This is a season of ghosts and spirits. Let’s imagine your “ghost” is out and about for a few hours. You find yourself walking in a neighborhood you’ve never been in before. You notice there are three houses side by side. As you approach the first one, the door opens. You enter.

- House #1: You find yourself descending into an underground complex, and the door shuts behind you. You walk through an ancient gate, are ferried across a river, and are assigned a place on one of the nine floors. You realize this is a place where you will never have to pretend to care about anyone else. Instead, you have unlimited time to proclaim to anyone within earshot how other people and forces were responsible for all the disappointments in your life. There are other “ghosts” on the floor with you, but no one seems to even know you are there. But you don’t care. You start ranting about divine injustice, the influence of the stars, your terrible family, and all the people you encountered who did you wrong. Occasionally one of the other ghosts floats your way and pours out their own misery and outrage, but you don’t even pretend to listen to them – you just continue your diatribe.

- House #2: In the blink of an eye, you find you have left the first house and are in front of the door of the second. You enter and join a group of fellow spirits. You are all standing at the base of a mountain. Everyone seems glad to have arrived, and they sing a song of gratitude. The group begins a long hike up a mountain. You can’t travel alone – you must stay with your group and support each other. From time to time, someone will start singing a familiar song and everyone joins in. You have a guide who seems very knowledgeable and ready to answer any questions you might have. You find yourself taking time to make a personal review of your life. As each important experience comes up, you take responsibility for your actions and learn something new. As you do this, you feel burdens of regret that you’ve been carrying for a very long time being lifted. You get to the summit and enter an enchanted garden; personal guides come to welcome you. In an instant, you find yourself back on the street in front of the third house.

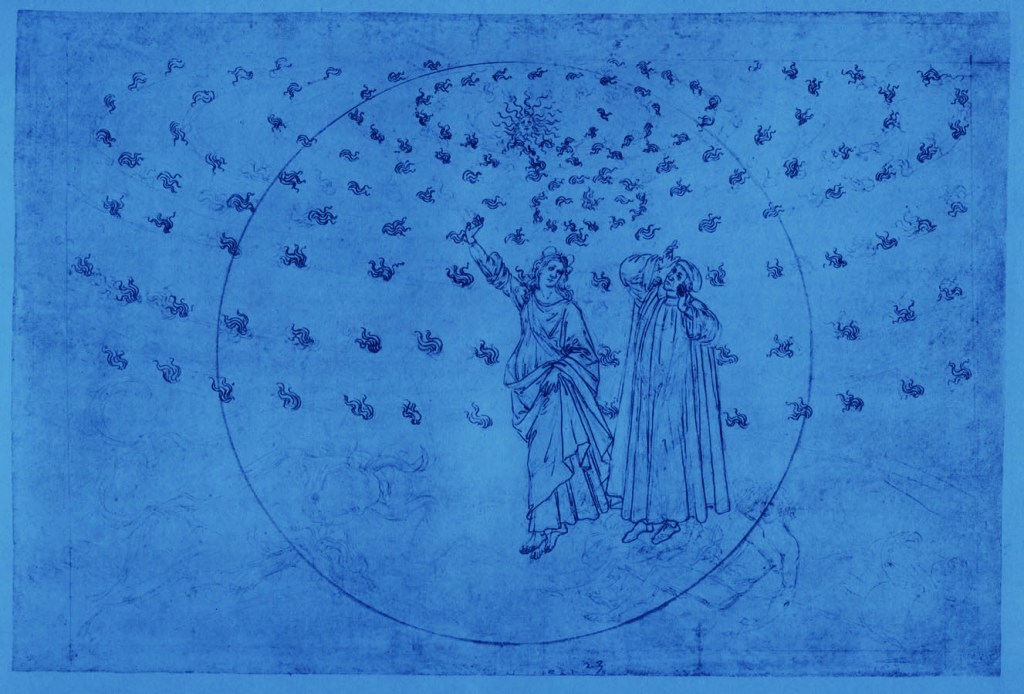

- House #3: As you walk through this door, you feel weightless and buoyant, and realize you are ascending through the atmosphere toward the heavens. You find yourself on the moon. You feel refreshed and renewed. You realize you can remember details of your life, but you’re no longer preoccupied with yourself. Instead, you are fascinated by the other people you are meeting along the way – some you know from your life, and some are new acquaintances. You can’t help but marvel at their essential goodness. You’re also enraptured by seeing the moon, planets, and stars with amazing clarity. You notice that some people are positioned above you, closer to the source of light. But you don’t care because you are no longer comparing yourself with others, and you know that to be anywhere in this dimension is to be filled with wonder, appreciation, and freedom. Then, suddenly, you’re back on the street.

These are, very roughly speaking, characteristics of the three dimensions of the afterlife described by Dante in 1300 in his masterwork, The Divine Comedy. It reflects his personal understanding of the universe, human behavior, and spiritual truth. It arises out of his own beliefs and biases and is a product of its time. But, like all great imaginative works of literature, it contains great insights into human behavior. House #1 is a sample of what it’s like to be in Inferno, where you are endlessly immersed in your own self and your prejudices and don’t give a damn about anyone else. Destination #2 is “Purgatorio,” where you have the chance to work through whatever has burdened you, aided by being in community with others. And Destination #3 is an imaginative glimpse of Paradiso.

I don’t know exactly what happens when we die.

What I do know is that Dante captures what we can experience in the here and now.

To be constantly engulfed and isolated in anger and resentment is like existing in a living hell.

To be on a spiritual journey is like being on a long trek where we learn more and more about ourselves and life every day and, as we make the journey, we learn the importance of friendship and caring for one another.

And having moments when we forget ourselves and, instead, catch glimpses of the beauty of the natural world and other people is like finding heaven on earth.

Image above: “Piccarda Donati meets Dante and Beatrice on the Circle of the Moon,” Canto 3 Paradisio; Salvador Dali

Image below: “Beatrice Shows Dante the Fixed Stars,” Boticelli