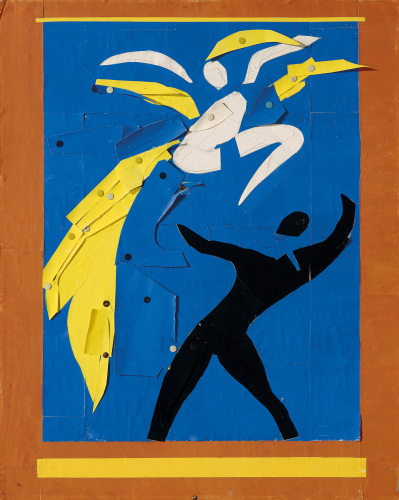

Imagine visiting a gallery and coming upon this painting for the first time without knowing its title. What do you see?

I see the farmer with the red shirt guiding the blade of his plow.

I see the ship sailing in the nearby channel. Having just taken some sailing classes, I’m curious about the design of the ship. The sails on the bow and stern are capturing a strong wind; those on the central mast are not extended. If they were unfurled, would the wind blow too strongly and make navigation difficult?

I notice the shepherd looking at the sky with his dog by his side and the sheep grazing. Is he looking at a specific object, or just daydreaming?

My attention moves to the background where I see the harbor and a few buildings.

I’ve seen enough. A visual “slice of life” from the mid-16th century. Interesting. Sort of.

But then I happen to see the brass plate next to the frame: “Landscape With the Fall of Icarus.”

What? Where’s Icarus?

Taking a second look, I discover Icarus in the lower right-hand corner –a pair of legs entering the sea with feathers fluttering in his wake.

How did I miss him?

In the Greek myth, Daedalus learned how to make wings using feathers and beeswax. His son Icarus is young and wants to fly. His father warns him he must not go too close to the sun, or the wings will melt, and he’ll fall to earth. But Icarus is young and confident. He ascends. The wings melt. He falls to his death in the sea.

Looking at the rest of the scene a second time, I realize no character seems to notice him. Reading about the painting, I discover that’s the point.

People are in trouble around us every day. A young man’s life ends and what are we doing? Farming? Sailing? Staring at the sky? Fishing?

The story of Icarus evokes something personal for me.

In my early 20s, I’d had what Jung called an inflated ego. I had become isolated and was taking risks with my life. Like Icarus, I believed I was immune from any serious consequences. But then I had a personal crisis which put me in peril. I could have easily fallen into the sea, unnoticed by people around me until it was too late. If not for the grace of God, I don’t know how I would have survived.

Hidden tragedies and pain are no doubt being carried by people we pass every day –at Trader Joe’s, at Costco, at work, or walking in our neighborhood. Do we notice them?

I was at the local movie theater recently to see “West Side Story.” After the film ended, the small crowd was exiting while the theater was still dark. Just in front of me, an elderly gentleman with a cane fell to the floor. His wife had charged ahead and didn’t see it. I knelt and asked if he was alright, and carefully helped him stand up. He regained his balance but seemed dazed. His wife came back and, a bit impatiently, told him to follow her.

Don’t most of us want to notice others in need and help when we can?

But can we spend our entire day on the lookout for strangers in trouble?

Looking again at the painting, I notice new details.

Take the farmer. He’s not working a flat prairie field in Kansas where he could let his attention go elsewhere. He’s plowing a steep hill which requires extra focus. He needs to do this well if he’s to care for his land and raise food for his family and village.

How about the sailing ship? The ship is passing through a narrow channel. The captain and crew need to be on alert for any changes in the strong wind, ready to respond in a skillful and timely manner if they are not going to run aground or collide with another ship. They must bring their full attention to their work to be safe while make a living.

And the shepherd. If that was my job and all seemed well in the moment, I might get lost in thought – I don’t think I’d be constantly scanning the horizon looking for someone in danger.

This time I notice the fisherman in the red hat. He is the closest. I don’t know why he doesn’t notice Icarus splashing in into the sea.

A part of me identifies with those other characters, not just Icarus. When we have responsibilities, we need to attend to them.

I say that to myself, but something tells me that may be a way to let myself off the hook from being alert to the suffering of others.

The great spiritual traditions implore us to care for the stranger, to be our “brother’s keeper,” to be Good Samaritans in a world of self-absorption. I believe most of us do so when we can. But can we do that all the time?

This isn’t a pleasant pastoral scene. This is a soul-scan revealing the tension between our personal responsibilities and the call to care for others.

Life is complicated.

What a great work of art.

Landscape With the Fall of Icarus, Brueghel, c 1560

Dear Reader: On March 6, there was a stunning interactive piece in the New York Times exploring this painting and how it inspired a famous poem by W H Auden: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/03/06/books/auden-musee-des-beaux-arts.html.

I had been meaning to write this modest reflection of my own before reading that article, and, after reading it, almost shelved my piece as it seems a bit simplistic. But I believe all great art invites many interpretations, even the humble ones.