If there’s one phrase I’ve come to rely on over the years, it’s “You never know.” Like a Swiss Army knife, it’s handy in many situations.

Rachel Naomi Reimen is Professor of Family and Community Medicine at UCSF and creator of a widely used medical school course, “The Healer’s Art.” I’ve appreciated her books, seen her speak several times, and had a chance to meet her personally. Her grandfather was an Orthodox rabbi and master storyteller. In her medical practice, she learned the importance of listening to patients’ stories and being open to mystery, spirituality and the unknown, while still employing the best medical care. A patient would come to her and report that an oncologist had given them six months to live. She sensed the patient assumed the doctor was all-knowing. She knew better. She would offer a different, more open perspective. “Let’s put it another way. This diagnosis means you’ve started a new chapter in your life. But no one knows yet how the story will unfold.” This didn’t change the medical facts, but it more accurately describes what happens in life: you never know where things will lead.

I remember a parishioner named Doug. When I first came to serve the Goleta congregation, I was told he was facing terminal cancer and I should visit him soon. I remember meeting Doug and his wife Marge in their mobile home park and thinking, “What a nice older couple.” As they were telling me about their background, they mentioned that when Doug retired, they did something they always wanted to do. I thought, “They probably went on an Alaskan cruise.” But when I asked, they said they’d gone to Europe, bought a Volkswagen bus and traveled there for two years living each day as it came. I had totally misjudged them.

You never know who a person is or what they’ve experienced until you listen to their stories.

I asked Doug about his cancer. He told me he’d been through a series of chemo treatments and found them quite debilitating. Doctors said he would need another round, or his time would be very short. But he had decided it wasn’t worth it. He decided to stop treatment so he could spend his remaining time enjoying life as best he could, even if it was just a matter of weeks.

Doug did not do any more treatments. He lived two more years. You never know.

And then there are the people that are heathy and fit and doing all the right things. They have a heart attack and then they’re gone. You never know.

This certainly applies to politics. In the 2008 Iowa caucuses, Joe Biden finished fifth with 4% of the vote. In 2020 he was fourth. Now he is president. You never know.

I’m a Dodger fan. The most important game of the year was game 5 in the do-or-die playoff series against the Giants. With the score tied in the 9th inning and a runner at third base, the batter who came to the plate, Cody Bellinger, had the worst batting average on the team. My fan-heart sank. But he poked a single into right field and the Dodgers won. You never know.

By the 1850s, the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard had become well known in his native Denmark. People approached him asking to write his biography. He refused to cooperate. He believed biographies don’t tell the true story of someone’s life. Everyone knows how the story ends, so everything that happens will be seen in that light. But when we are living day by day, we have no idea how our life will turn out. “Life can only be understood backward, but it has to be lived forward.”[i]

Think of decisions you regret. Weren’t you making your best judgement at the time?

Or think of blessings in your life you did not anticipate. Who could have predicted they’d appear?

If we draw on a particular spiritual tradition, it certainly helps to reflect on core principles and spend time in prayer and contemplation. But even then, at some point, we must set a course and hope we made a good choice.[ii]

In real life, we often must make decisions using the available facts and truest feelings we have at the time. How will it turn out? You never know. We just do our best and see what happens.

[i] There is, of course, a long tradition in Western philosophy focusing on the question of what we can really know. I took three quarters of philosophy in college, working from Plato to Aristotle to Descartes to Hume to Kant and into the modern age. In the end, I think you never know. Life is too complicated.

[ii] In Buddhism, a core emphasis is becoming aware of how susceptible we are to becoming attached to ideas and expectations about life that are more illusory than certain. Jesus promises the Spirit can be always present with us, and Paul believes that nothing can separate us from the love of God. These are wonderful reminders, which I live by. But it still leaves us with the inescapable burden of making decisions about our life with limited knowledge.

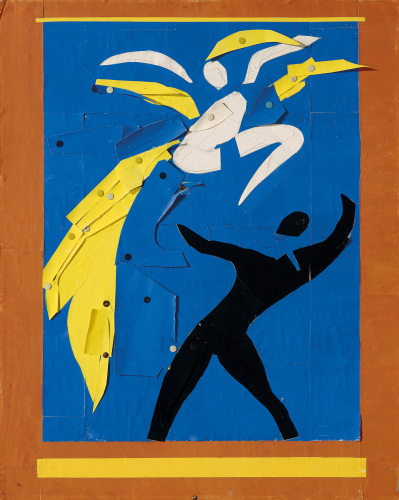

Art Work: “Two Dancers,” Matisse, 1937