Years ago, the great sage and scholar of all things spiritual, Huston Smith, spoke at the Lobero Theater in Santa Barbara. He announced he had five talking points that evening – statements that the Santa Barbara audience might disagree with. But, with a smile, he encouraged everyone to consider them.

Each of the five points was provocative and memorable, and today I will comment on the fifth: “In the end, absolute perfection reigns.”

He said he knew many people would think this is naive. With so much suffering in the world, how can anyone believe perfection will emerge in the end? But he stated it’s one principle all the major wisdom traditions agree on. He also offered a metaphor to appreciate the concept: tapestries.

When you look at a tapestry from behind, it seems like a chaotic scramble of dangling bits of yarn and crossed threads. But if you walk around and see it from the front, you realize it’s actually an integrated, inspiring work of art.

As we live our lives, he said, we can feel like we are creating something that looks like the back of that tapestry. We may go through days and seasons where we feel things aren’t working out the way we hoped, and our life has become a mess. But in time – perhaps, as we keep going, or after we have left this life – the strands we felt were mistakes can be rewoven and incorporated into a larger fabric, and they will form something grand.

I think about my family history. I try to appreciate all that my ancestors went through, and that includes some dangling threads of tragedy, disappointment, and hardship. I want to live my life in a way that honors their accomplishments and also has compassion for what they may have felt were their failings. It’s like I’m picking up pieces of thread from their lives and trying to give it new meaning as I find ways to weave their experiences into my own.

I think about all the suffering people have endured due to race, gender and injustice. I can’t do anything about the past. But I can try to honor those sufferings and work towards a more just and humane world.

I don’t know when my time on earth will be up. I go day by day, weaving my strands as best I can, assuming I’ll die with some left undone. I hope those who follow me can pick those strands up and incorporate them into the lives they live, creating something good out of what I’ve done and from what I left unresolved.

And if all humanity is doing that – if we are learning from the past while doing the best we can –that big tapestry is constantly evolving, and all the strands will ultimately find a place in the bigger work of art.

And if there is a divine force in this world, present in all of nature and within each one of us, and if it’s endlessly at work helping us endure and learn and heal and create and serve – then we are not alone. As we seek divine guidance and direction, we’ll find there’s a master artist at work alongside us, encouraging our creativity and leading us into new and novel patterns of meaning.

As I say this, a skeptical voice within me speaks up. It tells me this is all wishful thinking. “We live, we die, life goes on and that’s it.” I reply, “If that is the way it is, that’s OK…I’m grateful to have lived as long as I have, and to see all I’ve seen, and to have done the best I can.”

But another voice in me thinks Huston Smith — and so many mystics — may be right. In the end, it’s not just about me, it’s about all of us, and that big, evolving, living tapestry we are all part of. Maybe, just maybe, led, inspired, and sustained by divine grace, it will be true: “Absolute perfection reigns.”

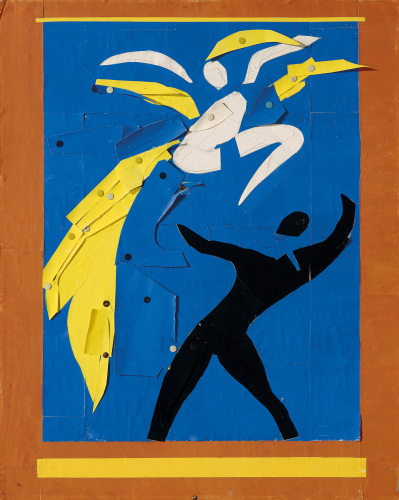

Top Image: Jacquard paisley shawl (detail of front and reverse sides), Scotland, 19th century. Laura Foster Nicholson at https://lfntextiles.comtps://lfntextiles.com https://lfntextiles.com