A good friend of mine shared words of wisdom he often heard from his father, a cardiologist. When patients would wonder why their heart needed work, he’d simply say, “Miles on the vehicle.” And I’ve heard a similar response at the office of an orthopedist, “Parts wear out.”

We know this is true with cars. With our Honda CRV, we faithfully follow the service schedule, and often it needs nothing more than an oil change and lube. But there are times of “major service” when key parts need to be carefully inspected and possibly replaced. Our mechanic says if we stick to the maintenance schedule, the car can easily reach 200,000 miles and beyond.

The same is true for furnace filters, water filtration systems, and roofs. We want them to last as long as possible but know they will eventually need to be replaced.

What’s true in the realm of mechanics is true of our bodies.

One of the joys of childhood was losing baby teeth. That meant you were getting older. It also meant you could exchange a worn-out part for some hard currency by depositing the tooth under your pillow. (This may be the last time we will show a profit from having parts replaced.)

Life goes on … parts wear out.

For several years, I had pain in my right arm that increased over time. I went through the usual exams and X-rays, and eventually an MRI. I met with a surgeon. He recited a list of what was causing my problem: bone fragments, torn tendons, arthritis, etc. I was surprised at how much wear and tear there was under the surface. But I also thought, “It’s pretty amazing all these moving parts have been functioning without complaint day after day for 70 years.” We scheduled the surgery. He made the repairs. I wore a sling for a month and went through the usual physical therapy. Now I’m pain-free. I can pick up our granddaughter with ease. Parts were wearing out, and I’m grateful for the repairs.

In the meantime, what of our spirit? Does our spirit wear out like our bodies?

One theory is that our inner awareness dies with our body. That may be the case.

Many spiritual traditions assume that the awareness that dwells within us does not die when the body dies. Neither does it wear out. It’s not a part we ever replace.

St. Paul was not only a scholar but also practiced an important trade in the first century: tentmaking. Roman armies required canvas tents, and all the ships that sailed the Mediterranean used canvas sails. Paul earned his income making and repairing them. As he cut and sewed, he must have had plenty of time to think about what wears out and what endures. In one of his letters, he wrote:

16 So we do not lose heart. Even though our outer nature is wasting away, our inner nature is being renewed day by day. 17 For our slight, momentary affliction is producing for us an eternal weight of glory beyond all measure, 18 because we look not at what can be seen but at what cannot be seen, for what can be seen is temporary, but what cannot be seen is eternal. For we know that, if the earthly tent we live in is destroyed, we have a building from God, a house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens… 5 The one who has prepared us for this very thing is God, who has given us the Spirit as a down payment.

I’m not quite sure if there are heavenly houses for us out there somewhere. But I get the point: we live in our “tents,” but are not limited by them. Our true essence is this mysterious presence we call spirit or soul which is not subject to the same wear and tear as our bodies.

Native cultures assume that the spirit outlasts our “parts” and is fundamentally connected to our ancestors. In some schools of Buddhism, the practice of meditation can lead us into the limitless field of “open awareness” that is untouched by death. This field can absorb all our fears and pain and give us a sense of profound peace.

As I think about these teachings, I think of the concept of “agape,” a divine love that underlies all life. Our everyday emotional “loves” may ebb and flow, but “agape” is timeless. We do not create it or possess it; we access it through an open heart and mind and can experience a “peace that passes understanding.”

I bought a Prius in 2008. Five years later I used it as a trade-in for the CRV. When it was time to drop it off, I took all my personal possessions out and drove it to the dealer. We finished the paperwork, and I handed the salesman the keys. I started to walk away, then paused and looked back. I thought of how much life I had lived in that car, and now I was leaving it behind. I was struck by how worn and empty it looked. I wondered, ‘Is this what it’s like when we die?”

Parts wear out. But we are not just our parts or the sum of our parts. We are not our thoughts, fears, or feelings. We are something more. Something subtle. Mysterious. Wondrous. And beautiful.

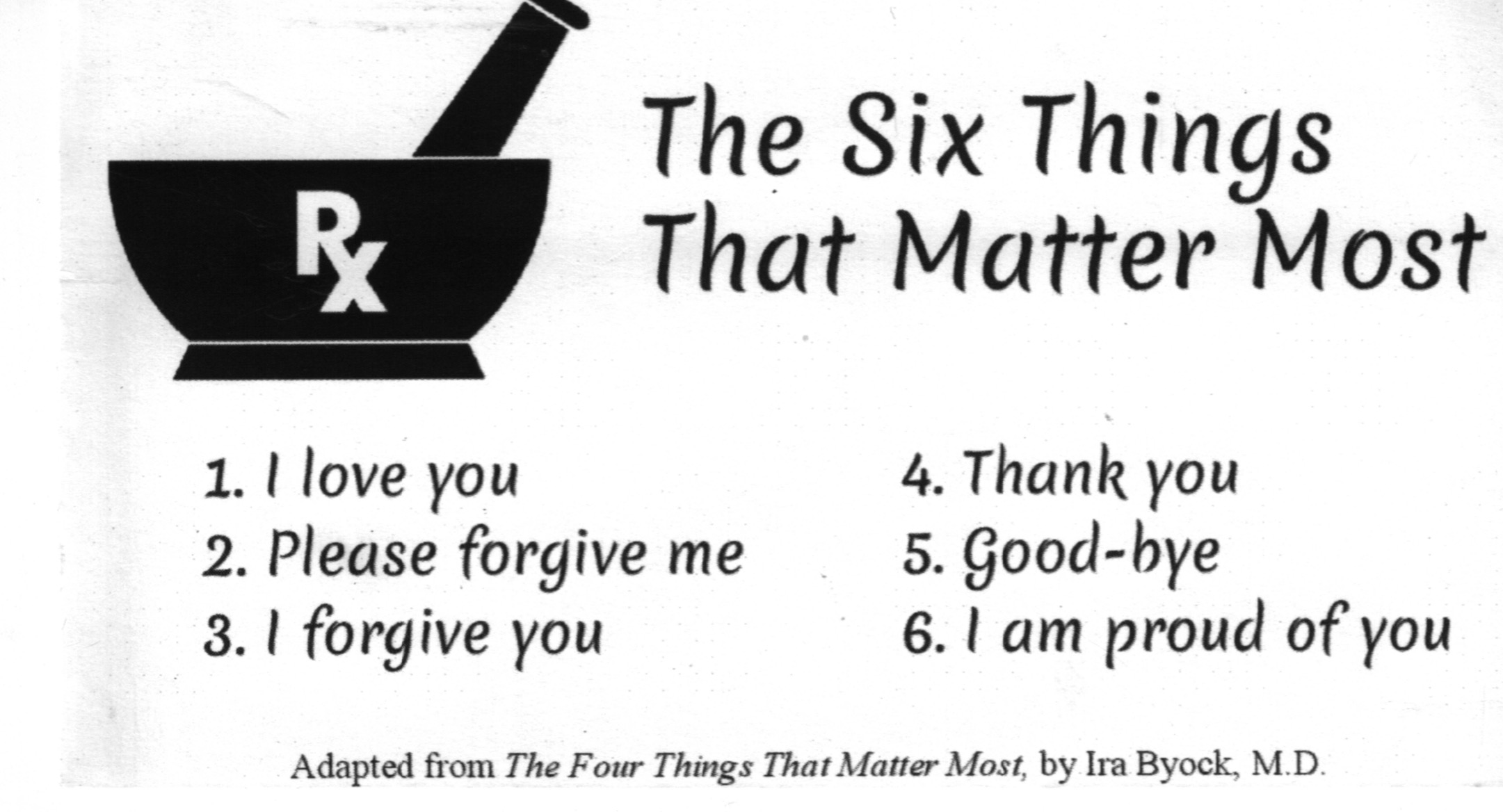

I was grateful to have the card when my father was dying.

He was in his last days at a nursing home. My two sisters and I used the list as a prompt for talking to him. He was no longer responsive, but it felt like the right thing to do. Maybe he heard us or maybe not. Maybe he could sense what we meant through tone or feeling. Or maybe it was just for us.

“Dad, please forgive me for the sleepless nights I gave you as a teenager.”

“There were times when I was growing up when I was afraid of your anger. I knew you were under a lot of pressure and loved us, but it was still scary. I forgive you.”

“Thank you for providing for us, encouraging us and believing in us.”

“For the way you worked so hard to honor mom and provide for us, for the integrity and honesty with which you lived your life, and for your service to our country during the war – we are proud of you.”

Dad wasn’t from a generation when many men would say “I love you.” But we knew he loved us. It was easy for each of us to say, “I love you, Dad.”

The “Goodbye” statement can be tricky. It can be tempting to say it to have some closure, but it may be too early. (I remember one family had asked a harpist to play in the room; the patient woke up and said, “Get that music out of here…I’m not ready for the angels yet!”) But if, say, a family member is leaving town or death is clearly imminent, then “Goodbye” can be fitting.

As I did presentations on hospice in the community, I would pass these cards out. People would later tell me how helpful they were.

But I also knew what everyone who works in hospice knows…the work is not just about the dying, but also about the living. Whether dad was fully aware of what we were saying, it gave us closure.

The list can also be helpful after a death when we didn’t have an opportunity to speak the words in person. We can write a letter to the person using the list as possible prompts. We can then save the letter just for ourselves. Or we can take it to a place we associate with the person, including a gravesite, and read it. When it’s served its purpose, we can keep it or create a simple ritual and burn it.

“Six Things” can also be valuable when death is not on the horizon. Roughly half of Americans die with some form of hospice care, which means there may be time for meaningful bedside moments. It also means the other half of us will die without such an opportunity – heart attacks, strokes, accidents, etc. If these are the six things that matter most, why wait for a moment that we may never have? Why not use them when we are alive and well?

As time went on, I’ve found the “Six Things” a good way to take inventory from time to time in my own life on occasions like anniversaries and birthdays. Is there someone I want to say these words to now since there’s no guarantee I’ll have a chance in the future? Or maybe take one each day, and say it to someone during the day if the time feels right? It doesn’t have to be a dramatic act, just a sincere one. What do we have to lose? Once we do it, we often experience a sense of freedom.

I was grateful to have the card when my father was dying.

He was in his last days at a nursing home. My two sisters and I used the list as a prompt for talking to him. He was no longer responsive, but it felt like the right thing to do. Maybe he heard us or maybe not. Maybe he could sense what we meant through tone or feeling. Or maybe it was just for us.

“Dad, please forgive me for the sleepless nights I gave you as a teenager.”

“There were times when I was growing up when I was afraid of your anger. I knew you were under a lot of pressure and loved us, but it was still scary. I forgive you.”

“Thank you for providing for us, encouraging us and believing in us.”

“For the way you worked so hard to honor mom and provide for us, for the integrity and honesty with which you lived your life, and for your service to our country during the war – we are proud of you.”

Dad wasn’t from a generation when many men would say “I love you.” But we knew he loved us. It was easy for each of us to say, “I love you, Dad.”

The “Goodbye” statement can be tricky. It can be tempting to say it to have some closure, but it may be too early. (I remember one family had asked a harpist to play in the room; the patient woke up and said, “Get that music out of here…I’m not ready for the angels yet!”) But if, say, a family member is leaving town or death is clearly imminent, then “Goodbye” can be fitting.

As I did presentations on hospice in the community, I would pass these cards out. People would later tell me how helpful they were.

But I also knew what everyone who works in hospice knows…the work is not just about the dying, but also about the living. Whether dad was fully aware of what we were saying, it gave us closure.

The list can also be helpful after a death when we didn’t have an opportunity to speak the words in person. We can write a letter to the person using the list as possible prompts. We can then save the letter just for ourselves. Or we can take it to a place we associate with the person, including a gravesite, and read it. When it’s served its purpose, we can keep it or create a simple ritual and burn it.

“Six Things” can also be valuable when death is not on the horizon. Roughly half of Americans die with some form of hospice care, which means there may be time for meaningful bedside moments. It also means the other half of us will die without such an opportunity – heart attacks, strokes, accidents, etc. If these are the six things that matter most, why wait for a moment that we may never have? Why not use them when we are alive and well?

As time went on, I’ve found the “Six Things” a good way to take inventory from time to time in my own life on occasions like anniversaries and birthdays. Is there someone I want to say these words to now since there’s no guarantee I’ll have a chance in the future? Or maybe take one each day, and say it to someone during the day if the time feels right? It doesn’t have to be a dramatic act, just a sincere one. What do we have to lose? Once we do it, we often experience a sense of freedom.