During a time when a major conflict was occurring in the Middle East, I invited my friend Rabbi Arthur to speak to my congregation on “The Israeli Perspective.” The week before we’d heard a Palestinian advocate and wanted to hear the other side.

Arthur stood in front of the 35 or so people in the meeting room. Before he answered any of our questions, he introduced us to five Israelis he knew personally. He went to the right side of the room, stood in one spot, and “introduced” us to his first friend. He told us where this person had been born, some formative experiences that had shaped them, when they had come to settle in Israel, and some details of their daily life. He then took several steps sideways and, planting himself in a second spot, introduced us to another friend in the same way. He then moved to the middle of the room and told of a third friend. He did it a fourth time, and then a fifth. He stepped forward and said he was ready for the first question. Someone raised their hand and asked.

“Well,” he said as he walked over to the second spot he’d stood in, “This friend of mine would say…” and proceed to answer the question as that friend would.

“But my other friend…” he said as he walked to the fourth position, “Would say this…” and offered that friend’s perspective. Then he stepped into the fifth spot and said, “And my good friend here sees it a bit differently from the other two. She would tell you this …”

The questions and answers continued for the rest of the hour. He continued answering every question by moving to two or three of the different places in the room where his friends “stood” as he shared each one’s opinion.

When he finished the hour-long presentation, two things were clear: 1) there was no one “Israeli’ position on a particular political issue, but at least five; 2) the position each of his friends took grew out of their personal experiences.

When we go to vote and there are only two candidates, we must pick one. Or if we are voting on a proposition with only “Yes” or “No” options, we must make a choice. That either/or thinking is common in our current culture, and we may be tempted to listen to someone and quickly judge them as “right” or “wrong.” But when we take the time to get to know people and discover why they feel the way they do, we might find out there are more nuances of complexity than we imagine. We are also reminded that peoples’ positions and opinions come out of their specific life experiences.

I knew an education professor who was an articulate advocate for women’s rights. She was often asked to be on a panel where she’d be paired with someone who held a different position. But after several such occasions, she would decline the invitation to speak if the panel was only going to have two perspectives — she insisted at least three be represented.

When I was in Seattle, I took an excellent organizational leadership class. The teacher encouraged us to always be ready to broaden our perspective on possible solutions to a problem. Our habit, he said, was to say, “Let’s get a group together and find a solution.” But he encouraged us to frame it differently: “Let’s get a group together and come up with at least three possible solutions, and then choose one.”

I think of the great spiritual teachers. They offer abiding truths that can apply to everyone. But then there are times when an individual approaches them with a specific question or concern. The teacher pauses and gets a sense of who this individual is and what they’ve faced in their life, and then says something very specific You can see this in the Gospel stories – Jesus will offer one person direct physical healing, another assurance of forgiveness, another a challenge to examine their priorities more carefully, and another a parable that leaves them pondering issues far beyond what they had expected.

Life is full of complexity, and we often don’t have the time, energy, or patience to consider multiple viewpoints. But in situations where we do take the trouble to do so, we may not only get a better understanding of the situation but also gain an appreciation for other people and respect for how they came to see the world they do.

Oliver Wendell Holmes famously said, “For the simplicity that lies this side of complexity, I would not give a fig, but for the simplicity that lies on the other side of complexity, I would give my life.”

Rabbi Arthur was not simply a passive observer without his own opinions. On the contrary, in his life he has never ceased being an advocate and activist for what he believes. So, on the day he spoke to us when people would ask him, “Well — what is your opinion?” he wouldn’t hesitate. He would position himself somewhere along the spectrum and tell us. But we got the point: one can have strong and clear opinions and, at the same time, show genuine respect for those who might see things differently.

Photo: “Five Paths” (Cinco Caminos) by Richard Long, 2004, Es Baluard Museu d’Art Contemporani de Palma, depósito colección Serveis Ferroviaris de Mallorca

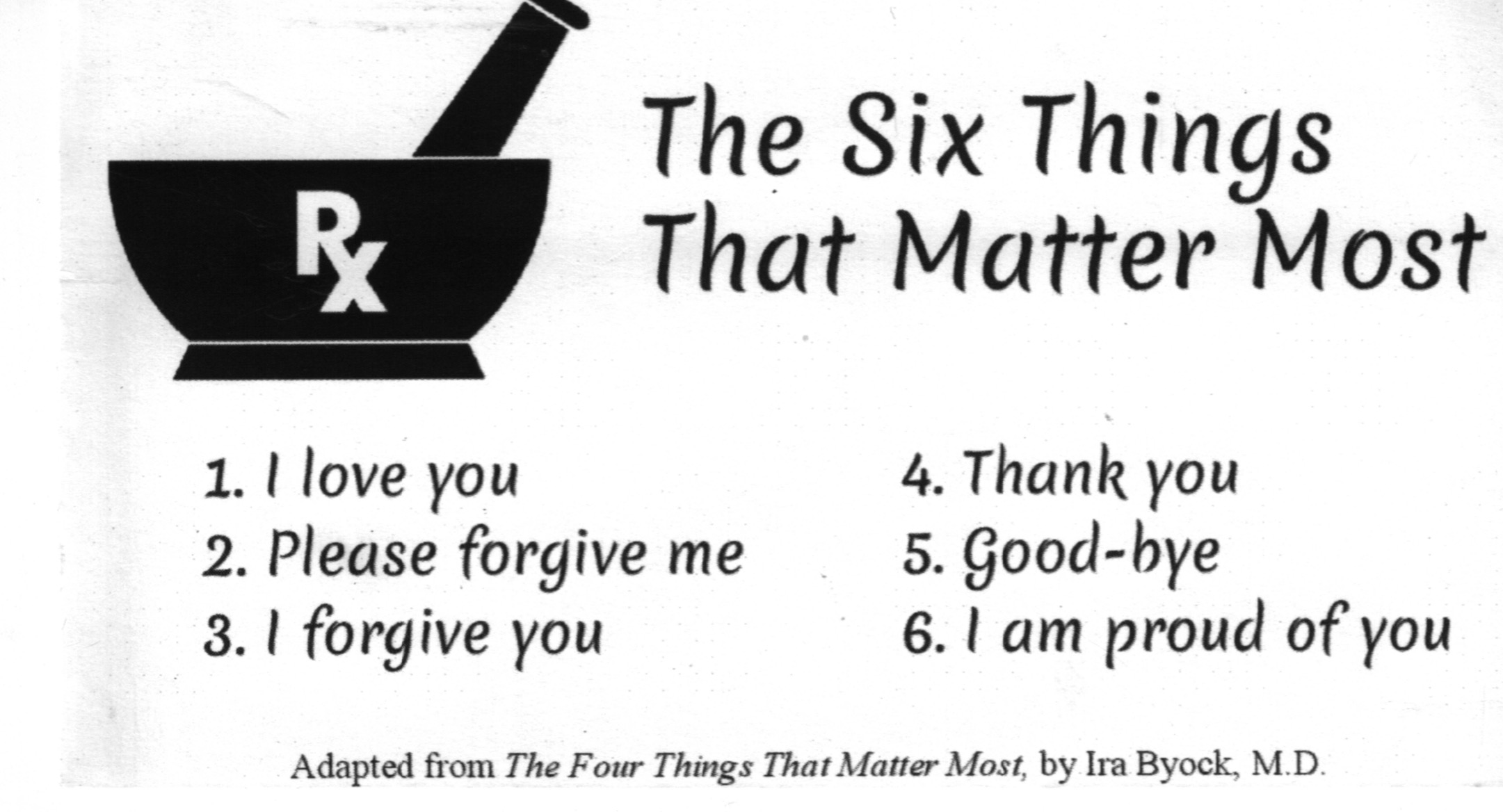

I was grateful to have the card when my father was dying.

He was in his last days at a nursing home. My two sisters and I used the list as a prompt for talking to him. He was no longer responsive, but it felt like the right thing to do. Maybe he heard us or maybe not. Maybe he could sense what we meant through tone or feeling. Or maybe it was just for us.

“Dad, please forgive me for the sleepless nights I gave you as a teenager.”

“There were times when I was growing up when I was afraid of your anger. I knew you were under a lot of pressure and loved us, but it was still scary. I forgive you.”

“Thank you for providing for us, encouraging us and believing in us.”

“For the way you worked so hard to honor mom and provide for us, for the integrity and honesty with which you lived your life, and for your service to our country during the war – we are proud of you.”

Dad wasn’t from a generation when many men would say “I love you.” But we knew he loved us. It was easy for each of us to say, “I love you, Dad.”

The “Goodbye” statement can be tricky. It can be tempting to say it to have some closure, but it may be too early. (I remember one family had asked a harpist to play in the room; the patient woke up and said, “Get that music out of here…I’m not ready for the angels yet!”) But if, say, a family member is leaving town or death is clearly imminent, then “Goodbye” can be fitting.

As I did presentations on hospice in the community, I would pass these cards out. People would later tell me how helpful they were.

But I also knew what everyone who works in hospice knows…the work is not just about the dying, but also about the living. Whether dad was fully aware of what we were saying, it gave us closure.

The list can also be helpful after a death when we didn’t have an opportunity to speak the words in person. We can write a letter to the person using the list as possible prompts. We can then save the letter just for ourselves. Or we can take it to a place we associate with the person, including a gravesite, and read it. When it’s served its purpose, we can keep it or create a simple ritual and burn it.

“Six Things” can also be valuable when death is not on the horizon. Roughly half of Americans die with some form of hospice care, which means there may be time for meaningful bedside moments. It also means the other half of us will die without such an opportunity – heart attacks, strokes, accidents, etc. If these are the six things that matter most, why wait for a moment that we may never have? Why not use them when we are alive and well?

As time went on, I’ve found the “Six Things” a good way to take inventory from time to time in my own life on occasions like anniversaries and birthdays. Is there someone I want to say these words to now since there’s no guarantee I’ll have a chance in the future? Or maybe take one each day, and say it to someone during the day if the time feels right? It doesn’t have to be a dramatic act, just a sincere one. What do we have to lose? Once we do it, we often experience a sense of freedom.

I was grateful to have the card when my father was dying.

He was in his last days at a nursing home. My two sisters and I used the list as a prompt for talking to him. He was no longer responsive, but it felt like the right thing to do. Maybe he heard us or maybe not. Maybe he could sense what we meant through tone or feeling. Or maybe it was just for us.

“Dad, please forgive me for the sleepless nights I gave you as a teenager.”

“There were times when I was growing up when I was afraid of your anger. I knew you were under a lot of pressure and loved us, but it was still scary. I forgive you.”

“Thank you for providing for us, encouraging us and believing in us.”

“For the way you worked so hard to honor mom and provide for us, for the integrity and honesty with which you lived your life, and for your service to our country during the war – we are proud of you.”

Dad wasn’t from a generation when many men would say “I love you.” But we knew he loved us. It was easy for each of us to say, “I love you, Dad.”

The “Goodbye” statement can be tricky. It can be tempting to say it to have some closure, but it may be too early. (I remember one family had asked a harpist to play in the room; the patient woke up and said, “Get that music out of here…I’m not ready for the angels yet!”) But if, say, a family member is leaving town or death is clearly imminent, then “Goodbye” can be fitting.

As I did presentations on hospice in the community, I would pass these cards out. People would later tell me how helpful they were.

But I also knew what everyone who works in hospice knows…the work is not just about the dying, but also about the living. Whether dad was fully aware of what we were saying, it gave us closure.

The list can also be helpful after a death when we didn’t have an opportunity to speak the words in person. We can write a letter to the person using the list as possible prompts. We can then save the letter just for ourselves. Or we can take it to a place we associate with the person, including a gravesite, and read it. When it’s served its purpose, we can keep it or create a simple ritual and burn it.

“Six Things” can also be valuable when death is not on the horizon. Roughly half of Americans die with some form of hospice care, which means there may be time for meaningful bedside moments. It also means the other half of us will die without such an opportunity – heart attacks, strokes, accidents, etc. If these are the six things that matter most, why wait for a moment that we may never have? Why not use them when we are alive and well?

As time went on, I’ve found the “Six Things” a good way to take inventory from time to time in my own life on occasions like anniversaries and birthdays. Is there someone I want to say these words to now since there’s no guarantee I’ll have a chance in the future? Or maybe take one each day, and say it to someone during the day if the time feels right? It doesn’t have to be a dramatic act, just a sincere one. What do we have to lose? Once we do it, we often experience a sense of freedom.