We live life within the stories we create about ourselves. But, unlike testimony we give in a court of law, we can change our stories if we choose.

In a writing workshop, Marilyn McEntyre encouraged us to revise our life stories as often as needed. She points out that the original meaning of “re-vise” is to “look at again, visit again, look back on.” [i] She encourages anyone (including the people with serious illnesses whom she works with), to not get stuck in our old narratives. You are the author of your life, she says. Events beyond your control may impact you, but you’re free to decide how you will respond, what role you will play, and who you become.

Thinking about this reminds me of similar insights I’ve heard over the years.

In a blog post two years ago, I shared a comment attributed to Jonas Salk, the creator of the polio vaccine. When asked what had enabled him to become a successful experimental scientist, he credited his parents. If he would spill milk in the kitchen, Salk said, they would not get angry with him. Instead, they’d ask, “What did you learn from that?” This perspective guided Salk in his scientific career, encouraging him to not be afraid to try things. If we make a mistake, we can re-visit the experience, see what we can learn from it, and decide what to do differently next time.

I have also shared a comment Parker Palmer made about the term “disillusionment.” When we say we have become disillusioned, we often say it with a sense of sorrow or defeat. But, he said, think of what the word means: to be dis-illusioned means we realize we had an illusion and it’s been “dissed.” Instead of feeling discouraged, imagine we’ve been liberated from mistaken assumptions, open to a clearer sense of the truth.

Looking back on my life, there have been times when I have trusted some people too soon and too much. When I eventually recognized it, I felt frustration for having been naïve. But I can “re-visit” the experience and accept I was the one who created the “illusion” of what to expect. I can be grateful my illusion has been dissed, and plan to be more careful next time. (I’m still working on this.)

I remember a hospice study in which a medical team examined why some people die in misery and others — with the same illness — die with a sense of peace. One of the factors they identified was “Experience of a sympathetic, nonadversarial connection to the disease process.”[ii] I can see cancer as a dark, malignant force that is attacking me as a personal aggressive act; if it “wins,” I have not only lost my health but been humiliated and defeated. But I can see it from a different perspective: cancer is a common occurrence with living beings and there’s nothing personal about it. I will still do all I can to send it into remission, but cancer doesn’t define who I am as a person, nor will it ever be able to harm my spiritual essence which will survive death. It’s not easy to navigate this process, but I have seen people “re-vise” their understanding of life and illness and find a sense of peace. A new perspective is powerful medicine.

A common teaching in the spiritual traditions is to be honest about our short-comings and mistakes, but not be bound by them. Instead, we accept the grace, compassion and forgiveness that comes from a source beyond our egos while remaining thoughtful about our own behavior. Re-vising our life stories does not mean we are avoiding or denying the facts of what happened; instead, we are finding a fresh perspective that can empower rather than diminish us.

[i] https://www.etymonline.com/word/revise

[ii] “Healing Connections: On Moving from Suffering to a Sense of Well-Being,” Balfour Mount, MD,Patricia Boston, PhD, and S. Robin Cohen, PhD; Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, April 2007 (Other factors named in the study: “Sense of connection to Self, others, phenomenal world, ultimate meaning; Sense of meaning in context of suffering; Capacity to find peace in present moment; Ability to choose attitude to adversity; open to potential in the moment greater than need for control)

Marilyn’s publications and workshops, including her work with people dealing with illnesses, can be found at MarilynMcEntyre.

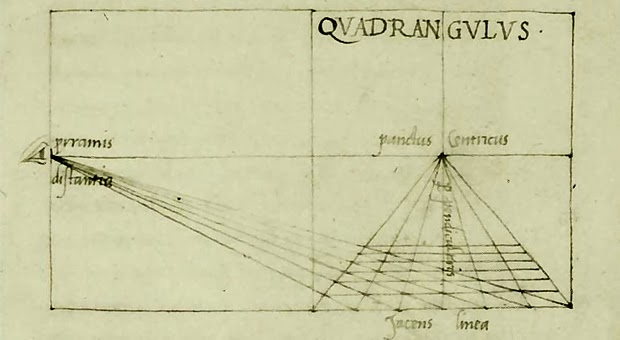

Lead Image: “A Lady Writing,” Vermeer, 1665, National Gallery of Art; lower image: “Quadrangulus,” Milra Artist Tools, LLC