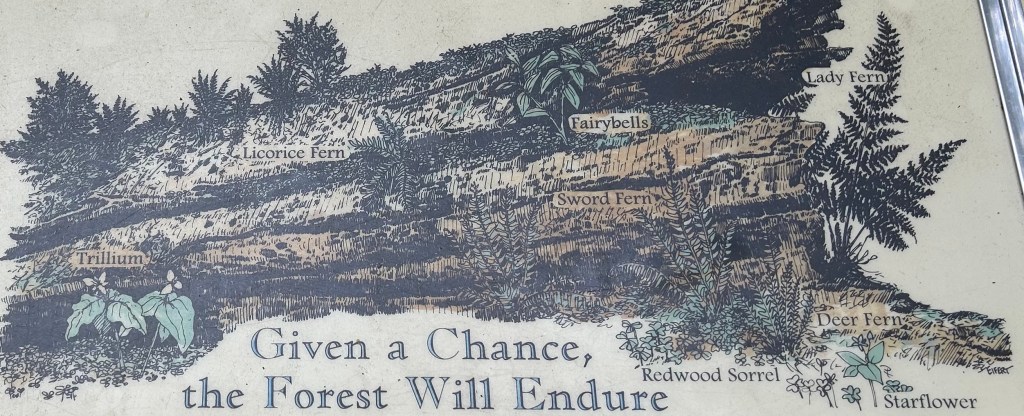

This summer we were driving south on the 101 along the coast of Oregon and Northern California. We were passing through the “Avenue of the Giants” in the Humboldt Redwoods State Park and decided to stop for a break and view the trees. We came across this plaque:

Given a Chance, the Forest Will Endure

A natural coast Redwood forest is preserving itself through a nearly perfect recycling system. Most of the nutrients in the forest consist of living, then decaying plant and animal material.

As this material decomposes it provides nutrients for other living organisms.

Fallen trees account for as much as 40% of all organic material on the forest floor and many plants benefit from growing on these decaying nurse logs. Because redwood is an extremely long-lasting wood, the decay process may take centuries before all of a nurse log’s nutrients have re-entered the forest system.

Today this enduring forest will continue only if we as good land stewards allow it to.

Being uneducated in the way of forests, I never knew that fallen trees are a critical part of the redwood “nursery,” and that some trees may take centuries to patiently pass on the organic material that made their lives possible. The more I thought about it, the more I thought of parallels to our own human life cycle.

When we are young, we are nourished by those who are caring for us in the way of food, shelter, love, and guidance. We are unaware of our dependence on the “nursery” that supports us.

We grow into our teen years. We may find ourselves looking up at the adult trees around us and become determined to find our own way upward. We may think it will be easy to do.

We launch out on our own, finding a path to the sunlight that’s not blocked by the older trees. There’s lots of sap flowing, and we can be fearless in our ambitions and expectations.

Adulthood comes. We find times of satisfaction and accomplishment. We also experience storms or fires; we learn life is not without risk. At some point, we may begin to be as concerned about the younger saplings below us as the unconquered space above us.

Years pass. We realize we are approaching the age and height of our ancestors. We appreciate for the first time the hard work of becoming an elder. We now identify with all those older trees that were invisible to us when we were young. We are now one of them.

Maybe we survive and thrive for a long time. But at some point, we will fall to the forest floor. We’ve lost the lofty, open-sky perspective that we took for granted and now lie close to the ground where our life began. We realize we are part of a life cycle and our role is shifting – now it’s more about releasing our energy to the next generations than holding it just for ourselves. We may wonder: Will the saplings remember what we are doing for them, or will they, like us when we were young, take it all for granted?

A long period of time has passed, but it can seem like an instant. Did we appreciate it while we were living it?

We worry about the future of the forest. Will it survive the challenges to come?

Older redwoods pass on their organic material. Humans don’t have much carbon and nitrogen to offer. We can be nurtured by the lives and stories of our parents, mentors, and ancestors. We in turn try to pass on our awareness, hard-learned lessons, and love to the emerging generations. We want the best for the forest and are grateful to play our part, yet we also realize we are not masters of its fate.

“For everything, there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven…” (Ecclesiastes 3:1)

Photo from Dreamstime.com