On June 27, I was preparing to be discharged from the hospital after a five-day stay for a strep infection in my cervical spine. Just before noon, a nurse specialist came to my room to insert a PICC line, the conduit for the daily injections I would need the next 6-8 weeks.

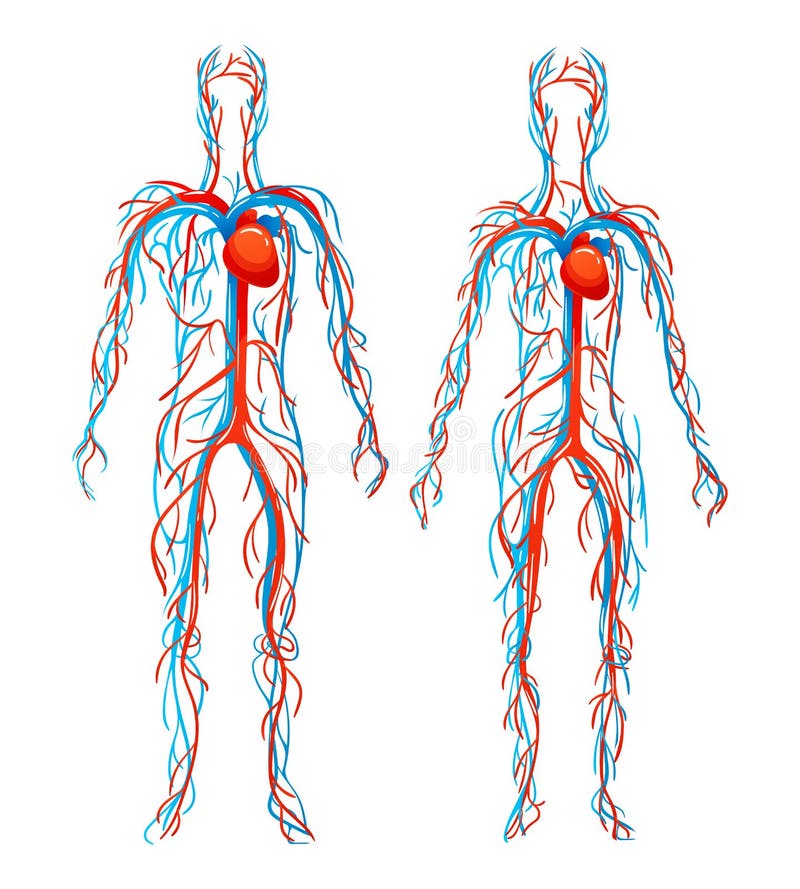

She began by creating a sterile environment around me. Then, in a 40-minute procedure, she inserted a tiny tube into a vein on the inside of my arm just above my right elbow; using an ultrasound scope to navigate, she threaded it up my arm, across my chest, and to the point above my heart where the medicine would enter my blood stream. She covered the area around the entry point with a special dressing that a visiting nurse would change every week. The exposed end of the line consisted of two purple, white and blue plastic insertion receptacles (“lumens”) where the syringes would be attached each morning; these dangled from my forearm when not covered.

The PICC line remained in my body throughout the summer. Every morning it transported saline solution, heparin, and the medicine.

On August 22 (57 days later) I met with the infectious disease specialist. She told me that the strep infection that had tried to make my cervical spine its summer home had fled the premises; the treatment had succeeded and it was time to remove the PICC line. I thanked the doctor for her care.

The nurse came in for the removal. I asked my wife to video the process. With minimal preparation, the nurse began pulling the line out. I expected it to be a bit messy – won’t there be some blood or fluid? But it came out clean and dry. I expected to feel some sensation, but didn’t feel a thing. The procedure took about 20 seconds. Just as a fisherman records the size of a trout, the nurse measured it: 43 centimeters (17 inches). I asked her if I could keep it. She wrapped it in a sterile glove and gave it to me. I took it home with me like a party favor. Here it is:

For medical professionals, inserting and removing a PICC line is a routine procedure, as are many other life-giving practices like placing stints, shunts, pacemakers and artificial joints. But to those of us who benefit from these devices, the experience can seem like a miracle.

In the last week I have been contemplating my PICC line as I would a work of art. It continues to fascinate me: “This little stretch of tubing helped save my life.”

In a sense, it is a work of art. Somebody had a vision, then probably experimented with different materials, shapes, textures and colors. They narrowed it down to what could be manufactured, marketed and used. Somebody (perhaps a government agency or university) funded the process. And now it’s out there in the world, saving lives with simplicity and elegance.

For me the PICC line was literally a lifeline. And it’s led me to think about other “lifelines.”

Years ago I participated in a drum circle. At one point the leader had us place our two fingers on the right side of our neck so we could feel our carotid artery pulsing. He began echoing the steady beat with his drum and invited us to do the same. He reminded us that this artery formed while we were in the womb, picking up the rhythm of our mother’s heartbeat to give us life. He encouraged us to realize this is an uninterrupted pulse going back in time, passing from one generation to the next, reaching to our most distant biological past. It is a lifeline that connects us with all that breathes.

I see the people who helped me heal as part of my lifeline: the doctors, nurses and technicians who used their knowledge and skill to serve me. And my wife was my lifeline. Morning after morning throughout the summer she carefully followed the 25 minute procedure to give me the injections.

We rely on many lifelines to live out our days. I am thankful for them all.