I sometimes find myself wondering if life is all about creating memorable “highlight reels.”

Highlight reels are excerpts from sporting events that capture dramatic and decisive moments. You don’t have to watch the entire World Cup soccer game to find out it ends in a scoreless tie – you just watch a few minutes of compelling footage that an editor has decided will hold your attention. You don’t have to sit in the stands at a baseball game for 3 ½ hours as it painstakingly unfolds – you just see 5 minutes that include the diving catch, the dramatic home run, and the last guy striking out. The folks who put the highlight reels together know how the game turned out, so they can create just the right script and a satisfying finish. The scenes include commentary by a skilled announcer and maybe even a dramatic soundtrack. Highlight reels can be much more engaging than the actual experience.

In this digital age, we can make our own “highlight reels” using our smartphone cameras. We can capture stunning sunsets, joyous birthday cake moments, and two friends smiling at the foot of a majestic waterfall — significant moments of inspiration, celebration, and affection. That’s what we want to remember. Who wants to watch real-time video of the drudgery we felt at work before we got home to see the sunset, the housework we had to do to get ready for the party, or the long hike that got us to the waterfall?

And in recent years, it’s common for memorial services to include a slideshow of the person’s life, tracing it through the decades with carefully chosen images. It’s always moving to feel like we are seeing pictures that each tell us a thousand words about someone’s life, especially when we know their life is complete.

So I sometimes wonder: maybe it’s only life’s highlights that are worth living for.

But then I consider the oak tree in our backyard.

The oak tree in our backyard (as seen in the above photo) is a “volunteer,” meaning it came up out of the ground unexpectedly. I remember first seeing the 18” sprout while doing yard work; I had a pair of pruning loppers, assumed it was unwanted, and was ready to snip it into oblivion. But my wife saw me and said, “Don’t cut it! That’s a volunteer oak. Leave it alone. Let’s see how it grows.”

Years later it’s a magnificent living presence. Our landscape designer is in awe of its structure and vitality. He told me the tap root can go 100’ feet into the earth, and that a wealthy person would pay $50,000 for a tree that looks like this one.

I find myself gazing at this tree and thinking how undramatic it is, how silent, how steady, how patient. It’s alive. It grows. It simultaneously knows how to send roots into the earth seeking water while sending branches into the sky seeking light, all the while breathing in carbon dioxide, breathing out oxygen, and manufacturing acorns to provide for future generations.

If I was to make a “highlight reel” of the oak tree, what images would I use? It does all its labor undercover. Meanwhile, I rush through my days hoping to do something that will qualify for my personal highlight reel.

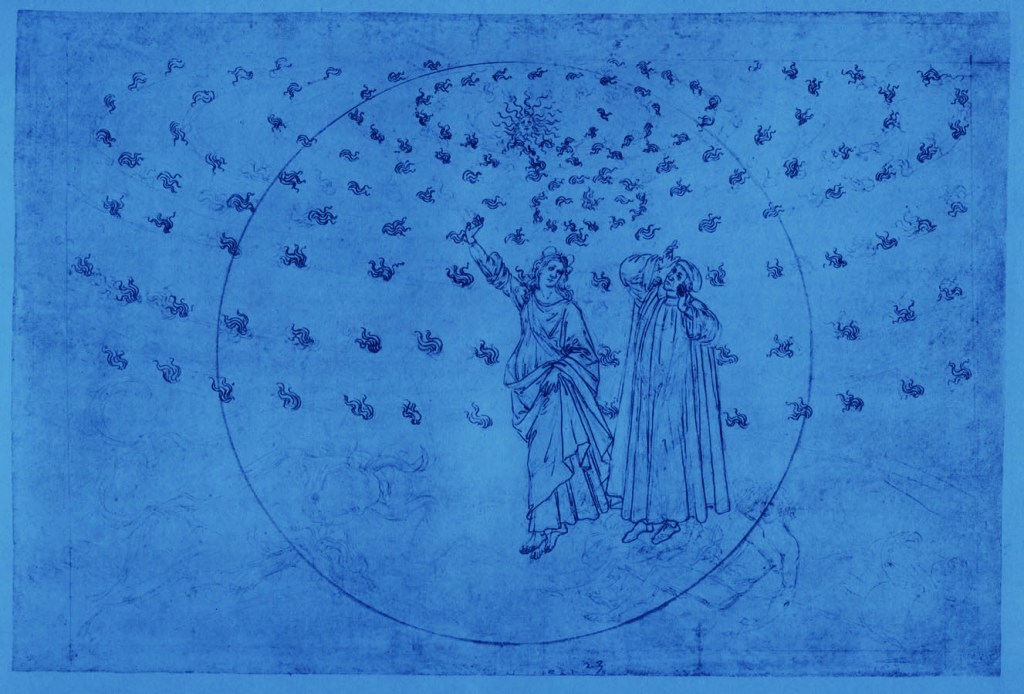

Trees are prominent in spiritual traditions. The “Oaks of Mamre” is a place of divine encounters for Abraham.[i] Though they have never met before, Jesus tells Nathaniel he already knows him because “I saw you under the fig tree.”[ii] And, according to one tradition, Buddha sits for 49 days under the Bodhi tree, stands to thank it for its shade – and in that moment receives enlightenment.[iii]

Trees are a common source of shelter and safety, and therefore an ideal place for contemplation. But maybe there’s more to it than just protection from the sun. Maybe being in the presence of such creations subtly reminds us that life is more than just clips that qualify for a highlight reel. Maybe they instead teach us what it is like to be quietly immersed, moment-by-moment, in the miracle of life.

[i] Genesis 18:1

[ii] John 1:48