This week our grandson’s Little League practice was at the neighborhood school. Besides 5-year-old boys playing baseball, girls’ basketball and boys’ soccer teams were practicing. Kids, parents, and grandparents were meandering around, chatting, and watching. Toddlers were on the playground equipment. It felt normal.

And then it came to me: not too long ago, this scene would not have been possible.

I remember I’d posted a piece about the playground and checked when I got home. I found this from March 14, 2021:

This past Monday, I was driving past our neighborhood school at lunchtime and saw something I had not seen in a year: children playing. Outdoors. On the school property. Lots of them. On their own. They were chasing balls and chasing each other. Some were sitting in pairs on the grass, some were walking around on their own, and some were involved with games on the blacktop. In the 27 years we have lived in this neighborhood, I’ve gone by the school almost every day, but it’s been a year since I’ve seen children playing at recess…

COVID had shut down schools, playgrounds, and parks all over the world for a year. When I saw that scene last year and realized we were getting back to “normal” I vowed to never take such “normal” scenes for granted again.

COVID is still out there, but almost no one is dying from it. A few places still recommend masks. Much of our life is “back to normal.” I have often forgotten what we went through. But perhaps we should not forget too quickly how different our lives were.

Just now, I opened my wallet and took out my battered vaccination card. In early February, 2021, a friend and I were able to get online appointments for some of the first vaccines being offered. On our scheduled Saturday, we drove two hours to Dodger Stadium. We then spent four hours inching along in a long line of cars into the vast parking lot where the shots were being administered. Finally, we arrived at the place where a masked and gloved nurse approached us. I rolled down my window and offered her my left arm. She gave me the injection and said, “Sir, you have been vaccinated.” I’ll never forget those words or what it felt like. I guess I don’t need to carry the card with me anymore, but I’m going to keep it as a reminder.

I remember reading David Brooks’ comment in the New York Times as COVID was ending in New York. He pledged he would never again let himself be impatient at a crowded bar while waiting to order a drink. He is scheduled to speak in Santa Barbara this spring, and if I get a chance, I want to ask him if he’s been able to honor that commitment.

I remember a column from the conservative commentator Peggy Noonan in the Wall Street Journal during the most desperate days of COVID. At that point, we were all dependent on the “front-line workers” in fields, stores, delivery trucks, and hospitals who were keeping us alive at serious risk to themselves. She said when the pandemic was over, any undocumented worker who had been on those front lines should be given a guaranteed path to citizenship. I have not seen her or anyone mention that issue since. If I ever bump into her – maybe at a crowded bar in New York? — I will ask her if she still favors that position.

In many ways, life is back to normal. But I don’t want to forget what we went through. I don’t want to forget how grateful we can be for where we are now. I don’t want to forget those who risked their lives to keep us safe, nor ever lose our gratitude for those who developed the vaccine.

It’s a beautiful thing to see kids playing baseball outdoors.

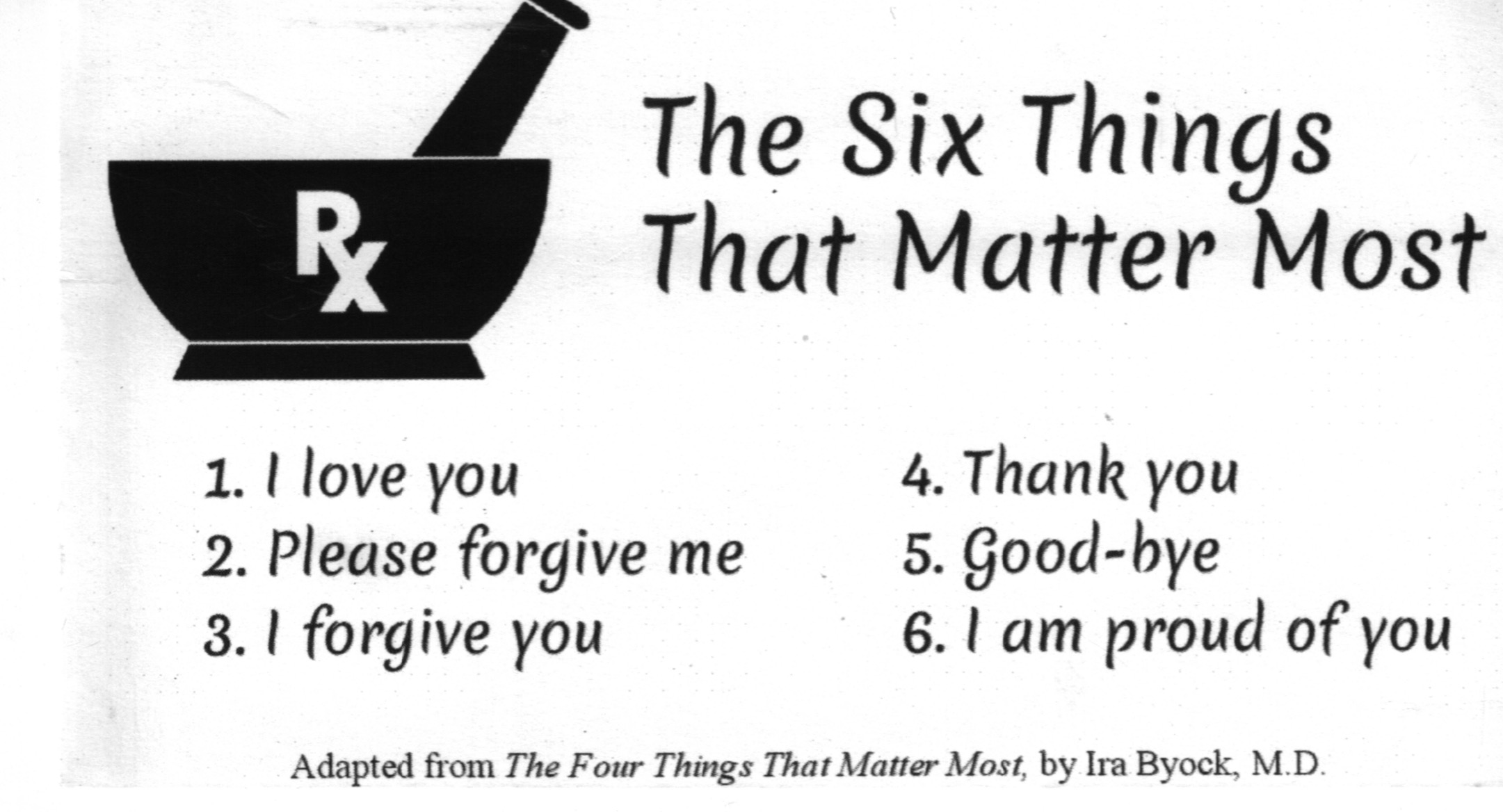

I was grateful to have the card when my father was dying.

He was in his last days at a nursing home. My two sisters and I used the list as a prompt for talking to him. He was no longer responsive, but it felt like the right thing to do. Maybe he heard us or maybe not. Maybe he could sense what we meant through tone or feeling. Or maybe it was just for us.

“Dad, please forgive me for the sleepless nights I gave you as a teenager.”

“There were times when I was growing up when I was afraid of your anger. I knew you were under a lot of pressure and loved us, but it was still scary. I forgive you.”

“Thank you for providing for us, encouraging us and believing in us.”

“For the way you worked so hard to honor mom and provide for us, for the integrity and honesty with which you lived your life, and for your service to our country during the war – we are proud of you.”

Dad wasn’t from a generation when many men would say “I love you.” But we knew he loved us. It was easy for each of us to say, “I love you, Dad.”

The “Goodbye” statement can be tricky. It can be tempting to say it to have some closure, but it may be too early. (I remember one family had asked a harpist to play in the room; the patient woke up and said, “Get that music out of here…I’m not ready for the angels yet!”) But if, say, a family member is leaving town or death is clearly imminent, then “Goodbye” can be fitting.

As I did presentations on hospice in the community, I would pass these cards out. People would later tell me how helpful they were.

But I also knew what everyone who works in hospice knows…the work is not just about the dying, but also about the living. Whether dad was fully aware of what we were saying, it gave us closure.

The list can also be helpful after a death when we didn’t have an opportunity to speak the words in person. We can write a letter to the person using the list as possible prompts. We can then save the letter just for ourselves. Or we can take it to a place we associate with the person, including a gravesite, and read it. When it’s served its purpose, we can keep it or create a simple ritual and burn it.

“Six Things” can also be valuable when death is not on the horizon. Roughly half of Americans die with some form of hospice care, which means there may be time for meaningful bedside moments. It also means the other half of us will die without such an opportunity – heart attacks, strokes, accidents, etc. If these are the six things that matter most, why wait for a moment that we may never have? Why not use them when we are alive and well?

As time went on, I’ve found the “Six Things” a good way to take inventory from time to time in my own life on occasions like anniversaries and birthdays. Is there someone I want to say these words to now since there’s no guarantee I’ll have a chance in the future? Or maybe take one each day, and say it to someone during the day if the time feels right? It doesn’t have to be a dramatic act, just a sincere one. What do we have to lose? Once we do it, we often experience a sense of freedom.

I was grateful to have the card when my father was dying.

He was in his last days at a nursing home. My two sisters and I used the list as a prompt for talking to him. He was no longer responsive, but it felt like the right thing to do. Maybe he heard us or maybe not. Maybe he could sense what we meant through tone or feeling. Or maybe it was just for us.

“Dad, please forgive me for the sleepless nights I gave you as a teenager.”

“There were times when I was growing up when I was afraid of your anger. I knew you were under a lot of pressure and loved us, but it was still scary. I forgive you.”

“Thank you for providing for us, encouraging us and believing in us.”

“For the way you worked so hard to honor mom and provide for us, for the integrity and honesty with which you lived your life, and for your service to our country during the war – we are proud of you.”

Dad wasn’t from a generation when many men would say “I love you.” But we knew he loved us. It was easy for each of us to say, “I love you, Dad.”

The “Goodbye” statement can be tricky. It can be tempting to say it to have some closure, but it may be too early. (I remember one family had asked a harpist to play in the room; the patient woke up and said, “Get that music out of here…I’m not ready for the angels yet!”) But if, say, a family member is leaving town or death is clearly imminent, then “Goodbye” can be fitting.

As I did presentations on hospice in the community, I would pass these cards out. People would later tell me how helpful they were.

But I also knew what everyone who works in hospice knows…the work is not just about the dying, but also about the living. Whether dad was fully aware of what we were saying, it gave us closure.

The list can also be helpful after a death when we didn’t have an opportunity to speak the words in person. We can write a letter to the person using the list as possible prompts. We can then save the letter just for ourselves. Or we can take it to a place we associate with the person, including a gravesite, and read it. When it’s served its purpose, we can keep it or create a simple ritual and burn it.

“Six Things” can also be valuable when death is not on the horizon. Roughly half of Americans die with some form of hospice care, which means there may be time for meaningful bedside moments. It also means the other half of us will die without such an opportunity – heart attacks, strokes, accidents, etc. If these are the six things that matter most, why wait for a moment that we may never have? Why not use them when we are alive and well?

As time went on, I’ve found the “Six Things” a good way to take inventory from time to time in my own life on occasions like anniversaries and birthdays. Is there someone I want to say these words to now since there’s no guarantee I’ll have a chance in the future? Or maybe take one each day, and say it to someone during the day if the time feels right? It doesn’t have to be a dramatic act, just a sincere one. What do we have to lose? Once we do it, we often experience a sense of freedom.