Our family just celebrated a wedding. The bride and groom wanted a simple gathering, so we did not hire a professional photographer. Instead, many of us took photos and videos with our phones. We are in the process of sharing the best ones with each other and posting several on social media. Undoubtedly, some will become treasured reminders of the love and joy we felt as we celebrated.

In my lifetime, we’ve gone from Brownies to Polaroids to Instamatics to cell phones to Smartphones. The taking, editing, and storing of photographs and movies have never been easier. I recently checked how many I have stored on my computer: 2,940 photos and 422 videos. I have reviewed them more than once, wanting to delete as many as possible. But it’s not easy. For one thing, digital files do not take up physical space – quite a contrast to the boxes and boxes of old albums, prints, and negatives many of our parents left behind. And the photos are often of a family member or friend; as I gaze at them, I cherish the moment the picture was taken and what it means — a moment in my life I’m not yet ready to release.

All this has led me to reflect on the evolution of photography in our personal lives.

As you may know, the first practical process for creating “photographs” was developed in the late 1820s by the French painter and physicist, Louis Daguerre:

The daguerreotype was best suited for still objects, but people nonetheless lined up to have their portraits taken. This was not for the faint of heart: subjects had to sit in blazing sunlight for up to half an hour, trying not to blink, with their heads clamped in place to keep them still. It’s not surprising that most of the early daguerreotype portraits feature grim, slightly desperate faces.”[i]

(The last comment is comforting. When someone is taking my photograph and asks me to smile, I can summon a natural smile quickly, but alas, after five or ten seconds, it melts into just such a grimace.)

Here are two of the earliest existing daguerreotypes:[ii]

Even with such serious “I’ve-been-holding-this-pose-for-thirty-minutes” expressions, don’t you still feel like you can sense something about each one’s character?

An original daguerreotype is a small picture, generally smaller than the palm of one’s hand, and exists on a surface of highly polished silver. The image, though infinitely detailed and subtle, is elusive. The picture should be looked at with its case not fully opened, preferably in private and by lamplight, as one would approach a secret.[iii]

Perhaps looking at an image “as one would approach a secret” increases the experience of awe. Maybe we should always hold them in such reverence to remind us that, in many ways, we will always be an elusive mystery to ourselves and each other.

An early professional daguerreotype photographer remarked on people’s reaction to their portraits: “People were afraid at first to look for any length of time at the pictures he produced. They were embarrassed by the clarity of these figures and believed that the little, tiny faces of the people in the pictures could see out at them, so amazing did the unaccustomed detail and the unaccustomed truth to nature of the first daguerreotypes appear to everyone.”[iv]

My mother has been gone for almost thirty years, but when one of my sisters recently discovered an old Super 8 home movie of her dancing on a beach, I felt like I was reexperiencing her spirit. And when I see certain photos or videos of our children when they were young, I am often surprised as I’m reminded that their unique personalities have not changed as they’ve become adults. It feels like the “people in the pictures” can “see out” at me – it’s uncanny, and it’s a wonder.

For every photo or video we keep, there are many we delete. We want to remember ourselves and our loved ones in our “best” moments, not when we may look awkward, unhappy, or off-guard. “Smile!” is what we say when taking a picture. But we are all a collection of moods and moments — noble and charming ones, and ones we’d rather forget. If we truly love someone, it’s not just for the best moments, but the not-so-great ones as well. That’s what love in the truest spiritual sense means.

[i] https://www.garrisonkeillor.com/radio/twa-the-writers-almanac-for-august-19-2022/

[ii] https://www.vintag.es/2016/01/the-very-first-photographs-of-world-21.html

[iii] Looking at Photographs: 100 Pictures from the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, John Szarkowski, pg. 14

[iv] https://www.garrisonkeillor.com/radio/twa-the-writers-almanac-for-august-19-2022/

Top Image: “Earliest Known Photos of People Smiling,” https://petapixel.com/2015/04/15/the-earliest-known-photos-of-people-smiling/

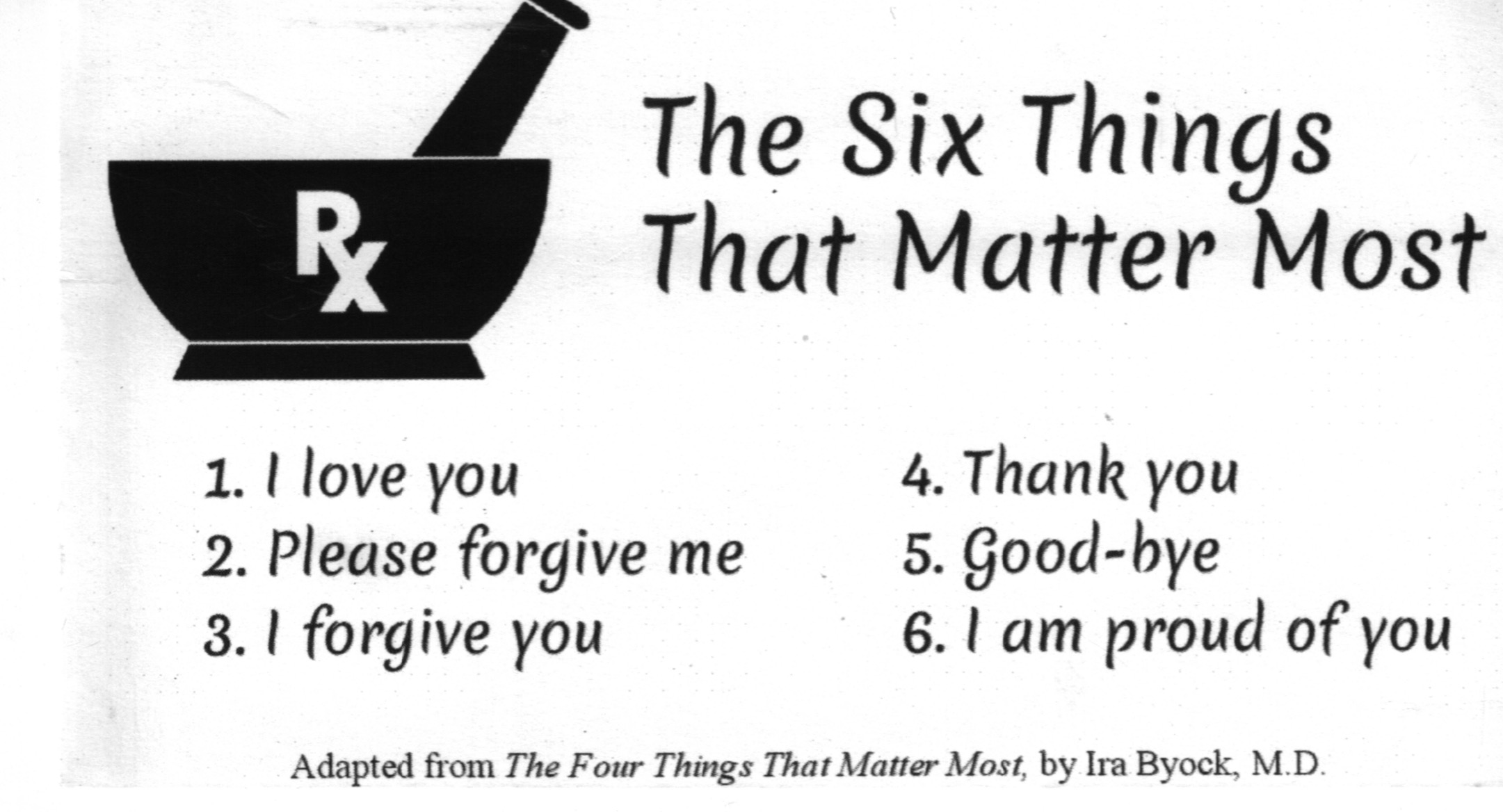

I was grateful to have the card when my father was dying.

He was in his last days at a nursing home. My two sisters and I used the list as a prompt for talking to him. He was no longer responsive, but it felt like the right thing to do. Maybe he heard us or maybe not. Maybe he could sense what we meant through tone or feeling. Or maybe it was just for us.

“Dad, please forgive me for the sleepless nights I gave you as a teenager.”

“There were times when I was growing up when I was afraid of your anger. I knew you were under a lot of pressure and loved us, but it was still scary. I forgive you.”

“Thank you for providing for us, encouraging us and believing in us.”

“For the way you worked so hard to honor mom and provide for us, for the integrity and honesty with which you lived your life, and for your service to our country during the war – we are proud of you.”

Dad wasn’t from a generation when many men would say “I love you.” But we knew he loved us. It was easy for each of us to say, “I love you, Dad.”

The “Goodbye” statement can be tricky. It can be tempting to say it to have some closure, but it may be too early. (I remember one family had asked a harpist to play in the room; the patient woke up and said, “Get that music out of here…I’m not ready for the angels yet!”) But if, say, a family member is leaving town or death is clearly imminent, then “Goodbye” can be fitting.

As I did presentations on hospice in the community, I would pass these cards out. People would later tell me how helpful they were.

But I also knew what everyone who works in hospice knows…the work is not just about the dying, but also about the living. Whether dad was fully aware of what we were saying, it gave us closure.

The list can also be helpful after a death when we didn’t have an opportunity to speak the words in person. We can write a letter to the person using the list as possible prompts. We can then save the letter just for ourselves. Or we can take it to a place we associate with the person, including a gravesite, and read it. When it’s served its purpose, we can keep it or create a simple ritual and burn it.

“Six Things” can also be valuable when death is not on the horizon. Roughly half of Americans die with some form of hospice care, which means there may be time for meaningful bedside moments. It also means the other half of us will die without such an opportunity – heart attacks, strokes, accidents, etc. If these are the six things that matter most, why wait for a moment that we may never have? Why not use them when we are alive and well?

As time went on, I’ve found the “Six Things” a good way to take inventory from time to time in my own life on occasions like anniversaries and birthdays. Is there someone I want to say these words to now since there’s no guarantee I’ll have a chance in the future? Or maybe take one each day, and say it to someone during the day if the time feels right? It doesn’t have to be a dramatic act, just a sincere one. What do we have to lose? Once we do it, we often experience a sense of freedom.

I was grateful to have the card when my father was dying.

He was in his last days at a nursing home. My two sisters and I used the list as a prompt for talking to him. He was no longer responsive, but it felt like the right thing to do. Maybe he heard us or maybe not. Maybe he could sense what we meant through tone or feeling. Or maybe it was just for us.

“Dad, please forgive me for the sleepless nights I gave you as a teenager.”

“There were times when I was growing up when I was afraid of your anger. I knew you were under a lot of pressure and loved us, but it was still scary. I forgive you.”

“Thank you for providing for us, encouraging us and believing in us.”

“For the way you worked so hard to honor mom and provide for us, for the integrity and honesty with which you lived your life, and for your service to our country during the war – we are proud of you.”

Dad wasn’t from a generation when many men would say “I love you.” But we knew he loved us. It was easy for each of us to say, “I love you, Dad.”

The “Goodbye” statement can be tricky. It can be tempting to say it to have some closure, but it may be too early. (I remember one family had asked a harpist to play in the room; the patient woke up and said, “Get that music out of here…I’m not ready for the angels yet!”) But if, say, a family member is leaving town or death is clearly imminent, then “Goodbye” can be fitting.

As I did presentations on hospice in the community, I would pass these cards out. People would later tell me how helpful they were.

But I also knew what everyone who works in hospice knows…the work is not just about the dying, but also about the living. Whether dad was fully aware of what we were saying, it gave us closure.

The list can also be helpful after a death when we didn’t have an opportunity to speak the words in person. We can write a letter to the person using the list as possible prompts. We can then save the letter just for ourselves. Or we can take it to a place we associate with the person, including a gravesite, and read it. When it’s served its purpose, we can keep it or create a simple ritual and burn it.

“Six Things” can also be valuable when death is not on the horizon. Roughly half of Americans die with some form of hospice care, which means there may be time for meaningful bedside moments. It also means the other half of us will die without such an opportunity – heart attacks, strokes, accidents, etc. If these are the six things that matter most, why wait for a moment that we may never have? Why not use them when we are alive and well?

As time went on, I’ve found the “Six Things” a good way to take inventory from time to time in my own life on occasions like anniversaries and birthdays. Is there someone I want to say these words to now since there’s no guarantee I’ll have a chance in the future? Or maybe take one each day, and say it to someone during the day if the time feels right? It doesn’t have to be a dramatic act, just a sincere one. What do we have to lose? Once we do it, we often experience a sense of freedom.