I’m skeptical about self-help books. They always sound like they are going to lead us to endless happiness if we just set the right goals and remember a few principles, but over time life turns out to be more complicated.

I remember reading a bestseller in 1989: Do What You Love, The Money Will Follow. I tried following the advice. It didn’t work. I think many poets, musicians, athletes, spiritual seekers, and artists eventually realize they need to find a real job to pay the bills while making time to do the creative and imaginative things that bring joy and satisfaction. I’m a skeptic when it comes to simplistic formulas for negotiating life.

However, I have found two suggestions that seem to be worth sharing.

The first comes from my hospice experience: “The opposite of fear is curiosity.” When faced with unwelcome news or unwanted challenges, we may naturally respond with fear. We may choose to be defiant or in denial about whatever is happening. When we are fearful, our ability to think creatively shrinks. (I have a friend and professional leadership coach who tells his clients and his teenagers, “Remember, when you get angry or emotional, your IQ shrinks.”) It’s interesting to consider choosing curiosity instead. Becoming curious feels different. We become calm. Our mind is open. Our mental state and awareness expand rather than contract.

I remember Hank, a parishioner and mentor. He had a Ph.D. in chemistry and spent his career in higher ed and international education. He was also a strong Mennonite, a tradition that seeks to live out the Sermon on the Mount including the principle of nonviolence. He contracted a serious form of cancer that began in his lower spine. He decided to learn all he could and employ multiple approaches toward healing. He worked with his oncologist in planning his chemotherapy and radiation treatments. He asked people he knew who were gifted in prayer to visualize his healing. He began to practice a form of meditation in which he saw the chemotherapy chemicals as bottom-feeding catfish, slowly gobbling up the unwanted cancer cells in his bloodstream.

Hank’s cancer went into remission, and he lived another 25 years. His spine was damaged, and his walking was impaired, but his spirit was not. Even if he had not had such a good outcome, I believe he would have died with a calm mind and strong heart. He chose curiosity over fear.

The second insight comes from a book on golf:

“Dave, an instructor at a golf school, asked me for advice about his own game. He wanted to know how to ‘putt without caring.’ He said, ‘How do I not care? I do care! Otherwise I wouldn’t be out there playing golf.’ I told him his problem was with the word ‘care.’ Of course you care about making the putt. The point is not to worry about whether you will make it or not. I then asked him to pay close attention to how each of the next sentences made him feel: ‘Dave, I care about you.’…’Dave, I worry about you.’”

— Dr Joe Parent, Zen Golf: Mastering the Mental Game, 2002

We don’t have to have any interest in golf to get the point. So much of our time is spent wanting life to meet our expectations. We press, fret, strategize, and — loaded with anxiety — act. If we don’t get what we want, we blame others or ourselves.

Joe’s point is instead of worrying about an upcoming action, we focus on caring about it. That feels different. He also believes shifting our approach to caring increases our chances of being effective.

Imagine standing in front of a mirror and making an expression that conveys worry. Our brow wrinkles. Our eyes narrow. Our breathing may become shorter. We tense up. It’s a drag.

Then imagine shifting your expression to one expressing care. Our face relaxes, our eyes open. Our pulse probably slows down. It’s a nice way to be in these bodies of ours.

Would you rather have someone worry about you or care about you?

Would you rather be afraid or curious?

Spiritual traditions offer us alternatives to fear and worry.

Buddhism teaches we can live more compassionately and freely when we let go of rigid expectations. We still formulate clear intentions with whatever we are facing – including being present and compassionate with ourselves and others – but that is different from giving into anxiety.

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus says, “Therefore do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about itself. Each day has enough trouble of its own.” As an adult who’s personally and economically responsible for myself and others, I need to be vigilant, informed, and careful as I manage our resources and plan for the future. But I try to do so from a place of caring, not worry.

In 1999 I visited the “Tomb of the Patriarchs” mosque in Hebron, Israel. I remember seeing two people. One man was sitting on the floor with his back to a wall, reading. Another was lying on the floor taking a nap. While there was tension at the security checkpoints we passed through on our way there, the mood inside the mosque was spacious and peaceful.

When we are in challenging situations, we may want to observe how we are approaching them. Are we being driven by fear or curiosity? And do we want to be filled with worry, or instead, focus on simply caring for ourselves and others?

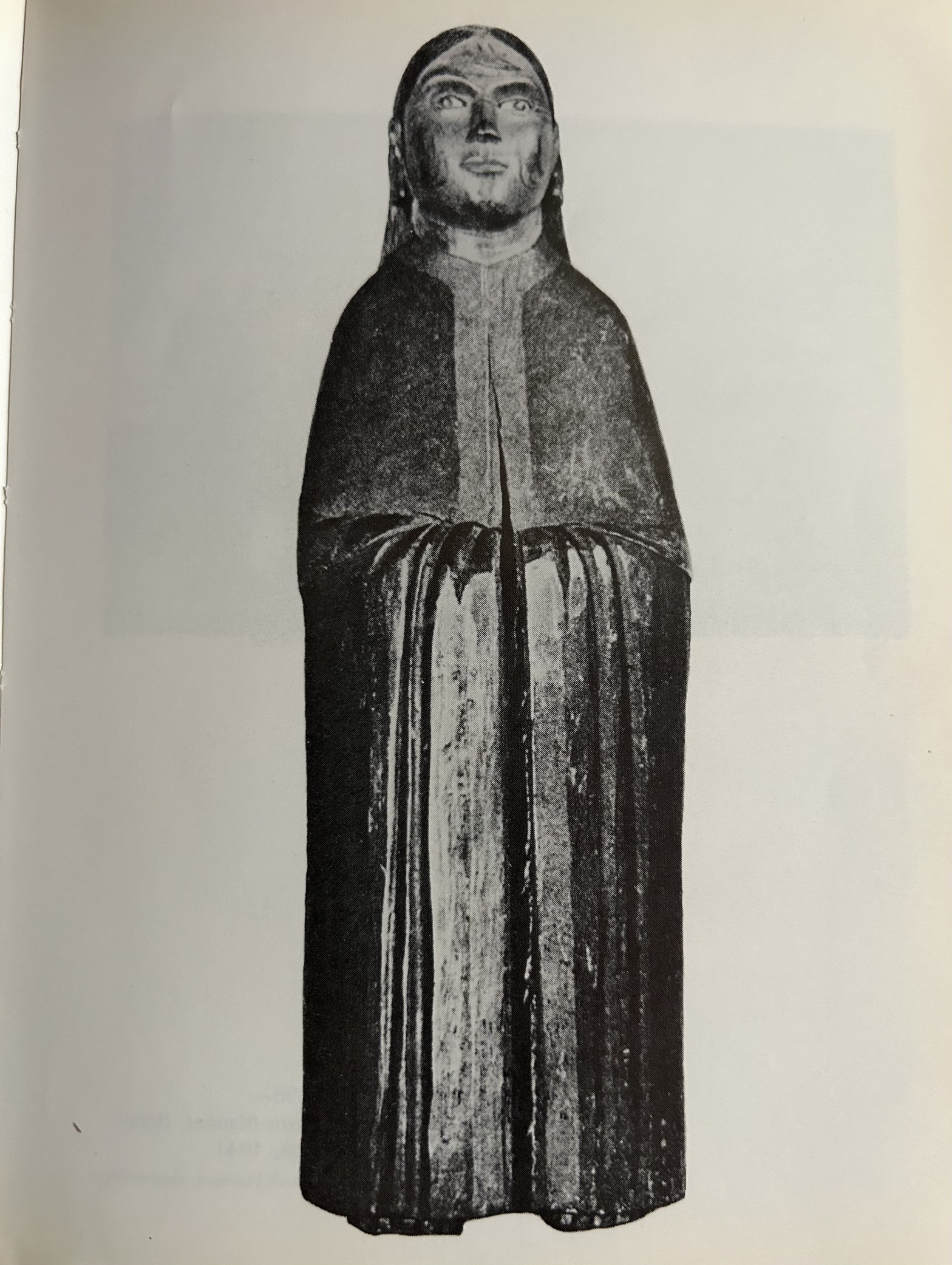

Image:

“Feeling Light Within, I Walk,” Navajo Night Chant/Native American sculpture, Vancouver, The Quiet Eye: A Way of Looking at Pictures

Note: in a prior post, I shared a similar reflection drawn from training sessions I used to lead, and included some points from a grief counselor about how “companioning” can be a distinct form of caring: “Is Your Intention to Cure or to Care?”