This month we have been spending time in the mountains…first the Sierras and now near Mt. Shasta. I’m not doing any writing, but will share a few photos.

I hope you are finding moments of rest and reverence.

An offering of spiritual insights and epiphanies.

This month we have been spending time in the mountains…first the Sierras and now near Mt. Shasta. I’m not doing any writing, but will share a few photos.

I hope you are finding moments of rest and reverence.

In the last years of his life, the French Impressionist painter Jean Renoir continued to paint despite intense pain and physical limitations from rheumatoid arthritis. At one point he said: “Pain passes, but the beauty remains.”[i]

His pain ended with his death, but the beauty of his work lives.

I’ve participated in many memorial services in my life. In such times we have a deep instinct to look for the best in someone’s life, which we hope will transcend whatever pain they endured. If the person has been able to live a full and meaningful life, this can be easy. But if the person’s life was marked by tragedy, the desire to focus only on the positive can feel inauthentic — perhaps a way to avoid our own pain and doubts.

This week I spoke at a memorial service for a man who died in his late 80s. He’d gone in for a heart procedure that was intended to give him several more years of vitality. But things happen, and he died at the hospital. Yet at the service, we reviewed the span of his life, the legacy of his love, and the many joys he knew; all this was far more important than the way he died.

This week I also knew a person whose life was drawing to its completion. She had a life of many adventures and much love, but this last year was marked by personal tragedy. I don’t want to look away from the tragic elements, but I see even more clearly the splendor of her life.

From the pain, I want to learn empathy and compassion.

From the beauty, I want to practice awe and reverence.

Perhaps this drive for transcending suffering is ingrained in life.

A friend who is vacationing in the Caribbean posted some photos this week and commented: “I took a walk on the beach in Barbados tonight and found four turtles coming to shore to lay eggs. I spent about an hour watching one come out of the surf, on to shore and then digging a hole to lay eggs. Incredible.”

Patience. Endurance. Hope. Don’t we all wish this for ourselves and for others: “Pain passes, but the beauty remains?”

Lead image: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Self-portrait, 1899, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, USA.

At 7:30 AM this past Wednesday, I picked up my 6- and 9-year-old grandsons to play golf at our local 9-hole course. Our custom is to rent a cart, tee up, and embark on our adventure. We celebrate our best shots but don’t keep score.

Near the green on the 5th hole, the 9-year-old said, “There’s a frog!” He pointed to the ground, but I couldn’t see what he was talking about. He knelt down, carefully picked up a wee creature, cupped it in his hand and showed us. It was an exciting discovery:

We continued to play, but the kids’ attention was focused on the frog. They decided to name it “Fred.” The six-year-old decided to not play the next two holes so he could be Fred’s primary guardian. On the last two holes, they took turns: one would be Fred’s caretaker while the other took his shot.

We finished our round and went to breakfast. Before going into the restaurant, they designed a minimum-security safe space for Fred in the cupholder of the car console, using a napkin as the roof.

After breakfast we came out and discovered Fred had escaped. I happened to see him by my right foot next to the accelerator pedal. I moved my foot aside. The 6-year-old rose from the back seat and twisted himself past me for the rescue, his feet in the air like a descending abalone diver. He gently placed Fred in the palm of his left hand and returned to his seat.

A few minutes later, we pulled into their driveway. The boys quickly got out and took Fred inside, leaving me behind to bring in the leftover French Toast and the unfinished blue Poweraide. They rushed past their mom to their bedroom, formulating plans for a suitable enclosure that would keep Fred safe until he’d be released into the nearby creek.

Fred is not a digital representation of a frog. He’s not a character in a video game. He is not an imaginary creature created by artificial intelligence that looks and acts like a frog. Fred is real. If you aren’t careful, you can hurt him. He’s a marvelous work and a wonder. He honorably represents the countless frogs, tadpoles, grasshoppers, ladybugs, Roly Poly Bugs, and other creatures that children have been discovering, learning from, and caring for as long as human beings have been inhabiting this earth.

Who was I to think that the most memorable event of the day might be some remarkable shot from grandpa?

I led many a meeting over the years. If it was a new group, I would often begin with a question for everyone to answer. The one I used most often was, “Where did you grow up, and what did you like best about it?”

I’d wait a minute or two, then offer my own response as an example. “I grew up in San Bernardino, California. What I liked best about it was our neighborhood. It was at the base of the foothills and there were lots of kids on our street. We spent countless hours getting together to play games like hide and seek, cops and robbers and whatever sport was in season.”

Then others would respond.

“Every summer we’d go back to our grandparents farm for a month.”

“We had a cabin by a lake, and we’d go there for our vacation. We had every day free to hike, fish, and play games.”

“In my neighborhood, there was a big vacant lot at the end of the street, and the neighborhood kids would meet there every day and come up with something to do.”

Over time, I saw two common themes.

This came to mind as I read a recent article in the New York Times, “Racing to Retake a Beloved Trip, Before Dementia Takes Everything,” by Francesca Mari.[i] It’s a personal story about her journey with her 72-year-old father who has advancing dementia. He lives alone in Half Moon Bay, and she teaches at Brown University in Rhode Island. Mari’s mother died when she was 10. Her father never remarried, and she is an only child. She describes the challenges of caring for a parent with dementia. Before it gets worse, she decides to take him to Switzerland and Italy, retracing a trip he had with his parents when he was 14 as they visited the village of his grandparents. She hoped this might be a positive experience for them both.

This is a well-told-tale, and I will not try to retell it. Suffice it to say that, despite many challenges, they find his family’s ancestral home in a small Swiss village. Along the way, listening to Beatles’ music in the car and seeing new sights, her father summons up many warm memories, many which she has never heard before. In some ways, he comes alive again. Interspersed with their adventures and discoveries, Mari shares insights about the power of nostalgia and reminiscing:

In the 1950s, the tendency of old people to reminisce was thought to be a sign of senility. The first long-term studies of healthy elderly people began at Duke University and the National Institutes of Health’s Laboratory of Clinical Science only in 1955 — and it wasn’t until the early 1960s that Robert Butler, a psychologist then at the National Institutes of Health, realized that nostalgia and reminiscence were part of a natural healing process. “The life review,” as Butler came to call it, “represents one of the underlying human capacities on which all psychotherapy depends.” The goals of life review included the righting of old wrongs, atoning for past actions or inactions, reconciling with estranged family members or friends, accepting your mortality, taking pride in accomplishment and embracing a feeling of having done your best. Interestingly, Butler noted that people often return to their birthplace for a final visit.

Butler believed life reviews weren’t the unvarnished truth but rather the reconciled one, more like the authorized biography. The edited narrative is born of psychological necessity. “People who embark on a life review are making a perilous passage,” Butler wrote, “and they need support that is caring and nonjudgmental. Some people revise their stories until the end, altering and embellishing in an attempt to make things better. Pointing out the inconsistencies serves no useful purpose and, indeed, may cut off the life-review process.”

…. memories must travel between people. Without pollination, they wither. Families collectively remember, they maintain narratives, fill them in and round them out and keep people close long after they’ve left…

I remember listening to my father reminisce in his later years. My mother died 20 years before he did. Growing up, my siblings and I remember many good times, as well as the ways in which they frustrated each other. But as time went on, dad’s retellings did not include any reference to their differences. Instead, he only saw her in the light of the love he had for her. Who were we to correct him?

I have been fortunate to spend a great deal of time listening to older peoples’ memories, stories, and lessons they’ve learned. Now that I am a Medicare-card-carrying-member of this age group, I understand the desire to try to make sense of the lives we’ve lived.

In April, I went back to my hometown to visit the cemetery where my ancestors are buried, including ones who died before I was born. There was nothing there but gravestones, but something led me to kneel, touch the marker, and thank them.

There is a famous phrase of Shakespeare’s, which, as I discovered, opens his 40th sonnet:

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought…

The poem continues with verses describing grieving lost friends, then ends with:

But if the while I think on thee, dear friend,

All losses are restor’d, and sorrows end.

May we be willing to honor those who reminisce and be grateful for the friends and families with whom we can “pollinate” our fleeting memories.

[i] “Racing to Retake a Beloved Trip, Before Dementia Takes Everything” (If you cannot open the article but want to read it, email me and I’ll send you a PDF copy.)

Photo: The village of Treggia, Switzerland, where the author’s grandfather was born

Some people love hot sauce, the spicier the better. Others like it mild. Others want none at all. Are these preferences the result of a logical thought process, or simply an honest report on what peoples’ taste buds tell them?

When we make judgments about other people, moral questions, and politics, is it our thinking mind that decides what’s true? Or is it more often a deep feeling/reaction we have, and our thinking mind comes up with reasons to support that point of view?

When a human rider is on top of an elephant, which one holds the real power to decide what direction to go?

Several years ago, I read a book which challenged my understanding of the way we make judgments: The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt. Haidt draws on extensive research about moral reasoning and comes to many important conclusions. One of them employs the metaphor of an elephant and its rider. In this imaginary scenario, the rider does not ultimately decide which path the elephant takes, but, in many ways, is “along for the ride.” The rider’s job is to come up with reasons to justify which way the elephant wants to go. Haidt says our moral judgments are like taste buds — more a reflections of our instincts and intuition than a logical process. This explains why people across cultures, in religion and politics, fall into groups often labeled “liberal” and “conservative;” people may look at the same set of facts or events but draw different conclusions.

This explains why we hear people say, “How can they think like that? Why won’t they listen to reason and pay attention to the facts?

I grew up in a racist culture. I didn’t realize it at the time – I just thought this was the way life was. My view of African Americans came from all directions…comments, jokes, a biased history, commonly accepted racial slurs, and TV shows like “Amos and Andy.” I didn’t think this was point of view was right, it was just the way it was. As I got to know African Americans in school, in the workplace, and through our evolving culture, my views changed. Personal experiences and compelling stories began to challenge my inherited bias. My elephant began to go in a different direction, and my rider-mind began to understand the world differently.

I grew up in a homophobic culture which has undergone a similar evolution.

After 9/11, I became involved with community interfaith groups that included Muslim and Jewish representatives. I led a year-long project in which a dozen people from my congregation as well as a dozen from the local synagogue and mosque began meeting every other week for lunch. In the early meetings, we did not talk about our different beliefs, but focused on getting to know each other as human beings. We learned about each other’s families, life stories, hopes and dreams. In the early encounters, my elephant kept tugging at me, saying “This person is fundamentally different than you.” But over time that changed; the categories I had inherited faded, and I saw each participant as a unique individual.

Looking back, it is interesting to see how the change in my unconscious elephant came about through accumulated visual impressions and how they were tied to judgements. Before the project began, if I saw a woman wearing a hijab face covering, the only realities I could associate with that were the endless news stories about terrorists and the oppression of women; such stories were always accompanied with suspenseful, troubling music. So, when I first met some of the Muslim women, I felt tense. But over time, as I got to know them, I no longer noticed how they dressed or if they had a face covering — I knew them as friends. After the project ended, I was traveling to Ghana and had just boarded a plane at JFK airport. I saw five Muslim women coming down the aisle. My “elephant” said, “Oh, look, some Muslim women…I’d love to get to know them!” In that instant, I realized my snap judgment had totally shifted because of our project. The change came about not by rational persuasion as much as lived experience.

I currently live in a community that votes very “blue.” Before coming here, I lived in a community that was politically “red.” I have friends who hold differing perspectives in both communities, and I can tell you what life experiences has led them to see things the way they do.

As we approach the 4th of July, we will be reminded of the words ““We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” For decades, “all men” meant “all white males” – that was the elephant the leaders were riding at the time. But through much suffering and striving, we’ve come to realize that the more profound and inspired meaning is not “all white men” but “all people.” America at its best is not about the dominance of one ethnic group, but a shared dream for the entire human family.

Our spiritual traditions were born in cultures with their own sense of tribalism, identity, and biases. But at their best, they call us to go beyond the brute instincts and assumptions we ride on. They call us to see all people as created in the divine image, regardless of ethnicity, gender, and social status. Through powerful teachings and stories, our “riders” can sometimes convince our “elephants” to move towards higher ground. Our progress may be slow and the obstacles never ending, but the ethical summons and divine vision is nonnegotiable.

Lead image: https///usustatesman.com

Lower Image: elephant_and_rider_by_ohmygodfatherscat_d1oxikr-fullview.jpg

I came across an article on the business philosophy of Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon:

Company data showed that most employees became less eager over time, he said, and Mr. Bezos believed that people were inherently lazy. “What he would say is that our nature as humans is to expend as little energy as possible to get what we want or need,” Mr. Niekerk said. That conviction was embedded throughout the business, from the ease of instant ordering to the pervasive use of data to get the most out of employees.[i]

Apparently, Amazon is built on the conviction that we are “inherently lazy.” While sitting at my desk on a summer day, surrounded by books I’d ordered on Amazon, I decided to explore what “lazy” means.

One definition is from Dictionary.com: 1) tending to avoid work, activity, or exertion: “She was too lazy to take out the trash, so it just continued to pile up;” 2) causing or characterized by idleness or inactivity: “I’m having a lazy day today, just lounging and watching movies…”

Looking for the origin of the word, I found: The adjective lazy is thought to come from the Low German lasich, meaning “idle or languid.” Ex: “You were offended at being called lazy, but you just didn’t have the energy to defend yourself.”[ii]

Another source says that to be lazy means you just “…can’t find a reason to make any effort.[iii]

I thought about phrases that include “lazy,” like “lazy bum.” And how about “Lazy good-for-nothing?” One source says this means: “having no ambition, success, or value to society… (for example)” he refused to leave anything in his will to his good-for-nothing grandchildren.”[iv]

So, signs that we are lazy would include not taking out the trash, watching movies all day, not having the energy to dispute someone who calls you lazy, not caring if you are doing nothing, and not getting any money from grandpa.

2,500 years before Mr. Bezos started his business, the Book of Proverbs had its own perspective:

So, in ancient days, signs that you are lazy include recognizing a need to look to ants for inspiration, being useless to your employer, and feeling it’s too much work to feed yourself.

It didn’t get any better in the Middle Ages: one of the Seven Deadly Sins was acedia, which means “without care.” In modern English, we call it sloth, a kind of slur on the slow moving South American mammal who spends the day hanging upside from trees.

But the more I sat in my chair and pondered all this, I discovered being lazy isn’t all bad.

In the 1920s, some businessmen in Monroe, Michigan designed an ideal chair in which people could relax. They held a contest to come up with a good name. The result was the “La-Z-Boy” chair.[v] We have two in our living room.

Who, sitting at a table and desiring a condiment, wants to stand up and reach for it? The solution is a Lazy Susan – just give Susan a spin and she brings the olives right to you. (This is not meant as a slight on anyone named Susan.)

Here’s a positive perspective: “Former President of Poland Lech Walesa once considered the benefits of being lazy when he said, “It’s the lazy people who invented the wheel and the bicycle because they didn’t like walking or carrying things.”[vi]

So, clearly, being lazy is good for Amazon, furniture manufacturers, listless dinner guests, and people who design bicycles.

But most sources would say being lazy is not a virtue to cultivate or encourage. One should instead pursue the art of “resting.”

Going back to the Bible, the fourth Commandment says: “Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work. But the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any work… (Exodus 20:8-10) Taking at least one day off every week becomes one of the blessings humanity is encouraged to claim. Doing so is not a waste of time, but instead helps us replenish our energy and cultivate a reverence for the gift of life.

Why exactly is resting a good thing and being lazy is not?

The distinction seems to lie in what our motivation is. Have we fulfilled our responsibilities and would benefit from taking a break to find fresh energy before returning to them? That’s called “rest.” But if we are lying around to avoid what needs to be done, that’s being “lazy.”

I thought about developing this idea further, seeking a more profound perspective, but decided not to. Instead, I’m going to go outside – beyond the reach of Amazon — put my lounge chair in the shade and relax. I won’t be idle, though; I plan to think about ants.

Images:

Sloth photo, “42 Slow Facts About Sloths,” factinate.com

“The Seven Deadly Sins: Acedia,” Hieronymus Bosch, c, 1500

Chair: Platinum Luxury Lift® PowerReclineXR+ with Power Tilt Headrest and Lumbar

[i] Bezos says people are lazy

[ii] https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/lazy

[iii] https://www.quizexpo.com/am-i-lazy-quiz/

[iv] https://www.merriam-webster.com/thesaurus/good-for-nothing?pronunciation&lang=en_us&dir=g&file=goodfo01

We live life within the stories we create about ourselves. But, unlike testimony we give in a court of law, we can change our stories if we choose.

In a writing workshop, Marilyn McEntyre encouraged us to revise our life stories as often as needed. She points out that the original meaning of “re-vise” is to “look at again, visit again, look back on.” [i] She encourages anyone (including the people with serious illnesses whom she works with), to not get stuck in our old narratives. You are the author of your life, she says. Events beyond your control may impact you, but you’re free to decide how you will respond, what role you will play, and who you become.

Thinking about this reminds me of similar insights I’ve heard over the years.

In a blog post two years ago, I shared a comment attributed to Jonas Salk, the creator of the polio vaccine. When asked what had enabled him to become a successful experimental scientist, he credited his parents. If he would spill milk in the kitchen, Salk said, they would not get angry with him. Instead, they’d ask, “What did you learn from that?” This perspective guided Salk in his scientific career, encouraging him to not be afraid to try things. If we make a mistake, we can re-visit the experience, see what we can learn from it, and decide what to do differently next time.

I have also shared a comment Parker Palmer made about the term “disillusionment.” When we say we have become disillusioned, we often say it with a sense of sorrow or defeat. But, he said, think of what the word means: to be dis-illusioned means we realize we had an illusion and it’s been “dissed.” Instead of feeling discouraged, imagine we’ve been liberated from mistaken assumptions, open to a clearer sense of the truth.

Looking back on my life, there have been times when I have trusted some people too soon and too much. When I eventually recognized it, I felt frustration for having been naïve. But I can “re-visit” the experience and accept I was the one who created the “illusion” of what to expect. I can be grateful my illusion has been dissed, and plan to be more careful next time. (I’m still working on this.)

I remember a hospice study in which a medical team examined why some people die in misery and others — with the same illness — die with a sense of peace. One of the factors they identified was “Experience of a sympathetic, nonadversarial connection to the disease process.”[ii] I can see cancer as a dark, malignant force that is attacking me as a personal aggressive act; if it “wins,” I have not only lost my health but been humiliated and defeated. But I can see it from a different perspective: cancer is a common occurrence with living beings and there’s nothing personal about it. I will still do all I can to send it into remission, but cancer doesn’t define who I am as a person, nor will it ever be able to harm my spiritual essence which will survive death. It’s not easy to navigate this process, but I have seen people “re-vise” their understanding of life and illness and find a sense of peace. A new perspective is powerful medicine.

A common teaching in the spiritual traditions is to be honest about our short-comings and mistakes, but not be bound by them. Instead, we accept the grace, compassion and forgiveness that comes from a source beyond our egos while remaining thoughtful about our own behavior. Re-vising our life stories does not mean we are avoiding or denying the facts of what happened; instead, we are finding a fresh perspective that can empower rather than diminish us.

[i] https://www.etymonline.com/word/revise

[ii] “Healing Connections: On Moving from Suffering to a Sense of Well-Being,” Balfour Mount, MD,Patricia Boston, PhD, and S. Robin Cohen, PhD; Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, April 2007 (Other factors named in the study: “Sense of connection to Self, others, phenomenal world, ultimate meaning; Sense of meaning in context of suffering; Capacity to find peace in present moment; Ability to choose attitude to adversity; open to potential in the moment greater than need for control)

Marilyn’s publications and workshops, including her work with people dealing with illnesses, can be found at MarilynMcEntyre.

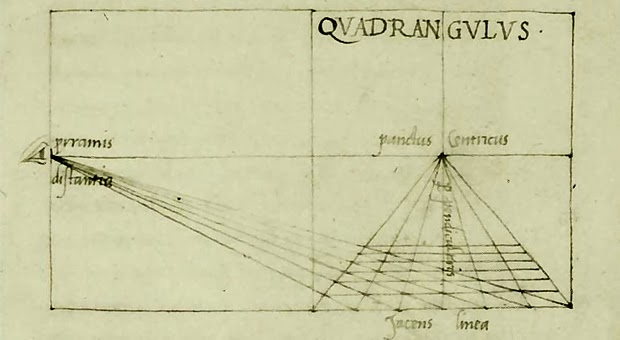

Lead Image: “A Lady Writing,” Vermeer, 1665, National Gallery of Art; lower image: “Quadrangulus,” Milra Artist Tools, LLC

In a season when many young people are hearing commencement speeches, I was intrigued by a recent column: “’Follow Your Dreams’ and Other Terrible Career Advice.”

The writer is Bonnie Hammer, an executive at NBC Universal. She begins by acknowledging that many young people find work is not as rewarding as they had expected. Here are some excerpts:

Having worked in most facets of the entertainment industry since 1974, from a bottom-rung production assistant to the top of NBCUniversal’s headquarters at 30 Rock, I agree that the problems in today’s workplace are real. But I also think many management experts have identified the wrong problem. The real problem is that too many of us, young and not so young, have been told too many lies about what it takes to succeed at work—and not nearly enough truths. All those bright, shiny aphorisms that are spoon-fed to young employees, like “follow your dreams” and “know your worth” and many more? Well, the truth is that they don’t really work at work…

“Follow your dreams” is the exhortation of many college commencement speeches, but it is nightmare job advice. Americans are already raised on a diet high in dreams, from fairy tales to superheroes…

The larger truth is that professional dreams can be incredibly limiting, particularly at the start of our work lives. When we enter the workplace convinced that we already know what we want to do in a specific field and are committed to it at all costs, we’re saying, in essence, that there is very little left for us to learn, discover or be curious about. That nothing else could make us happy or fulfilled…

…I learned my “workplace worth” fresh out of graduate school when I was hired as a production assistant on a kids’ TV show in Boston. Each PA was assigned a cast member, and as the most junior employee, my cast member was Winston, an English sheepdog. My primary responsibility was to follow him around the set carrying a pooper scooper. I had two university degrees. Winston, on the other hand, was a true nepo-baby, the precious, unhouse-trained pet of one of the show’s producers. Plus, as an on-camera star, Winston out-earned me…

…But while many days I felt like working for Winston was beneath me, I never showed it. I acted like I was pursuing an honors degree in pet sitting, and each poop pickup was an extra-credit opportunity. The work and the attitude paid off. When an associate producer position opened, I was promoted. I pursued a similar strategy for much of my early career: If I wanted to be a valuable asset to my colleagues and bosses, I knew I needed to add concrete value to their days by showing up, staying late and doing whatever needed to be done. So maybe we need to set aside the current myth that remaking the workplace will somehow unleash a wave of professional success. Instead, it might be time for a healthy dose of truth. For young employees who want to feel “engaged” at work, the truth is, you need to engage with your work first. On the job, our worth is determined not by how we feel but by what we do.

… Looking back, I was only able to work my way up to the top because I started at the very, very bottom. Not only did this starting point allow me the opportunity to really understand the TV and entertainment world, but I also had real empathy and appreciation for the people now doing the work I once did.[i]

I think of the many times someone receives an Oscar, or wins a sports championship, or has become successful in the arts or business, and they say something like, “This is my dream come true! For all you out there with a dream, don’t give up!” That passionate plea may motivate others to achieve “greatness.” But for most of us, despite hard work and discipline, we may never “succeed” like we thought we would when we were younger.

I dreamed I was going to play shortstop for the Dodgers. Then I dreamed I would be a millionaire lawyer in San Francisco. Then I dreamed with just a little effort I could speak four languages. I had some dreams. But I didn’t know how much hard work, focus, stamina, and good luck it can take to realize lofty dreams. It was a big disappointment.

But along the way, I discovered that I could still enjoy sports without being a star. I could enjoy being in a city without being a millionaire. I could have empathy for someone from another country struggling to speak English. I experienced many blessings that I could not have dreamed of when I was young.

Life has a way of showing us our limitations. It also can teach us that “it’s not about me.” We can find a kinship working with and serving people who aren’t superstars. Our youthful dreams may disappear, but we may find we can appreciate life without being in the spotlight.

Ms. Hammer says she has “reached the top.” I have met some people who have “made it to the top” and been able to keep their humanity and integrity. I know others who have been consumed by work and dreams of success and are blind to other sources of meaning and purpose. “What does it profit a person to gain the whole world and lose their soul?”[ii]

Dreams about who we can become and what we might accomplish can serve an important purpose: they can motivate us to see what we are capable of. But if it doesn’t work out as we had hoped, it doesn’t have to be the end of the world. It may be the beginning of finding something more lasting and rewarding: a deeper connection to the human family and purposes larger than ourselves.

(Note to readers: Some of you have told me you’ve tried to make comments but had issues with the website. You can always email me directly at steve@drjsb.com)

[i] ‘Follow Your Dreams’ and Other Terrible Career Advice (WSJ, May 4, 2024)

[ii] Mark 8:36

This is my friend Gracie. She is a red wiggler worm that lives in our compost bin. She’s a hard worker and important part of our household. Recently I’ve been telling her what she does is a rich metaphor for the spiritual power of grace. I asked her if I could tell you her story. She agreed but wants you to know that all the spiritual talk is not her idea, but stuff I’ve made up.

Her story begins seventeen years ago when I decided to explore organic gardening. I read articles and attended classes. I planted a variety of heirloom tomatoes. I experimented with lettuces, beans and peas. And I created my first worm composting bin. I don’t do much gardening anymore, but I’ve stuck with the worms.

Let me tell you why Gracie and her clan are so amazing:

Here’s a photo of Gracie’s Clan at work:

Now we can turn to the spiritual meaning of composting worms.

When I talk about grace here, I’m thinking of the divine spiritual force known as agape, which transcends all our pettiness; it simultaneously humbles us and fills us with a quiet joy. I’m also thinking of the Buddhist concept of deep compassion, which can help us see, accept and deal with whatever comes our way.

The way spiritual grace works is that it can take all the stuff of your life – the good decisions and the bad, the traits you like about yourself and those you don’t, your victories and defeats – and turn it all into something useful and positive.

There is a legend that St. Francis offered sermons to the birds, and they listened attentively. I tell Gracie all the ways in which I think she symbolizes grace, but I don’t think she’s listening. She’s too busy making all things new.

For a more detailed explanation of what Gracie’s Clan is about, go to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vermicompost

It took me a minute to get the point of this recent New Yorker cover:

…eventually, I figured it out: the cat is immersed in chasing the animated mice in the video game on the tablet. In the background, real mice are having a party. “When the cat’s away, the mice will play.” The cat’s body is not “away” – it’s in the same physical space as the mice — but its attention is not there; it’s captivated by the screen.

Everywhere we turn, people’s attention is on their screens instead of their immediate surroundings. Brilliantly designed digital clickbait has become our culture’s catnip.

My thoughts turn to one of my favorite paintings, “Children’s Games” (Brueghel, 1560):

As I noted in a post three years ago,[i] there are 80 different games portrayed here: playing with dolls, shooting water guns, wearing masks, climbing a fence, doing a handstand, Blind Man’s Bluff, making soap bubbles, walking on stilts, riding a hobby horse made from a stick, playing with balloons (before latex, made from a pig’s bladder), catching insects, climbing a tree, and 68 others. This was almost 500 years ago — before electricity, the microchip, Big Tech, and AI. Kids left alone and unplugged find things and create.

A current bestseller is The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt. Haidt shows how the advent of the digital age has led to increasing isolation among teenagers, which in turn has contributed to a rise in depression and suicide. He notes that many of the tech innovators in Silicon Valley restrict their own children’s screentime, then lead business ventures that will profit from making screens even more addictive. Haidt encourages families and schools to restrict screentime and instead let kids be on their own more often to find out how real life works. He founded “Let Grow,” an organization creating resources for families and schools to nurture kids’ character and self-reliance.

Two afternoons a week we care for our grandsons, ages 6 and 8. They come to our house after school and have a snack. We let them watch 20 minutes of a favorite show (currently a guide to building more complex “Minecraft” structures on their tablets). Then we turn the television off and discuss what’s next: board games, crafts, gardening, or some sport.

Recently my wife had to take the 8-year-old to an early baseball practice, so I had 45 minutes with the 6-year-old. We went out into the backyard to hit whiffle balls. We used to have ten plastic balls, but as the boys have gotten stronger, their hitting prowess has led to nine being lost over the fence and elsewhere. We started playing with the last one, the old savvy veteran pitching tossing to the promising rookie. Soon the ball disappeared over the neighbor’s fence. But I found a partially cracked plastic golf ball buried in the bushes. I asked if he wanted to see if he could hit it. He liked the challenge and got some great whacks. In the process, the crack expanded. We were sure one more solid hit would split it in two. But the time came for me to take him home. Last seen, the little broken ball had fled into the bushes to survive for another day.

We had just spent 20 minutes playing with a whiffle bat and a broken plastic golf ball. What we did was not planned or packaged. It was improvised. It was fun. It was physical and mental. Our bodies, attention, and minds were all present in real time, interacting with each other and the surrounding environment.

Tech marches on. I look forward to the good things that may come our way (maybe from future engineers who became masters at Minecraft). But I worry every day about where AI is going to take our attention. We think we are smart, but tech is getting smarter. I am a constant advocate for putting limits on tech. This week I signed up with “Let Grow” to follow what they are doing. I want to see more kids hitting balls with sticks.

(The bashed-up plastic golf ball may be hiding in this plant.)

[i] The previous post in which I featured Brueghel’s painting is at https://wordpress.com/post/drjsb.com/376

For a more detailed study of “Children’s Games,” go to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Children%27s_Games_(Bruegel)