In my years in ministry and hospice, one of the common tasks was caring for people. It sounds easy, but it can be challenging. A key theme is remembering the difference between curing and caring.

Imagine you are going to visit someone who’s dealing with a difficult event. Maybe they’ve lost a loved one or are facing a serious challenge with their health or family.

As you walk up to the door, what is your intention?

A common response would be, “I want to help this person feel better. I’ll do whatever I can to cheer them up. Maybe I can tell them something I went through that will help.”

If this is your intention, how is your body feeling? For most of us, it could be tense. It’s like we are stepping on stage for a performance, and the adrenalin is starting to flow.

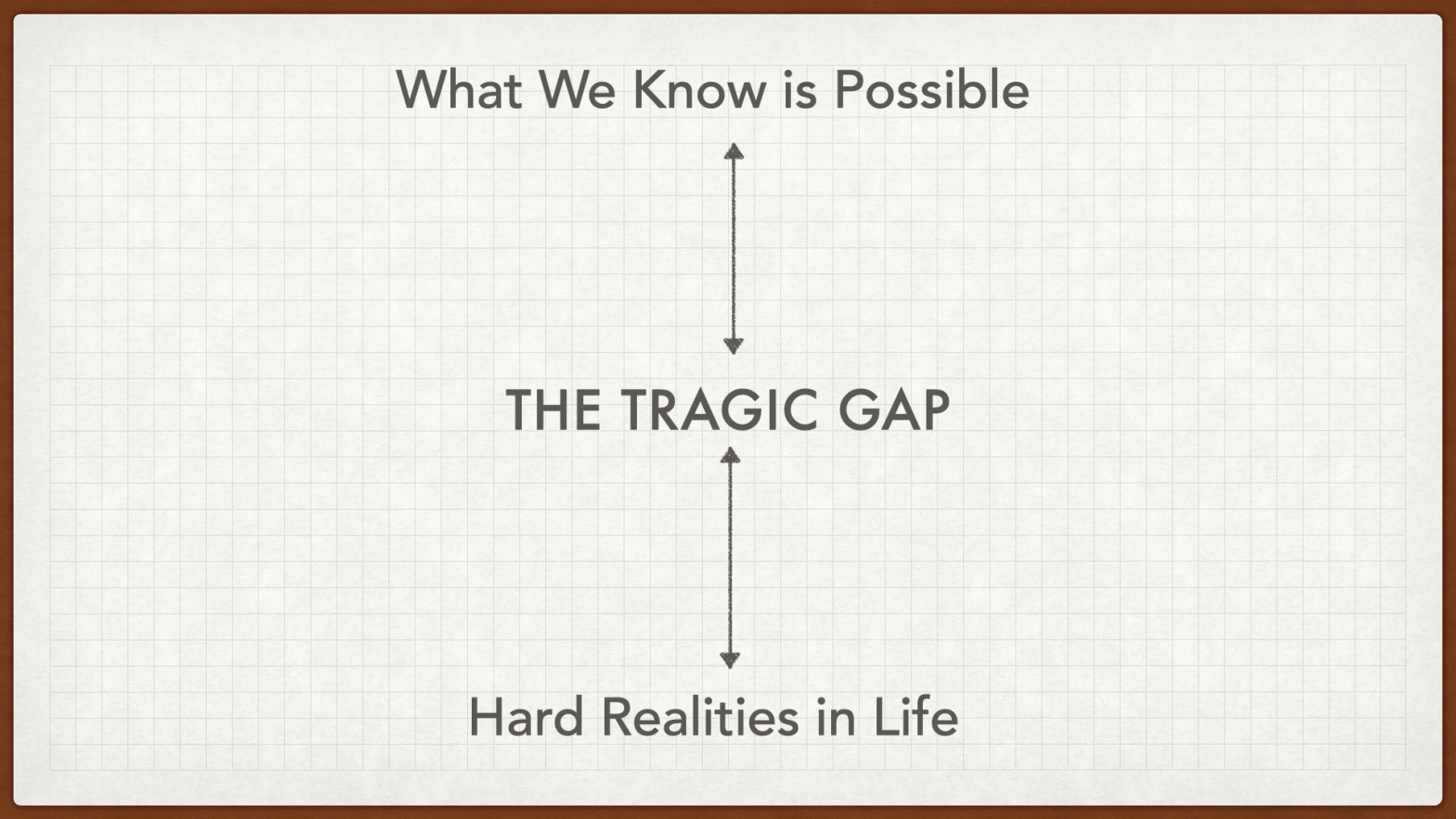

One way to describe this intention is simple: we want to cure this person. Obviously, we can’t bring their loved one back or change what is happening. But maybe if we work hard enough, we can “cure” them of feeling anxious, lost, or depressed with some good advice and encouragement.

We go in and visit. We talk about different things, and whenever we can, insert an upbeat comment or personal story. If there is a pause in the conversation, we think of something to talk about so it’s not awkward.

The visit concludes. We exchange good wishes, step out and close the door.

What might we be thinking and feeling?

We may be glad to know we made the visit to show our concern, but we’re probably relieved the visit is over. It’s stressful to have to fix other people. We may also sense that, despite whatever well-intended words we said, our friend is not really “better.”

How might the person we visited be feeling?

They may have picked up on the dynamic created by our intention to “cure them.” They didn’t want us to feel bad, so they played along, forcing a smile when they could and in the end thanking us for coming. But they may also be relieved when the visit is over. They may feel guilty that their situation is creating stress and concern for others.

All this can flow when we try to cure people.

Let’s start with a different intention. Instead of trying to cure the person, we are simply going to care for them.

As we come up to their door, we pause to clarify that intention. We say to ourselves, “I’m not here to change how they are feeling. I am going to listen carefully to what their situation is really like for them. If they describe their pain or confusion, I’m not going to redirect them. I’m going to simply be with them, listening to them with a sense of genuine, restrained reverence.”

So, in we go. We do our best to truly listen to what they are saying. Our own mind may want to interject an opinion aimed at changing how they feel, but we let those thoughts dissipate. Whatever unfolds, we simply try to come alongside and truly appreciate what they are experiencing in all its complexity.

In a simple form, that’s caring instead of curing.

A leading grief counselor, Alan Wolfelt, has another word for caring: companioning. He believes grief is ultimately a journey of the soul that needs to be honored, not a psychological problem that needs to be fixed. Here’s a few of what he calls the essential tenets of companioning:

Tenet One: Companioning is about being present to another person’s pain; it is not about taking away the pain.

Tenet Two: Companioning is about going to the wilderness of the soul with another human being; it is not about thinking you are responsible for finding the way out.

Tenet Seven: Companioning is about discovering the gifts of sacred silence; it does not mean filling up every moment with words.

Tenet Nine: Companioning is about respecting disorder and confusion; it is not about imposing order and logic. (For a full list, go to https://www.centerforloss.com/2019/12/eleven-tenets-of-companioning)

As you can see, it’s very different from curing. The focus is fully on the other person, not my need to prove myself. To be truly “companioning” is not a performance that summons adrenalin, but a spiritual practice in which we seek to be calm, alert, and unafraid.

When I’m practicing being a “companion,” I’m not being passive. My mind, heart and body are active as they attune to the person’s experience. But I’m not going to grab the steering wheel and direct the conversation the first chance I get.

Some years ago, the agency I worked for received a request from a local retirement home to have one of our people visit a new resident. The woman’s children had initiated the move so they could be closer to her. But in the process, she had to give up a lifetime of relationships in the community back east where she’d lived all her life. Since moving in, she rarely came out of her apartment and the staff was concerned.

On the first visit, they simply became acquainted. But by the second visit, she sensed she could be open about the pain she was experiencing. She began sobbing intensely, which went on for 40 minutes. The counselor simply sat there with her. When he arrived for the next visit, she said, “It’s a beautiful day. Let’s take a walk outside,” and she showed him some of the beautiful flowers near her apartment. He visited her once more and they parted ways.

He didn’t cure her. But he honored and cared for her like a trusted companion, and a new chapter in her journey could begin.