Imagine you’re about to do something important and you want to be at your best. Maybe you are going to visit a friend who is facing a personal challenge. Or maybe you are about to begin a creative activity you enjoy. Maybe it’s an action that requires skill and concentration. In each of these situations, what can you do to prepare yourself?

I recently was introduced to a simple practice that may help in these situations. It uses the acronym G R A C E: Ground yourself, Relax, become Aware, focus on your Center, and Energize.

I’m going to offer my own perspective on what each step means, drawing from the various classes, retreats, trainings, and readings I’ve done over the years. I don’t consider myself an expert, just an explorer. Here it goes:

Ground Yourself — I remember a meditation teacher beginning a session by saying our body is always in the present moment, but our mind is a “time machine” — it’s constantly moving backward into our past and forward into the future, chasing thoughts and feelings. It’s helpful if we can slow it down and anchor it in the “here and now.” We can pause and take three deep, slow breaths, noticing our inhales and exhales, inviting that busy mind to settle into the present. We can pay attention to the sensation of our feet on whatever we are standing on – literally an act of “grounding.”

Relax – Once we are grounded, we take a moment to put ourselves at ease. We notice if there’s a part of our body that is tense and release it.

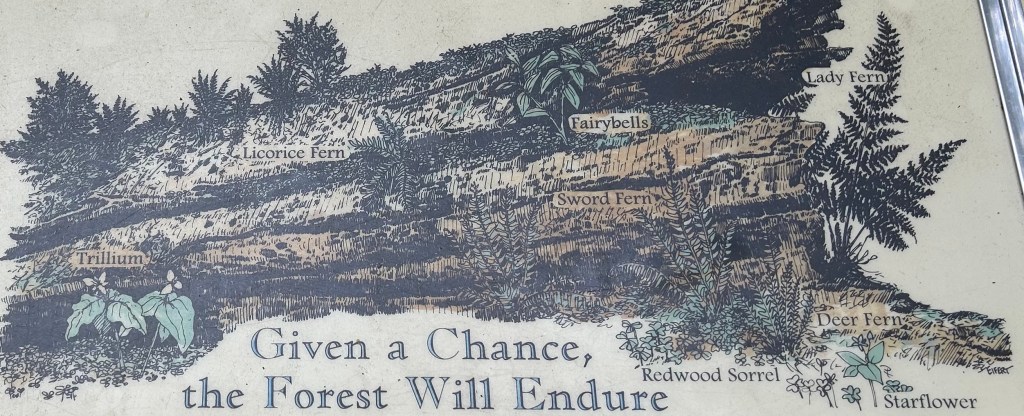

Aware — Grounding ourselves and relaxing, we now invite our senses to tell us more about where we are in this moment. What sounds are we hearing? Any sounds from nature, like a distant bird song? What is our skin telling us – is the air warm or cool? Is there a breeze blowing? If so, do we want to turn and face that breeze the way cats and dogs do when they sit in a doorway, maybe closing our eyes to heighten that awareness? Are there fragrances in the air? What do we see if we look around at our surroundings? Are there subtle and small details in our environment we did not notice at first? We are patient with this process – even if we are taking just a few moments, we are not in a hurry.

Center — When we’ve spent time to ground ourselves, relax, and become aware, our mind may have become more “present in the present.” In that moment, we may imagine that our awareness is no longer being swept along in mental busyness and anxiety, but closer to the “center” of who we are.

Energize is the final step. This is when we calmly move from this time of focusing to engage in whatever activity is before us – knocking on the door of the person we are going to visit, beginning a physical or creative activity, or just consciously entering our day.

I’ve been exposed to these techniques at different times in my life, but I think GRACE is an easy way to remember these practices in a sequence.

Here’s the Big Reveal: I came across this practice not at a monastery or mindfulness retreat but at a recent golf event. The event was organized by an international group that uses golf as a spiritual practice. Doing this routine before making a shot has surprising results – the shot often goes better than expected. If it doesn’t, we don’t get upset because we’ve become aware of the wonder of being alive in the moment. This practice quite simply makes the game much more interesting and enjoyable, whatever the outcome.

I once attended a hospice training retreat in Marin County led by a teacher who was a long-time friend of the popular spiritual writer Ram Dass. At one session we were able to Skype with him from his home in Maui. Ram Dass was relaxed and shared some general comments about “presence” and was fielding questions. Suddenly his expression changed. He became very serious and, addressing our group, said, “You are not a collection of your thoughts. You are loving awareness.” I’ve heard many definitions of “soul” and “spirit” over the years, and I found this one intriguing. Maybe at the deepest part within us, we are “loving awareness.” If so, that is our center.

By going through this process, we re-mind ourselves that we are more than just a busy brain loosely attached to a body. We are embodied human beings who have been gifted with this amazing multisensory life-form and a miraculous mind which, when they are working together, can open us to a rich awareness of where we are and what is possible.

GRACE brings together a variety of popular contemplative practices in a simple, memorable way. No matter what situation we are facing, who doesn’t want to experience it with a tangible sense of grace?

Photo: UCSB Lagoon