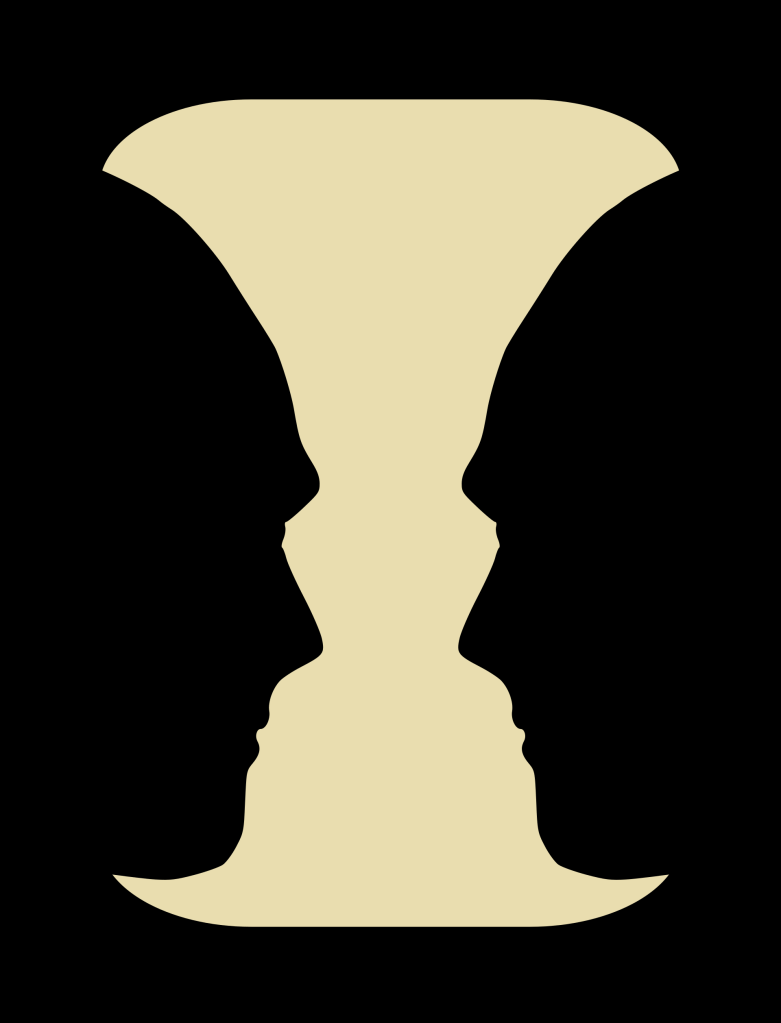

In the eighties, a seminary friend underwent a kind of conversion. He’d been raised with an older form of theology which held that this life is full of sin and suffering, and our best response is to focus on the hope of heaven. But he became convinced that this perspective was misguided. It had led our culture into an attitude of disregarding the integrity and sanctity of creation, which in turn contributed to the degradation of the environment; it also kept us from appreciating the blessings present in everyday life. He began to see divine life embedded in the natural world and became an early supporter of the “eco-spirituality” movement. “Faith isn’t just about the pie in the sky,” he’d say, “the sky is in the pie.” In other words, the divine presence surrounds us, and a primary spiritual calling in our time is to protect and nurture the earth and appreciate all that it offers.

A turning point for me was reading Original Blessing, by the feisty priest and scholar, Matthew Fox. Fox pointed out that Western theology had mistakenly become fixated on the doctrine of “original sin” in the fourth century and has never let it go. But the Hebrew Scriptures – and Jesus’ teaching — are pervaded with the theme of life being a miraculous gift, not a curse.

I appreciate the times in human history when peoples’ lives were full of suffering and focusing on future life in heaven – “pie in the sky” – made sense. There are many great spirituals with that theme, and no doubt they were powerful medicine. I honor and appreciate that experience. But if that is the sole focus of our spiritual life, we are missing so much.

I confess I come to this theme with a formidable bias – since the time I was a kid, I’ve loved pies. It started with Mom’s apple pie. Then it expanded to lemon meringue pies at Denny’s. It grew further with a masterpiece made with home-grown pie cherries from the baker’s tree in her backyard. These all tasted “heavenly” to me; literal affirmations that “the sky” can be experienced “in the pie.”

I remember the first time I stayed at a monastery — St. Andrew’s Priory near Pearblossom. I was expecting to be served some kind of thin gruel. But when I came into the dining room, a great, multicourse feast was laid out. It turned out they were welcoming a new novice to their community, so it was my good fortune to be there as they celebrated with this banquet. I later learned that the monk who cooked that night had been a chef with the Hyatt Regency before taking his vows.

Several years later I was spending a day at Mt. Calvary Monastery here in Santa Barbara. Before lunch was served, the host said, “We don’t know if God has taste buds, so we consider it a spiritual duty to enjoy what we eat.”

I’m hoping I can have it both ways. If there is “pie in the sky” after this life is over, I’m all for it. But I’m not missing any opportunities on this side of the great mystery. I’m hoping to have my pie and eat it too.

What’s for dessert?