For more than a decade, I’ve been entranced by the great three-part medieval poem, Dante’s Divine Comedy. There are many spiritual and psychological insights Dante shares in this work that speak to me. In this posting, I want to share his concept of two symbolic rivers we might sample in our life journey. The description occurs near the end of the second volume, Purgatorio.

By this point Dante’s been given a tour of hell (Inferno) and all its custom-made torments. It’s impressive to see how he imagines the bad guys “get what’s coming to them,” as they used to say in the Westerns. But Inferno is not as meaningful to me as what follows.

In Purgatorio, he imagines hiking up a mountain to see how all kinds of people are completing their personal soul-work as they prepare for Paradiso. (Does he – or anyone these days — really believe in a place like purgatory, you might ask? Don’t worry about it, dear reader; let’s just follow what he imagined.)

As he gets to the top of the mountain, he travels through an enchanted forest and, among other experiences, comes to two rivers. He also encounters a guide, Mathilda. The first river Mathilda leads him to is the Lethe, which was known in Greek mythology as the river of forgetfulness we pass through after we die. Dante interprets it in a positive way:

“She plunged me, up to my throat, in the river

And, drawing me behind her, she now crossed

Light as a gondola, near the blessed shore, I heard

“Asperges me,” so sweetly sung that I

Cannot remember or, much less, describe it.” (Canto 31: 94-99)

“Asperges me” means “thou shalt sprinkle me.” After guiding him across the river, she invites him to take a drink. All the memories of the mistakes he’s made in life – the poor decisions, the times when he’s hurt someone else or disappointed himself – all are washed away in the Lethe. Think about your regrets in life – what would it feel like to have the painful memory of them disappear?

After more encounters and reflections, he comes to the second river – one Dante created out of his own imagination — the Eunoe. Matilda is joined by a group of guides and invites Dante and a fellow pilgrim to drink from it. After he does, he says:

If, reader, I had ample space in which

To write, I’d sing – though incompletely – that

Sweet draft for which my thirst was limitless…(Canto 33: 136-138)

Where the effect of drinking from the Lethe was to allow him to forget all his failings, drinking from the Eunoe allows him to recall all the good deeds he’s done in life, both large and small. (The word he created, eunoe, combines eu(new) – and noe(mind) – a new, fresh mind.)

Think about it. Sure, you’ve made mistakes in life. But you’ve also done many good things – small kindnesses, acts of love and duty, promises kept, hope given, and friendships honored. Imagine what it would be like towards the end of life to forget all the bad stuff you’ve done and remember all the good?

From the first time I read about these two mythic rivers, I was entranced by imagining what such an experience would feel like. In the years since, I’ve come to wonder if sometimes people actually experience something similar.

My father outlived my mother by 19 years. We knew they loved each other all the years they were married. But we also remember their life together was not free from the stresses and strains of many long-term relationships. Yet in his last years, whenever dad reflected on their time together, all he talked about were the joys they’d shared — no mention of the hardships. At first, I was tempted to kindly point out it wasn’t all milk and honey. But something told me to be quiet. It was as if dad had dipped first into the Lethe, then the Eunoe, and the combination filled him with pure gratitude.

Recently I visited a former parishioner who had decided to stop receiving life-prolonging treatments. She’d been through many challenges in her life, including years of concern for her children and the obstacles they faced. But, she told me, they were both doing well now and didn’t need her as they had before. She was tired of the complications her body was having to endure every day and she wanted to be free. When I came, she was going through a box of old family photos. After I sat down, she showed me some of her favorites. Each memory had become a delight. Before I left, I asked her if there was anything she’d like me to pray for. She told me, “Somebody said, If the only prayer we ever offer is thank you, that would be enough. Just say how grateful I am.’

Remembering our mistakes helps us to stay humble and keep learning how to do better. Focusing only on the good we’ve done may seem selfish. But maybe, once in a while, we can close our eyes and imagine sampling those waters – tasting what it’s like to have our regrets washed away, then savoring a pint of gratitude for the good things we’ve done. Maybe we shouldn’t wait until late in life to see what these magic waters can teach us.

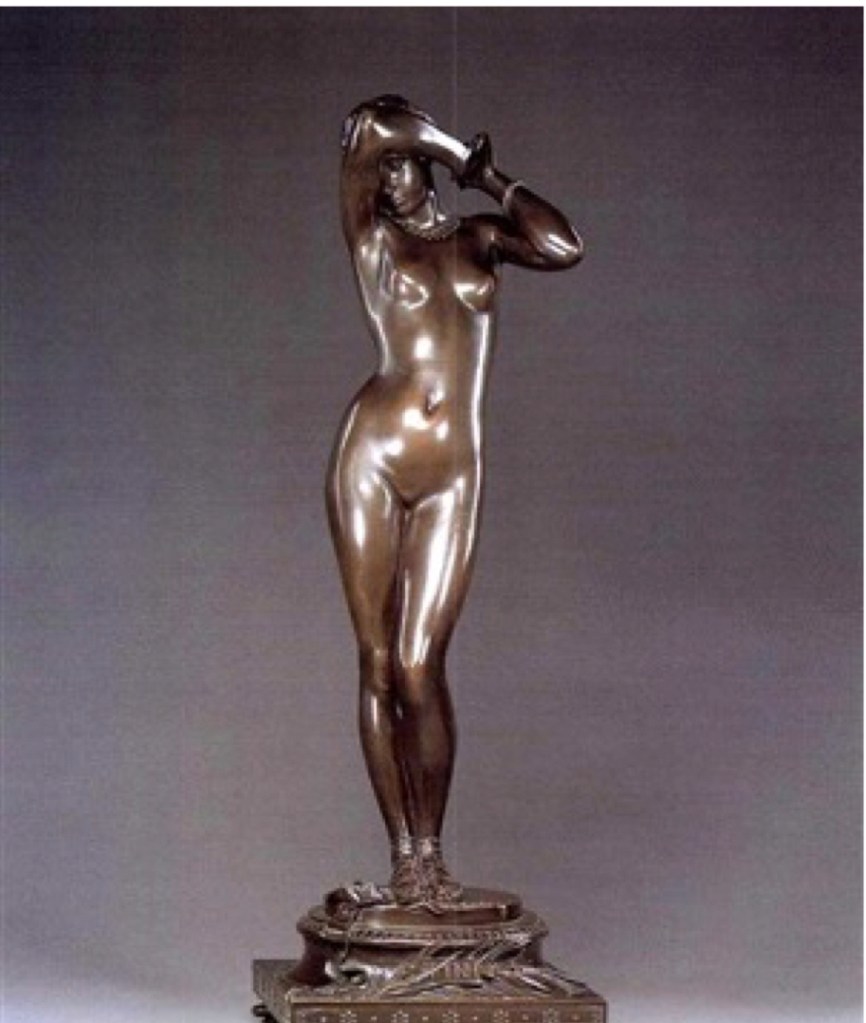

Painting: “Along the River Lethe,” Kyle Thomas