Years ago, a wise therapist said: “Steve, remember– love is a combination of care and confrontation.” That came as a shock. I had assumed “love” only meant “care.” But over the years I’ve reflected on this insight many times.

This week I will explore how this perspective on love is reflected in our spiritual journeys. I am going to let Rembrandt’s understanding of Jesus do most of the work by considering one of his masterpieces, “The Hundred Guilder Print” from 1650.

If you look at the full picture, what do you see? At first glance, it may look like just a pleasant portrayal of Jesus amid a crowd. It’s easy to identify him – he’s at the center, with rays of light shining from his face. But a closer look reveals it’s a not just a visual dose of religious saccharine, but a multifaceted masterpiece.

Rembrandt took Chapter 19 from the Gospel of Matthew and imagined how Jesus was interacting with each character in the story.

Let’s start with the right half of the picture, illustrating verses 1-2: “…large crowds followed him, and he cured them there.” Rembrandt imagines the various sicknesses and disabilities of the time and uses a variety of facial expressions and postures to show each person as they hope for healing. The compassion he showed such people is what I think of as “caring.”

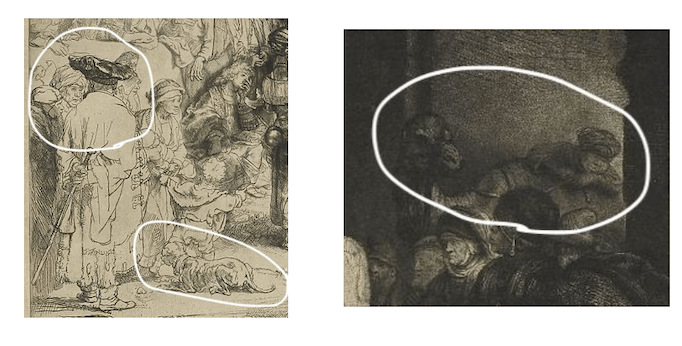

But the mood changes as we shift to the left side. In verses 3-12, Pharisees pose a hard question about marriage and divorce. Jesus gives them a provocative response and they are discussing it. Loving these people meant challenging their beliefs.

In verses 13-15, a woman brings her child for a blessing. The disciples “speak sternly to her” implying a woman with a child shouldn’t bother Jesus. But he contradicts his disciples, putting his right hand in front of Peter (personifying the disciples) to silence him. Peter gets “the back of his hand,” but the palm of that same hand opens to welcome the woman. Behind her is a woman who has a baby in her arms; a second child is tugging on her sleeve, encouraging her to also accept the invitation. In this one hand gesture, Jesus is rebutting Peter and welcoming the women and children – confronting and caring at the same time. (As one feminist scholar has pointed out, this is a common dynamic in the Gospels – in scenes where both women and men are present, Jesus often speaks and acts in a way that humbles men and affirms women.)

We now focus on a character described as a “rich young man” (verses 16-22). He asks what he needs to do to deepen his spiritual life. Jesus first cites the Ten Commandments, assuming that is sufficient. The young man says he has done that but still feels something is lacking. I imagine Jesus pauses and looks more deeply into the man’s eyes before telling him he needs to sell all he has, give the proceeds to the poor, and follow him. “He went away grieving, for he had many possessions.” Rembrandt pictures the young man in deep introspection before leaving. His conversation with this young man – confrontation? Or care? Or both?

In many traditional religious paintings, every character is depicted as being in adoring rapture, surrounded by heavenly shafts of light. Not for Rembrandt. Other people in the scene are doing things ordinary people do. Some are listening to him, but others aren’t paying attention at all and are talking among themselves. A scrawny dog is hoping for scraps of food at the feet of the woman with children. On the far right, a camel driver looks bored and tired as he rests his head on the camel. The point: sometimes when a gifted teacher is speaking, some people are paying attention, but others are not.

Coming back to our theme: if Jesus channels the “love of God,” it’s not a one-size-fits-all warm and gentle feeling, like we have when we see a photo of a puppy. Far from it. For the characters in this etching, the love of God is customized for each person, directed at what they need in that moment in their life. For some it’s healing, comfort and blessing. For others, it’s challenging righteous assumptions, posing provocative questions, or causing them to discern their true motivations.

Looking back on my life, this expresses how I’ve experienced divine love and leading.

Many times, I’ve reached out in a time of need and been given “a peace that surpasses all understanding.” Sometimes that came right away, sometimes it came later in the day, sometimes several days later. But when it came, I felt cared for. I know many others have this experience.

Other times I’ve reached out for guidance, I was really hoping I’d find some pleasant reassurance or an easy way out. And instead, I was given something better.

In 1986, my wife and I had spent a year as volunteers at The Campbell Farm, an apple farm and retreat center within the Yakima Reservation in rural Washington. I had never lived in an area with a high poverty rate. I thought we’d be there for a short time, then move on to some setting where life was easier. The local church had offered me a position as pastor, but I was reluctant to stay. I prayed for guidance. One afternoon, I was out in the alfalfa field changing irrigation lines. These words appeared in my awareness: “Instead of being served, think of serving.” After a moment of reflection, I knew what that meant. I didn’t like it. But I sensed I needed to trust that message. I accepted the call. We ended up staying for six years. It was not an easy time, but a rich and rewarding time as I learned about myself and rural communities and served as best I could. I’m forever grateful my ego was confronted rather than appeased. Looking back, it was a message I needed to hear.

Divine love can be a combination of care and confrontation. That’s one of the many reasons grace is amazing.

— Steve

(For a full view of the 100 Guilder Print, go to https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Rembrandt_The_Hundred_Guilder_Print.jpg/1280px-Rembrandt_The_Hundred_Guilder_Print.jpg)

#/media/File:Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_Children’s_Games_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)