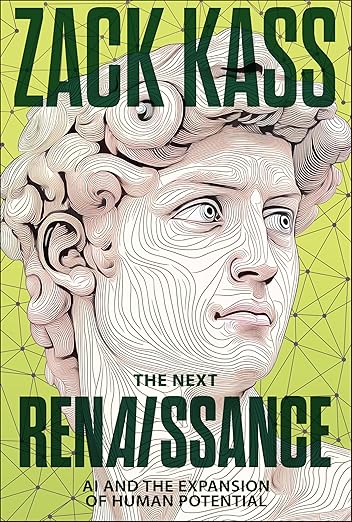

On January 20, I joined a packed crowd at the local Granada Theater to hear a leading promoter of A.I., Zack Kass, give a pitch for his new book, The Next RenAIssance: AI and the Expansion of Human Potential. The local Montecito Journal ran an article describing Zack’s background:

Zack Kass has been at the forefront of the rapidly emerging field of artificial intelligence for nearly 20 years…After several jobs in the machine learning field, Kass joined OpenAI in 2021 as one of the first 100 employees. He served OpenAI as the head of their Go-to-Market – the business unit responsible for introducing a new product to consumers. In that role he built sales, partnerships, and customer success teams to commercialize OpenAI’s research and help launch ChatGPT, turning the company’s cutting-edge R&D into real-world business solutions.

… The book and the event draw on his 16 years in the field, exploring the arrival and continued expansion of Unmetered Intelligence (defined as AI’s ability to deliver limitless cognitive power at near-zero cost), and explaining how that phenomenon stands to reshape the foundations of work, education, science, art, and more.

Zack is an engaging young man – earnest, smart, funny, and passionate about A.I.’s potential. His background is a local-kid-makes-good story, as his father, Dr. Fred Kass, has been a much-loved oncologist in our town for decades. Zack believes many of our fears about AI – from the safety of self-driving cars to the threat of taking away jobs to being misused by scammers and criminals – are challenges will be solved. He feels the upside of AI is almost unlimited in making human life more meaningful and satisfying. He may be right.

But I’m not so sure.

On my way home that night, I remembered two pieces I posted in 2023. I noted what we are facing with A.I. is exciting and new from a technological perspective. But the human psyche has not significantly changed for millennia. We may have grown in our ability to create amazing things and devices, but we have not always demonstrated wisdom in using what we develop. We have impulses that can lead us into places we do not want to be.

In those posts I noted many ancient myths and contemporary movies recognize what can begin as innocent, well-meaning choices can unintentionally result in unleashing forces beyond our control. Stories from our cultural past include the Greek tale of Pandora’s Box and the Biblical stories of the temptation in the Garden of Eden. In our own time, fantasy and sci-fi movies include the original Frankenstein, 2001: A Space Odyssey, the Terminator series, I, Robot, and the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

The next day, I thought of one more cultural work to add to my list: the “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” segment of the 1940 Disney film, Fantasia. I purchased it on AppleTV (only $4.95!) and watched it.

It had been many years since I had seen it. I forgot what a work of art it is. Long before CGI, every image was hand-drawn by Disney artists — 600 alone to create this movie. And they were masters of their craft.

The story begins with Mickey Mouse as an assistant to a powerful Sorcerer who uses his magic to make amazing things happen. He assigns Mickey the job of carrying water back and forth to fill up a cistern and he begins the tedious manual labor. Meanwhile, the Sorcerer takes of his hat, puts it on a table, and leaves. Mickey pauses. He looks at the hat and wonders what it must be like to have such power. He decides to try it on. He puts on the hat and casts a spell on a broom. The broom sprouts two arms and begins hauling water.

As it works, Mickey is pleased with himself and takes a nap. He dreams of having the power to make the stars dance in the sky. But he is woken by the feeling of water surrounding him. It turns out the broom has taken its own initiative and gone beyond the limits of what Mickey had intended. Now the house is flooded. Alarmed, Mickey knows he needs to stop it. He finds an ax and cuts the broom in two. But the broom splinters and becomes a multitude of water carriers working at twice the speed as before. Mickey desperately searches the Sorcerer’s manual for a solution but can’t find one. Just when all seems lost, the Sorcerer returns and sees what has happened. He reverses the spell, the brooms disappear, and the water recedes. He walks up to Mickey and swipes the hat off his head.

Mickey is penitent. Lesson learned.

Poor Mickey. He had seen a compelling opportunity to increase his ability to manipulate the world to make his life easier. But what he creates escapes his control and brings chaos.

Back to Zack’s vision.

More and more people I know are finding A.I. to be useful, delightful and amazing. In many jobs, utilizing A.I. is a requirement. In many areas of our life it is already creating great improvements. I myself have begun to use Claude as an A.I. resource for research and editing. I chose Claude because it does not track, store or sell personal information. Its parent company, Anthropic, is committed to security, safety, and serving the public good. I like it. But I want to be careful.

In recent years, many forces in the private sector and government wanted to establish safeguards to make sure the rapidly expanding power of A.I. is not misused. But last spring the Trump administration appointed David Sacks to oversee government policy. Sacks tossed aside the regulatory initiatives and ever since has been encouraging unhindered development.

That’s exciting to some. But is it wise?

We see what Smartphones did to a generation of children and teenagers. Few people saw that coming. Now, in many schools and communities, restrictions are in place and the results are universally positive. But A.I. dwarfs Smartphones in its capacity to enchant, engage, coopt and overwhelm us.

Since reading his fascinating history of humanity, Sapiens, I have been closely following the opinions of the Israeli historian, anthropologist, and commentator Yuval Noah Harari. In recent years he has been an articulate spokesperson regarding the hidden dangers of A.I.. He spoke last week at the Davos conference in Switzerland. Here’s what a reporter from Forbes Magazine had to say:

I have just had the pleasure of listening to Yuval Noah Harari at Davos 2026. I spend my life thinking and writing about AI, but this still landed with real force. Harari didn’t offer another prediction about automation or productivity, but questioned something deeper: whether we are sleepwalking into a world where humans quietly surrender the one advantage we have always believed made us exceptional.

Harari’s opening was as simple as it was disruptive. “The most important thing to know about AI is that it is not just another tool,” he said. “It is an agent. It can learn and change by itself and make decisions by itself.” Then he delivered the metaphor that cut through the polite Davos nodding. “A knife is a tool. You can use a knife to cut salad or to murder someone, but it is your decision what to do with the knife. AI is a knife that can decide by itself whether to cut salad or to commit murder.”

That framing matters because most of our technology rules assume the old relationship: humans decide, tools execute. Harari’s argument is that AI is beginning to break that relationship, and once it does, the usual models of accountability, regulation and even trust start to wobble. (https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2026/01/21/when-ai-becomes-the-new-immigrant-yuval-noah-hararis-wake-up-call-at-davos-2026/

In Mickey’s case, the Sorcerer reappears and saves the day. But as A.I.’s powers expand far beyond what we can envision and it becomes something more than we could have ever imagined, who or what will be able to stop it from becoming a destructive force?

Zack Kass may be right – the future with AI will be an amazing new world to celebrate. But I’m not so sure. In the recent history of our species, we human beings have often created things with the best intention. But in the process, we conjure up forces that don’t produce the results we intended. There is no Sorcerer who’s going to miraculously show up, take the magic hat off our head, and get everything back to the way it was. This is it.

I’m hope I’m wrong. #3.

The prior posts: https://drjsb.com/2023/04/29/i-hope-im-wrong; https://drjsb.com/2023/05/06/i-hope-im-wrong-part-2-artificial-intelligence-pandoras-box-the-lord-of-the-rings-and-the-garden-of-eden/