I recently read a review of a new book, Imperfection, by an Italian biologist, Telmo Pievani.[i] The theme is that some people expect nature to be “perfect,” but in fact, from the Big Bang to the present moment, imperfection permeates life:

- “In the beginning, there was imperfection. A rebellion against the established order, with no witnesses, in the heart of the darkest of nights. Something in the symmetry broke down 13.82 billion years ago.”

- “Mary Poppins congratulated herself for being ‘practically perfect in every way,’ but of course she wasn’t, if only because she bragged about it.”

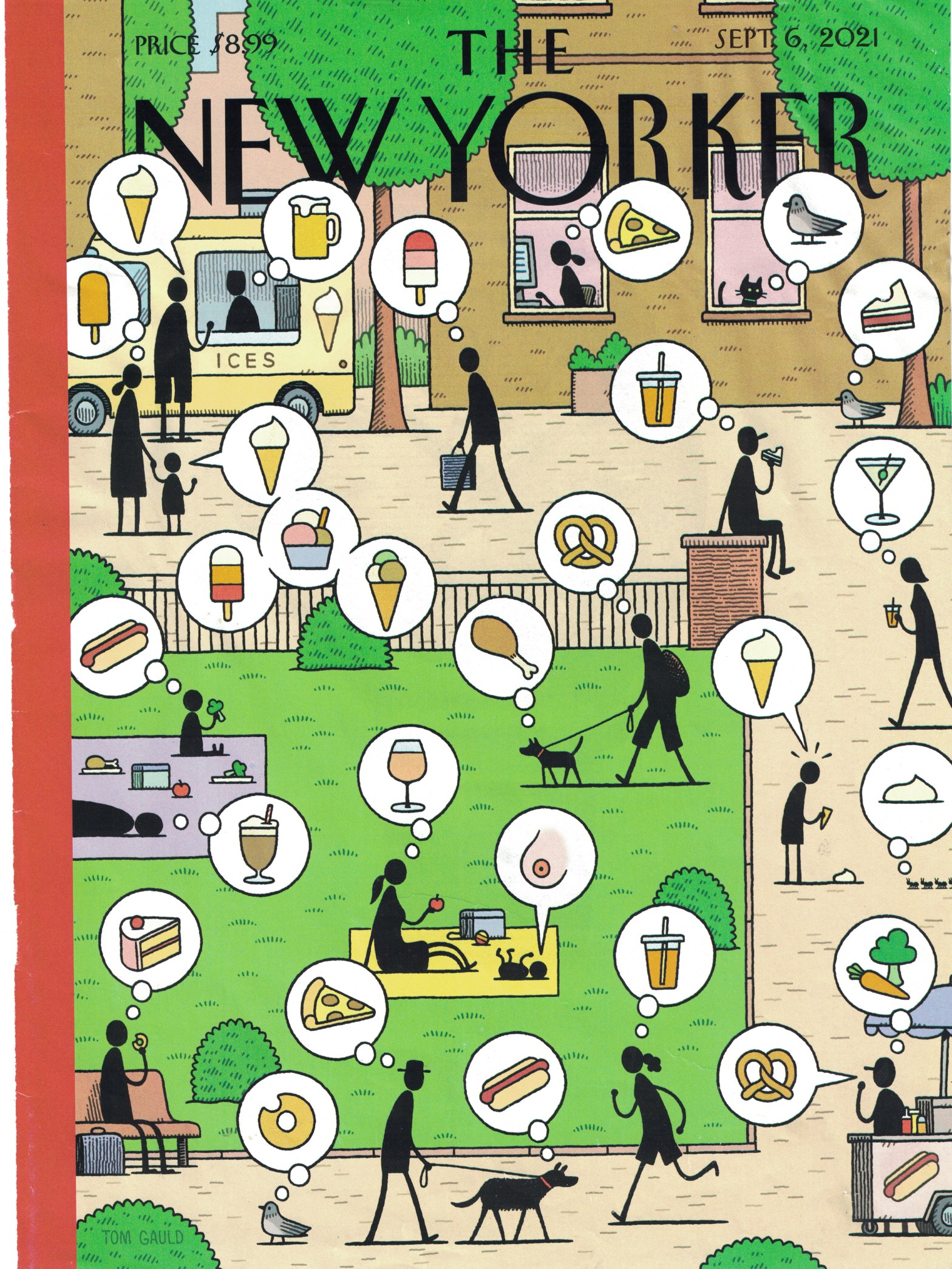

- “… being primates, our Pleistocene ancestors were naturally fond of sugars, which indicate ripe fruit, and of fats, present—albeit in generally small quantities—in game. Today, our culture provides us with excessive opportunities to indulge such fondness, which we overdo, benefiting only the confectionery and meat industries, along with dentists, cardiologists and morticians.”

- …”Homo sapiens are marvels of unintelligent design, with their useless earlobes, their tedious wisdom teeth . . . the remains of their ancestral quadrupedal gait, and the corresponding ills and pains, backache, sciatica, flat feet, scoliosis, and hernias. Add the terrible structure of our knees, our lower backs…”

- “Imperfection makes clear that ‘evolution is not perfect but is rather the result of unstable and precarious compromises,’ and that accordingly it isn’t a highway to excellence but a bumpy path that, despite potholes and construction delays, leads at least some travelers to the biological goal of survival and reproduction.”

- “Readers wanting to get up to speed on imperfection would do well to attend to two little-known words with large consequences. The first is “palimpsest,” which in archaeology refers to any object that has been written upon, then erased, then written over again (sometimes many times), but with traces of the earlier writings still faintly visible. Every living thing is an evolutionary palimpsest, with adaptations necessarily limited because they’re built upon previous structures.” As a prime example, the author notes that we’ve evolved to have big heads, but the birth canal passes through the pelvis. This worked well when our ancestors had small heads but increasingly is a problem with our increasing hat size.

- “Which brings us to our second unusual word: ‘kluge,’ something—assembled from diverse components—that shouldn’t work, but does. A kluge is a workaround: often clumsy, inelegant, inefficient, but that does its job nonetheless. Because we and all other living things are living palimpsests, we are kluges as well.”

- The reviewer concludes: “Unsurprisingly, I’m imperfect, you’re imperfect, everyone and everything is imperfect. Mr. Pievani is imperfect—his writing doesn’t sparkle, but his ideas assuredly do, which makes Imperfection a perfect way to begin understanding our imperfect world.”

The fact that life is permeated with imperfection explains a lot: why our politics are such a mess, why the Dodgers (with the best record in baseball) didn’t make it past the first round of the playoffs, why we can’t live anymore with just one password, and why inflation and gas prices are high. It also explains my disappointment when I must forgo Toll House Chocolate-Chip Cookies, Gallo salami, and Costco hot dogs (well, most of the time). And it’s a logical way to look at what keeps doctors, surgeons, pharmacists, dentists, and psychologists in business.

It seems the Great Cosmic Designer clearly did not consult Martha Stewart before allowing the Big Bang to fumble us all into existence.

But I don’t find this a pessimistic perspective. I think it reveals why there is a poignant beauty in life.

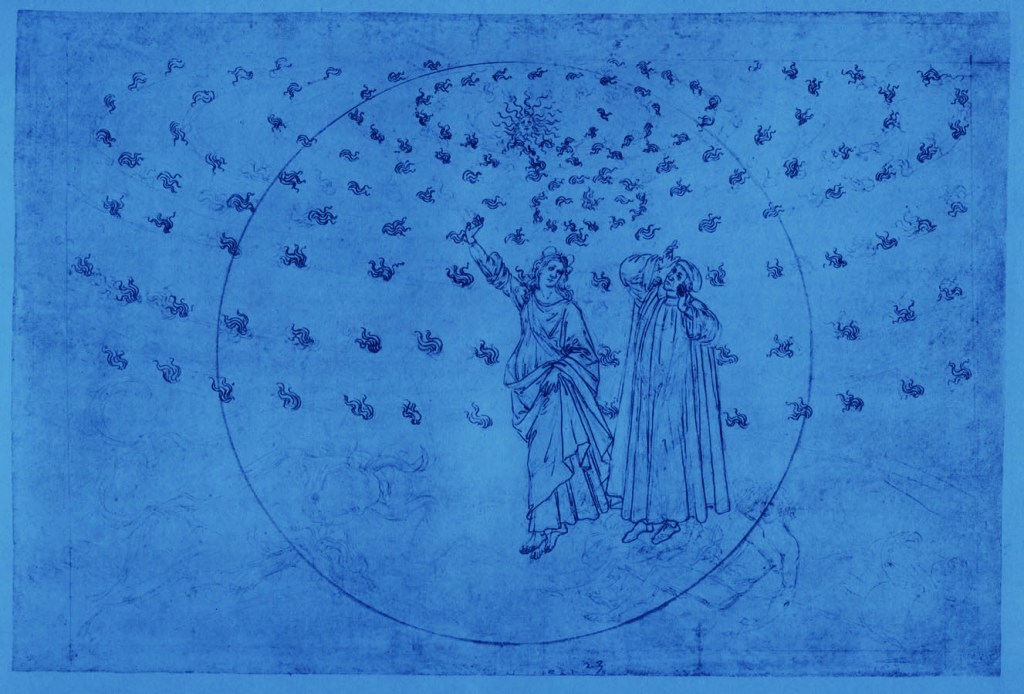

A certain ancient book has two creation stories back-to-back.

The first one is a creation-in-seven-day story. Composed some 2,500 years ago before modern science, it’s an elegant account of light coming out of darkness, land out of the sea, and the emergence of plant life, sea creatures, and humans (created with gender equality). It ends with “And behold, it was very good” and a command to take a day of rest to savor it all. Aren’t there moments when we see the interrelationship of all life and sense it is beyond amazing? It feels like a kind of perfection.

The second story focuses on a man formed from earth who assumes he is the center of everything. He’s given lots of animal companions, but he’s still lonely. A woman is created. They discover a freedom to make choices. They get in trouble and are expelled from Easy Street. She’s cursed with the pains of childbirth, he’s cursed with the frustrations of hard work, and a poor serpent must be forever wary of someone stepping on his head. It’s a human story of promise, longing, hope, confusion, choices, regrets, and struggle — imperfection.

Between the two stories lies all the glories of this improbable life, right alongside the tragedies, heartbreaks, and back aches.

Maybe some people think this imperfect world is a just a cosmic mistake and would prefer to live in Martha Stewart World. But not me.

An art history teacher once pointed out that Dutch still-life paintings often depicted beautiful flowers, fruit, and beverages – but something is amiss. Something is beginning to decay, or there’s an uninvited fly on the peach or in the beer. The message: we long for a perfection that lasts forever, to have everything stay as we want it to be. But life isn’t like that.

At the same time, we can remember that the fruit, the beer, the light, the artist, the viewer — and the fly — all emerged from the same improbable process. And flies are pretty incredible creatures.

We can feel despair from seeing all the “imperfections” of life. And yet there is a transcendent, translucent, transformative sense of presence amid all the improbability. How unexpected that it’s all here after so many mishaps, “palimpsests,” “kluges” and stumbles.

It’s a relief to not expect perfection in ourselves, each other, or life. It’s a gift to look instead for wonder.

[i] https://www.wsj.com/articles/imperfection-review-unintelligent-design-11666735767

Top Image: A Still Life with Grapes, Peach, Cabbage-White and Dragon-Fly, 1665 Willem van Aelst (1627-c.1683).jpg

Bottom image: Still Life by Johann Georg Hinz (c.1660). German painter