worship, and a daily period of physical labor performed in silence. One of our staff responsibilities before the retreat was to come up with a list of manual tasks that retreatants could do, such as raking leaves, weeding gardens or caring for our citrus trees. Sometimes we’d get a call from a person who wanted to register but said they did not see the point of doing any manual labor; Cynthia instructed us to tell the person this was not an option – if they weren’t willing to do it, they should not come at all. She told us that some people who had initially not wanted to do the labor ended the week saying it became one of their most valuable experiences.

I think of the training I received during my hospice time that was based on Zen practices focused on “cultivating presence.” If we are with someone who is in physical or emotional pain, our thoughts and feelings can get tangled up in our concern for the person and we can lose our focus. We were taught to slow down our breathing and become aware of our rear ends in the chair and our feet on the ground, and to imagine the pain passsing through us into the earth. This can free our mind to be remain calm and open as we interact with the person — to be “present” and not distracted or anxious. I have found it to be a worthwhile technique.

Spiritual traditions include specific teachings, participation in community life and the practice of serving others in tangible ways. As our culture becomes more fragmented and people more socially isolated, many studies have demonstrated that being part of spiritual communities leads to increased emotional and physical health. The traditions ground us in what really matters, giving meaning to all we do.

[i] https://www.huffpost.com/entry/buddhism-and-climate-change_b_925651

[ii] https://cac.org/daily-meditations/brother-lawrence-of-the-resurrection/

[iii] Many monastic communities saw beer brewing as a particularly meaningful form of labor, and at one time there were a thousand monastic breweries in Europe. For a current listing, see A List of the World’s Monastic Beers